The victory of Sadowa made General von Moltke a celebrity, though an unlikely one. Intellectual, thin, clean-shaven, crisp and dry in speech and writing, he had the air more of an ascetic than a warrior. Although a gifted translator, he was so taciturn that the joke went that he could be silent in seven different languages. In 1867 he accompanied the king to the Paris Exhibition, was presented with the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, and had conversations with French marshals Niel and Canrobert. The social niceties over, he returned to his office in Berlin to devote his thought to the problems of waging war against France. As professional military men, both he and Niel privately believed that a war between France and the North German Confederation was inevitable. As Niel once put it, the two countries were not so much at peace as in a state of armistice.

It was Moltke’s job, as it was Niel’s, to ensure that his country was ready when the test came, and he went about his task diligently. As a conservative Prussian, he saw France as the principal source of the dangerous infections of democracy, radicalism and anarchy. As a German, he shared the nationalist belief that Germany could become secure only by neutralizing the French threat once and for all.

Following the war of 1866, the Prussian army became the core of the Army of the North German Confederation. Under War Minister Roon’s direction, integration of the contingents of the annexed states into the Prussian military system proceeded without delay. As Prussian units were regionally based, other states’ forces were readily accommodated into the order of battle while respecting state loyalties. Thus troops from Schleswig-Holstein became IX Corps of the Confederation Army, those of Hanover X Corps, those of Hesse, Nassau and Frankfurt XI Corps and the forces of Saxony XII Corps. In addition to the manpower provided by this regional expansion, the new army could call upon the enlarged pool of trained reserves produced by Roon’s earlier reforms. While maintaining an active army of 312,000 men in 1867, the Confederation could call on 500,000 more fully trained reservists on mobilization, plus the Landwehr for home defence. Once the southern states’ forces were included following the signing of military alliances, the numbers available swelled still further. By 1870 Germany would be able to mobilize over a million men.

The world had hardly seen such a large and well-disciplined force. Its backbone was the Prussian army, combat-hardened and commanded by experienced leaders, which had won the 1866 campaign. The post-war period allowed time to make promotions, weed out unsuitable commanders, and learn lessons of what could have been done better. The time was well used.

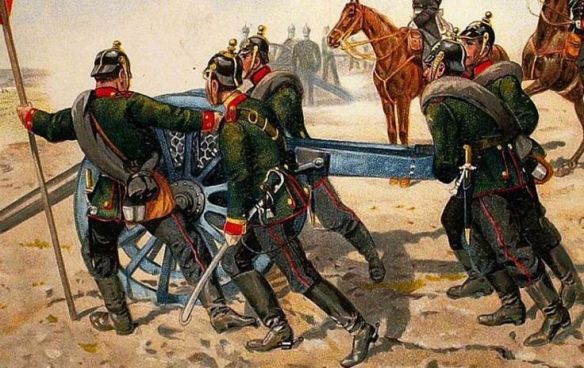

For instance, Prussian artillery had not performed as effectively as hoped against the Austrians for several reasons: faulty deployment, lack of coordination with other arms, technical failures, and want of tactical experience in handling a mixture of muzzle-loading smoothbores and the new breech-loading steel rifled cannons. All these deficiencies were addressed. At the king’s insistence, Krupp’s steel breech-loaders became standard, this time with Krupp’s own more reliable breech blocks. From 1867 General von Hindersin required gunners to train hard at a practice range in Berlin until firing rapidly and accurately at distant targets became second nature. Batteries also practised rushing forward together in mass, even ahead of their infantry, to bring enemy infantry quickly under converging fire. Time and again, this would prove a devastating tactic. If the Battle of Waterloo proverbially was won on the playing fields of Eton, it is small exaggeration to say that Sedan was won on Germany’s artillery ranges. The proficiency of German gunnery was to astound the French in 1870.

Less spectacular but equally important in conserving the lives of German troops were improvements to the medical service. The huge numbers of wounded after Sadowa had swamped the medical services. Disease and infection had spread rapidly in overcrowded field hospitals. In 1867 the best civilian and military doctors were called to Berlin, and their recommendations for reform were implemented over the next two years. The medical service was put in charge of a Surgeon General and army doctors were given enhanced authority and rank. Sanitary arrangements for the health of troops in the field were revised and their enforcement became part of the regular duties of troop commanders, who were also issued with pamphlets explaining their responsibilities under the 1864 Geneva Convention. Troops were issued with individual field-dressings to staunch bleeding. Medical units were created and all their personnel issued with Red Cross armbands. The units included stretcher-bearers trained in first aid who would be responsible for evacuating the wounded from the front to field hospitals. From there evacuation to base hospitals would be by rail using specially fitted out hospital trains. Once back in Germany, where the new Red Cross movement was taken very seriously, the wounded would be cared for with the help of civilian doctors assisted by volunteer nurses recruited and trained under the active patronage of Queen Augusta. Yet there would be no conflict of authorities in wartime, nor any room for civilian volunteers wandering about the combat zone under their own devices. The work of civilian doctors and nurses would be directed by a central military authority in Berlin. Like the artillery, the medical service was transformed between 1866 and 1870 by a systematic approach to overcoming the problems experienced in modern war.

This approach was epitomized by the General Staff itself under Moltke’s direction. In 1866 the General Staff had established itself as the controlling brain of the army and had won confidence by its success. It recruited only the very best graduates from the Army War College, and had expanded to over one hundred officers, who were assigned either to specialist sections or to field commands. Its task was to ensure that the army in wartime operated like a well-oiled machine to a common plan. It worked effectively because it was well integrated with the command chain and avoided unnecessary centralization. Army corps were responsible for carrying out their part of the plan. The commander of every major unit had a chief of staff who was in effect Moltke’s representative. Many senior commanders had themselves done staff duties, just as General Staff officers were required periodically to move to operational duties so that they understood the problems of field commanders. Germany’s 15,000 officers were expected to show initiative in achieving objectives laid out in a general plan, and to understand their duty to support other units in pursuit of it. Moltke organized regular staff rides and war games to provide his officers with experience in solving command problems, together with related skills like map reading in the field. Intelligence on French forces and plans was continuously gathered and updated.

Between 1867 and 1870 Moltke continually revised plans for the rapid mobilization of German forces and their deployment on the French frontier. The expansion of the railway network, the increasing number of double-track lines, and continual refinements in planning enabled him to cut down the time needed for this operation from over four weeks in 1867 to just three weeks by 1870. Six main lines would carry North German troops to the western frontier, while three lines were available to the forces of the southern states. Every unit had detailed instructions and a precise timetable for moving from its depot to its destination and had practised embarkation. Arrangements were made for the provision of meals at fixed points along the route. However, efforts to improve arrangements for running supply trains behind the troops to avoid the problems of 1866 met with limited success, as events were to prove.

From 1868 Moltke’s planning moved beyond how to cope with a possible French invasion of Germany to envisage an invasion of France. He would use three armies, plus one in reserve, to enter Lorraine and Alsace, where the French might be expected to gather their forces around the fortresses of Metz and Strasbourg respectively. Once across the frontier, he would seek to find and engage the French main force with his largest, centrally positioned force (Second Army) while bringing his right and left wings around to envelop the enemy. In this first phase he expected to be able to bring over 330,000 men into action against an estimated 250,000 French. He provided for the possibility of having to deploy an additional 100,000 men to face the Austrians in the south and the Danes in the north, as both might be expected to join in a war of revenge. These potential threats made it imperative to beat the French as quickly as possible. Such a war on several fronts had to be provided for, even though in early 1868 the Russians promised that in the event of a Franco-German war they would mobilize along their frontier with Austria to deter that power – Russia’s rival in the Balkans – from intervening against Prussia. In either case, but particularly if France remained isolated, Moltke was confident that speed and mass were on his side, and that his strategic offensive could beat the French on their own ground. For all the care that went into his planning, flexibility was its essence. His memorandum to the General Staff of 6 May 1870 stated: ‘The operations against France will consist simply in our advancing in as dense formation as possible for a few marches on French soil till we meet the French army and then fight a battle. The general direction of this advance is towards Paris, because in that direction we are most certain to hit the mark we are aiming at, the enemy’s army.