Early in 338, Artaxerxes III Ochus, son and successor of Artaxerxes II, was poisoned by his Chiliarch, Bagoas. Greek and Roman writers were fond of depicting eunuchs as scheming half-men, flabby and beardless, and restricted to concocting mischief in the women’s quarters. The physical description may be close to the truth: such figures appear on Assyrian reliefs and have been identified as eunuchs. But the influence of some eunuchs was not confined to the harem. Like the Byzantine Narses, Bagoas was a powerful individual at court and a competent military man. He engineered the accession of Ochus’ son, Arses, who reigned briefly as Artaxerxes IV, but eliminated the king’s brothers and then Arses himself. He miscalculated, however, when he assumed that he could set up Artasata (Darius III), whom Greek writers called Codomannus, as his puppet. Darius III, although the Alexander historians portrayed him as a coward, was an experienced warrior, who had defeated an enemy champion in the Cadusian campaign of Artaxerxes III; at the time of his accession he was forty-four or forty-five years old and wise to the eunuch’s machinations. Suspecting treachery, he forced Bagoas to drink his own poison.

Intrigues at the court, especially those resulting in a change of ruler, are generally accompanied by uprisings in the provinces; for the peripheral regions are encouraged by the perceived weakness of the central government. The Egyptians, only recently reintegrated into the empire, were induced once again to rebel, this time by a certain Chababash, whose name suggests he was not a native Egyptian. The dates of Chababash’s rule have been much debated, though it is certain from an inscription on a sarcophagus lid of an Apis bull that his reign extended into a second year. Since Isocrates speaks of stability within the Persian Empire in 339 and we know that at Issus in late 333 Egyptian troops served under the satrap Sauaces, it is most likely that the Chababash interlude in Egypt followed the intrigues of Bagoas, which put Arses (Artaxerxes IV) on the Persian throne. This period coincided with Philip’s decisive victory at Chaeronea, the formation of the League of Corinth, and the organization of the Panhellenic war against Persia. If the Egyptian rebellion was triggered by the weakness of Arses, it was almost certainly suppressed by the new king Darius III in 336.

In the spring of 336, Philip had sent an advance force of 10,000 Macedonians to AsiaMinor under the command of Parmenion, Attalus, and a certain Amyntas, perhaps the son of Arrhabaeus. Their presence, and the apparent initiation of the war against Persia, induced the Carian satrap Pixodarus to seek an alliance with Philip II, in the expectation of Macedonian success, at least on the coast of Asia Minor. But, by the fall of 336, Philip had been assassinated, Egypt recovered for Persia, and Pixodarus had found a new son-in-law in Orontopates. Indeed, the latter’s position as satrap of Caria suggests that Darius did not trust Pixodarus entirely. For the Macedonians, a window of opportunity had opened and closed. Whether Darius had sent gold to Macedonia to secure Philip’s assassination is unclear: Alexander found it convenient to level the charge against his opponent in 332, knowing that many in his camp and in the Greek world would regard it as plausible, if not dead certain.

Should Darius have taken measures to preempt Alexander’s invasion? Was he capable of doing so? These are difficult questions to answer. On the one hand, he may have found it difficult to secure a new fleet capable of contesting the crossing of the Hellespont. On the other, he may not have thought it necessary. Perhaps he was encouraged by the poor showing of the advance force, which Memnon had managed to hold in check, and by the reassertion of the pro-Persian element in cities such as Ephesus when the news of Philip’s death became known. News of rebellions in Europe must also have provided grounds for optimism. Certainly, Darius had little reason to assume that the untried Alexander would have much more success than Agesilaus had some sixty years earlier, and he must have believed that the armies of a coalition of satraps from Asia Minor would suffice to repel the invader.

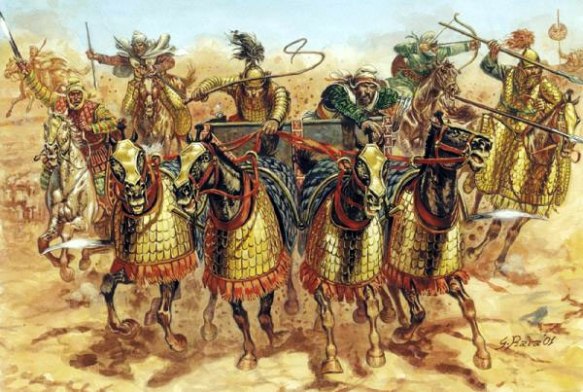

It is a common mistake to assume, from hindsight, that Alexander’s conquest of Persia was inevitable or that the satraps and their king must have viewed the Macedonian invasion with deep foreboding. The Persians had learned the value of Greek hoplites, and they had a plentiful supply of them – though as it turned out they were reluctant to use them to maximum effect. Their skilled horsemen by far outnumbered the invader’s cavalry. Only too late would they discover that their own cavalry, armed with javelins and bows, were no match for the “shock tactics” of the dense wedges of Macedonians and Thessalians. But all that was yet to come, with neither side sufficiently experienced in the techniques and weaponry of their opponents.