9th Lancers on the march to Kandahar, water-colour by Orlando Norie. The troops would march in the early morning to avoid the full heat of the sun, halting a few minutes every hour. In this way, the column managed to cover up to 20 miles a day.

Kandahar: 92nd Highlanders storming Gundi Mulla Sahibdad. Oil by Richard Caton Woodville.

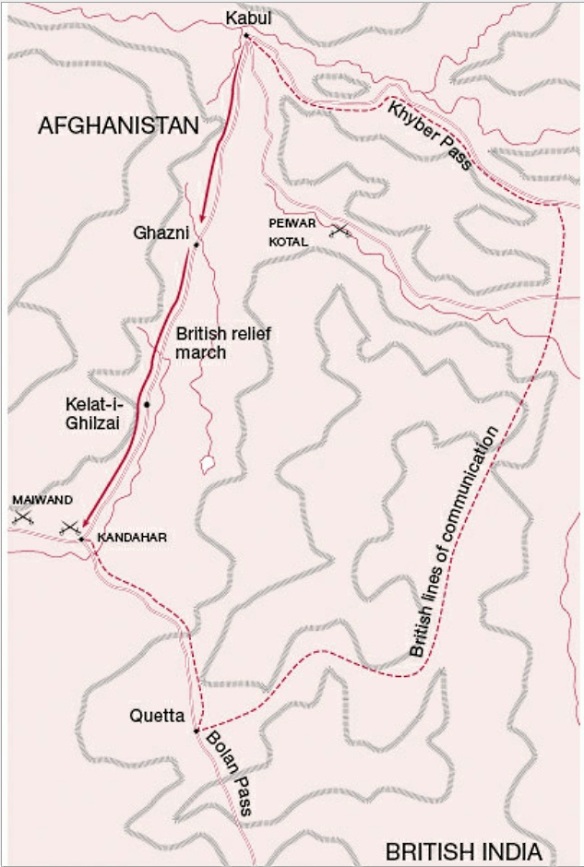

The defeat of a small brigade at Maiwand and the siege of Kandahar prompted a gruelling relief march by General Roberts. On arrival, they flew straight into battle and defeated the Afghans under Ayub Khan.

The Amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali Khan, faced an impossible dilemma. On opposite sides of his troublesome realm lay the Russian and British empires, which were rivals in trade, in the establishment of colonies and influence in Asia. Britain regarded Afghanistan as a buffer state between the sprawling Russian dominions of central Asia and its own possessions in India, and viewed any interference with Afghanistan as the prelude to a Russian thrust towards the subcontinent. To counter that threat, Britain deployed agents and consuls, made strong signals to Tsar Alexander of Russia and, where necessary, deployed military forces to reinforce its claims. The Russians were aware that, despite the size of their empire and its vast reserves of manpower, they were financially weak and constantly threatened with internal unrest, perhaps even revolution. They regarded it as essential to maintain the prestige of the Tsar and to put pressure on foreign rivals with a show of force whenever the empire seemed to be threatened.

From 1877 to 1878, Russia was embroiled in a war with the Ottoman Turks and the campaign in the Balkans had been protracted. When the Russians had finally broken through the Turkish defences at Plevna in Bulgaria, and seemed poised to capture Constantinople, Britain dispatched a fleet to the Dardanelles, assembled a force of domestic and Indian troops at Malta and threatened war in response. In the Russian capital, the Ministry of War believed the only way to counterbalance the British threat was to send an army through the wastes of central Asia, promising the Afghans plunder from the plains of India. Colonel Nikolai Stoletov was sent ahead of the army to start a diplomatic offensive to ensure the safe passage of the Russian force.

British agents alerted the government of India – under the viceroyalty of Lord Lytton – to the Russian envoy, and the British rulers in Calcutta demanded that the Afghans receive a diplomatic mission to maintain their interests and to counteract the Russian move. Although the British had no knowledge that a tsarist army was approaching, Lytton was suspicious about both the Russian and Afghan motives, particularly when his demands for a mission were turned down by the Amir. Lytton sent an ultimatum, but still the Afghans refused to negotiate. If the Amir felt that hosting the Russian envoy meant that he would enjoy the backing of the Tsar’s soldiers when they arrived, he was to be bitterly disappointed: Britain and Russia managed to avert a war in the Balkans, and the Russians abandoned their march towards India. Just as Stoletov’s mission withdrew, the British ultimatum expired and the fortress of Ali Masjid at the head of the Khyber Pass was captured by British and Indian troops.

The regular Afghan army was in no position to defeat the British, and after a couple of engagements, the most serious at Peiwar Kotal, the way to Kabul was open. Sher Ali had fled and died north of the Hindu Kush, and his son, Yakub Khan, was in no mood to fight the British. In May 1879, the new Amir was compelled to sign a treaty at Gandamak that gave the British control of his foreign affairs and forced him to accept a permanent British resident in the capital. The war appeared to be over and the British troops withdrew. Within weeks, however, the new Residency had been attacked by mobs of mutinous Afghan soldiers. Stationed there was a small detachment of the elite Corps of Guides, led by Major Sir Louis Cavagnari (the British Resident in Kabul) and Lieutenant W. R. P. Hamilton. They refused to surrender and fought on without hope of relief. The Residency was set alight, and part of the building had to be abandoned. The Afghan assailants were also able to use the cover of narrow streets and neighbouring buildings to get close to the windows. Eventually, the defenders had to fight from the first floor. To clear the approaches and to neutralize a cannon that had been brought up to blast the walls, Hamilton and 25 others made three charges out of the building, each one clearing the street only temporarily. With the British officers dead or dying, the Afghans appealed to the Muslim soldiers still alive inside to surrender, but the Guides refused to betray their regiment. A fourth sortie was made but its success was again short-lived. The gates were forced, the fire caused part of the building to collapse and the Afghans rushed in. The remaining troops fought to the last man – with Hamilton’s actions earning him the first posthumously awarded Victoria Cross – but they were all cut down. Their bodies were mutilated, and their remains tossed onto the city’s rubbish heap while the ruins of the Residency were looted for anything of value.

When Major General Sir Frederick Roberts, the commander of the Kabul Field Force, heard of the massacre, he immediately halted the withdrawal that was underway and force-marched his way back to Kabul with 6,500 men. Amir Yakub Khan, afraid of the city mobs, was offered protection by Lord Roberts, but the reluctant leader quickly abdicated, saying he would ‘rather be a grass-cutter in India’ than remain on the throne in Afghanistan. Roberts therefore found himself the de facto governor of the country, and, while the government in India wondered who could replace the Amir, Roberts tried to establish who had been responsible for the massacre of the British Resident and his escort. A number of former Afghan soldiers were captured and Roberts organized a military tribunal, which sentenced the ringleaders to be executed by hanging. At the same time he was careful to win over the people of Kabul by ensuring public order and opening a health clinic. For some weeks these measures proved successful, but the Afghans were concerned that the British might intend to stay as permanent occupiers. As the autumn drew on, individual tribes clashed with British outposts. Gradually the resistance strengthened, and by December a large coordinated insurgency had evolved. Tribal leaders tried to concentrate their vast numbers of irregular fighters on the capital, and the number of skirmishes increased dramatically. Eventually, tens of thousands of fighters occupied the hills around the capital. Roberts withdrew his garrison into an entrenched camp at Sherpur to await the onslaught.

The Afghans’ attack began on 15 December, and lasted several days, gradually closing in around the British cantonment. Preparations were made for a final night assault on 23 December that would overrun the foreign infidels and result in a massacre of the garrison. Mullahs inculcated a militant religious fervour and the fighters encouraged each other. As the hour of the attack approached, scaling ladders were assembled and the great mass of tribesmen crunched softly through the snow towards the walls. But Roberts had received intelligence warning him of the precise hour of the attack. His men were stood to arms, field guns loaded and bayonets fixed. Although his forces were stretched thin by the length of the perimeter, a few star shells lit up the advancing Afghans and allowed Roberts to concentrate and direct his firepower. As the first explosions burst among them, the Afghans drew their long knives, fired their rifles and muskets wildly at the walls, and then broke into a run. The British and Indian troops waited until the Afghans presented the best possible target, then opened fire. Breech-loaders could be aimed and shot several times a minute, and with the order ‘rapid fire’, up to 15 aimed shots could be unleashed by each rifleman. The effect was devastating, and by 1300 hours the following day the Afghan attack had been smashed. As the tribesmen tried to escape they were set upon by cavalry armed with lances and swords, adding further casualties to the toll. The revolt at Kabul had been broken up and once again the country seemed secure.

Away to the south, however, the situation was soon rather different. On 27 July 1880, Major-General James Primrose, the commander at Kandahar, had sent a brigade out to Maiwand to locate and destroy an Afghan army reportedly led by a new pretender to the throne, Ayub Khan. The combined British and Indian field force numbered 2,476 but its reconnaissance failed to locate any enemy forces. Turning to the north, they suddenly found themselves confronted by Ayub Khan’s army in a great semicircular arc and were subjected to a fierce cannonade. Lingering on the flanks of the Afghan host were thousands of tribesmen who began to edge their way around the hastily formed British army firing line. Broken terrain offered the Afghans considerable cover, and after some hours – and very heavy losses – the Indian troops on the left of the British line were in danger of envelopment. The Afghans then sprang their main attack, engulfing the smaller British force. Small knots of men tried to stem the tide, and the 66th formed a ragged square to fight it out to the last man. In a matter of hours, 934 British and Indian soldiers lay dead, and a further 175 were missing. Wounded men were butchered, and any isolated parties trying to carry away their injured colleagues were likewise surrounded and cut down. Fugitives trickled back into Kandahar but the 4,000-strong garrison was depleted and demoralized by the defeat at Maiwand and seriously outgunned and outnumbered. During the early part of August Ayub Khan moved his army to within range of the city and decided to lay siege.

Roberts was given command of a flying column that would march to the relief of Kandahar as soon as possible. He set out on 9 August 1880, reasoning that the Kandahar garrison could not wait until more British forces came up from India through the Bolan Pass. Roberts would have to cut himself from the supply routes that ran from Kabul to reach the beleaguered force in time. The route to Kandahar meant a march of over 90 miles (145 km) through some inhospitable terrain. Moreover, the broken ground forced Roberts to leave his field guns behind and take only light mountain artillery. To add to the challenge, the march would have to take place at the hottest time of the year, and it was likely that swarms of tribesmen would harass the column. Orders were issued that no man was to be left behind, and vigilance in security was to be strictly maintained. Despite this, the 9,986 fighting men, 8,000 followers and 10,000 transport animals (including ponies, mules and camels) were strung out for five miles, even where the terrain permitted a fairly cohesive formation. Roberts therefore organized his force in three brigades, each part able to support the other. Cavalry were thrown out front and rear and on either flank to act as a screen for the main force, but their patrol pattern meant that they daily had to march and ride greater distances than the main body of the column, adding to their fatigue.

Roberts had been meticulous in his planning and provisioning. Private Samuel Crompton of the 9th Lancers recalled that ‘So perfect was the foresight of our chief that, when at last we got to Kandahar, we had three days’ supplies in hand.’ Crompton also remarked on the sights and sounds of ‘grumbling camels, the stubborn donkeys, the wild little native ponies and the patient, plodding horses’ and the disconcerting knowledge that they were a ‘lost army’ – in the sense they were completely cut off from the world. At first they managed 11.5 miles (17 km) a day and then, as the country grew rougher, they ‘settled down to the hard, stern graft of it’.

When it came to dealing with the Afghans to obtain supplies, Roberts insisted on strict discipline. There was no looting, even where locals exhibited hostility. Particular care was taken not to offend women, lest it infuriate the local men. Everything was paid for in advance, including the 5,000 sheep purchased outside Kabul and corn bought from farmers along the route. Water and firewood were the most scarce resources, and so Roberts decided to purchase a few houses en route and had them stripped out for firewood. Water, however, while it could sometimes be located in villages or dug from seemingly dry beds, was often brackish.

The column was roused every morning at 0300, and set off an hour later. A conventional routine of ten minutes halt every hour was maintained throughout the day, with some longer rests in which meals were prepared. For the sake of security the marchers halted before 1900 hours each night, selecting positions they felt able to hold. The intense cold of the nights made sleep a rarity, while the dust raised by the march tormented every participant. It choked every throat, clogged everything and clung to the sweaty skin of each soldier. The camp followers proved to be the weak link in the whole expedition. Footsore or disheartened by the forced march, some began to lag behind despite the entreaties of the rest of the column. Crompton noted that even when threatened they would ask to be left to die. Others would deliberately slip away from the column at night and hide. Any deserters found by the Afghans were always murdered, as tribesmen believed that the skill of British surgeons meant wounded men would recover and return to take their revenge. They also believed that, if mutilated, these infidels would never enter paradise.

Roberts ensured that the Afghan garrison of Ghazni gave his force supplies, but soon after leaving the city, a number of observers noted that the Afghans had dug up a nearby cemetery where the fallen of the First Afghan War were buried. The Afghans had renamed the local settlement ‘the resting place of martyrs’ to commemorate their own dead, but had scattered the bones of British and Indian troops around on the surface. It was a stark and grisly reminder of the fate that would befall the column if they failed in this epic march.

At Kelat-i-Ghilzai (Qalat), Roberts collected the small British outpost force and learnt that Kandahar was still besieged. He also discovered that a sortie had been made, but that a number of casualties had been sustained. The garrison was nevertheless still intact and holding out. Roberts therefore ordered a day-long halt to allow his force to get some much-needed rest. The incidence of disease and heat injury had fortunately remained low and, despite everyone’s fears, no cholera outbreaks had occurred. Roberts himself was ill after leaving Kelat, suffering a liver complaint, dyspepsia, headaches, chest pains and a loss of appetite. Feverish, he was unable to ride and had to be carried in a dhoolie (covered stretcher), but maintained his drive and made constant enquiries as to the welfare of the troops. This concern was reflected in the nicknames he earned from them: he was known affectionately as ‘Bobs Bahadur’ or ‘Fighting Bobs’.

On 25 August, Roberts received more intelligence from Kandahar. It seemed that news of his approach had caused the Afghans to pull back from the immediate vicinity of Kandahar, and occupy a position around the Arghandab River. The move meant he had to be on guard in case the Afghan force decided to try and intercept him while he was strung out on the march, particularly as he possessed little artillery with which to fight a long-range action. The interception was not attempted, and his force soon reached Kandahar itself, where the anxious garrison cheered the relief column with enthusiasm. Roberts dragged himself back onto his horse to make the arrangements to re-establish a line of communication to India, and to start locating the enemy in order to make an immediate attack. Equipped with the garrison’s 15 field guns, Roberts could take the offensive with confidence. His only grumbles were that those besieged in the citadel had exhibited little offensive spirit and had ‘never even hoisted the Union Jack until the relieving force was close at hand’.

On 1 September, the day after the march had reached Kandahar, Roberts launched his men against the Afghan positions. Ayub Khan made a rapid escape and abandoned all of his artillery, and many of the tribesmen had already melted away to tend to their harvests. The remainder fought it out for as long as they could, losing more than 600 lives in the process. Highlanders and Gurkhas made a direct assault on the Afghan entrenchments with complete success. Roberts’ losses were just 40 killed and 210 wounded.

What particularly pleased Roberts about the victory was the recovery of two British field guns lost at Maiwand, as well as a store of other guns and trophies. Yet he felt his crowning achievement was to have restored British military prestige after Maiwand. He believed this psychological achievement – for both the population of the region and at home – outweighed even the march from Kabul to Kandahar, which had been a true feat of endurance.

The political consequences of the war were rather mixed. Afghanistan returned to its status as a buffer state and the British found a suitably compliant ruler in the form of Amir Abdur Rahman. The Residency at Kabul was not rebuilt, and the British continued to rely on secret agents to keep abreast of intrigues in Afghanistan during the Great Game, though no attempt was made by Russia to reestablish influence in the country until long after the British had quit India in the 1940s. The march from Kabul to Kandahar remained a celebrated event in Britain. The actions of Roberts had captured the essence of every relief march in aid of those beleaguered by assailants: the race against time, the endurance of the soldiers, the tough environment and the threats of sudden attack along the line of march by overwhelming numbers. Lord Roberts’ force had come through all the challenges and fought a decisive battle right off the line of march. It was a brilliant success against the odds.