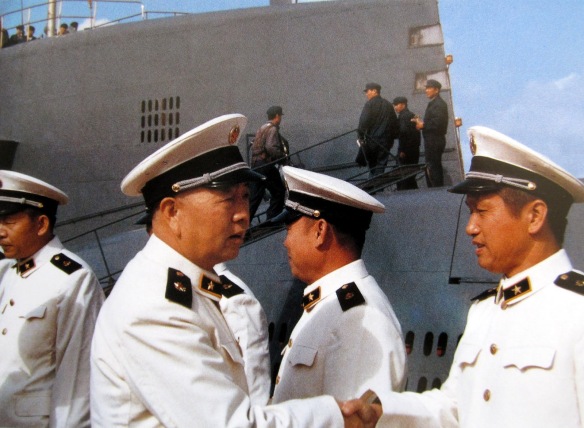

Admiral Liu Huaqing is the principal architect of the rapid expansion of the Chinese navy’s presence in the western Pacific. He believed that by 2040 the nation should have an active blue-water force in the region, with several aircraft carriers at its disposal.

Liu Huaqing’s view of his navy’s future role came about in the early 1980s, after the sudden realization that the Soviet Union, an entity soon to disintegrate, no longer posed a consequential threat to China’s future. The Chinese armed forces (all formally known under the rubric of the People’s Liberation Army, but with the “Navy” and “Air Force” elements appended to the title) could afford to change their focus, and quickly.

Hitherto the Chinese navy’s policy had been based on coastal defense: on harrying and intercepting any enemy forces that might appear in the coastal cities, and helping the army to dislodge them and drive them back to their lairs. Since this was now not likely to happen, the naval effort could well be spent in the future on offshore defense: on broadening China’s ability to defend itself in the three great seas that surround it, the South China Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea.

So a new concept was born. China’s navy, if it were provided with enough ships and with a sufficient budget commitment for the long term, could now project the boundaries of the nation’s influence outward and ever outward into the Pacific Ocean as the years went on. The concept of the First Island Chain was born during these strategy sessions: the need for China to secure the “green waters” within the Kamchatka-to-Borneo line, and to do her best to deny access to any foreign military that might wish to be there.

There were discussions of the allurements of the Second Island Chain and even of the Third Island Chain. The possibility, never before imagined, never even imaginable, that China could one day extend her blue-water power as far as Guam, maybe even as far as Hawaii, seemed suddenly within the realm of the possible.

Admiral Liu had almost overnight given China a new dream. And as the powerhouse of China’s new industrial might cranked itself under way in the late 1980s—as the factories began to hum, and the exports to thunder eastward, and the dollars and the gold began to flow at an unstoppable rate into the bank vaults of Beijing and of Shanghai and, after 1997, of the handed-back territory of Hong Kong—the revenues increased and the public funds became more generously available, and serious new defense spending became a possibility, then a necessity, then an absolute essential. In the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s shipyards, scores of new keels were laid down, scores of new vessels launched, and all the most-up-to-date war-fighting accessories and ammunitions were added in the fitting-out basins, and the coastal waters became white-waked with sea trials and gunfire tests and missile launches, and the new Chinese naval policy was formally implemented in acres of gray steel and black smoke and the flying of battle pennants. And all this has been accelerating across the western Pacific ever since.

There is a timetable, too. By 2000, Liu and Deng had seemingly agreed, phase one of the PLA Navy’s plan would see China in control of the green waters within the First Island Chain. This has not yet been achieved, but China’s influence inside the chain, from the Senkaku Islands in the north to the Spratly Islands in the south, and with the building of all the bunkers and airstrips and radar sites on atolls and skerries all across the region, is considerable, is intimidating, and is growing.

The presence of a Chinese attack submarine in the Philippine Sea in 2006 shows that phase two is now under way: China is making its presence felt within the Second Chain, in the waters between Luzon and the Marianas, between Cebu and Palau, between Borneo and Vanuatu. There is even serious talk these days in Beijing and Shanghai of a Third Island Chain, which includes the Hawaiian Islands, and of China seeking rights and freedoms there as well.

No red-blooded American admiral is going to look too kindly on an aspirant power from Asia bringing its vessels regularly into the seas around Hawaii. Yet Hawaiian waters are temptingly highlighted on Chinese naval planning maps these days—most beguilingly, on a map in the 2005 Chinese translation of the biblically regarded Influence of Sea Power upon History, by Alfred Mahan. Admiral Liu was still in service at the time (he died only in 2011), and his stamp would have been on the decision to draw the map this way, together with his advocacy of phase three of the master plan: that the Chinese exercise some good measure of control of the seas to the west of the Third Island Chain, and become a truly global navy, to boot, by the year 2049.

By the centenary, in other words, of the founding the People’s Republic, and of the founding, in August 1949, of the People’s Liberation Army. That is the key culminating moment for all current Chinese regional ambitions. By then, all that China believes to be China’s is expected to be back in China’s hands. The recent past has been rather kind to China’s ambitions for the slow and steady recouping of its territory. Manchuria is back. Port Arthur and Port Edward have come back. The British colonial outposts of Weihaiwei and Hong Kong are back; Hainan is back from the French, Macau from the Portuguese. Now all that remains is Formosa, the once Portuguese “beautiful island” lying between China and Japan, the recovery of which all know will provoke, unless great diplomatic skill is wielded by all parties, an almighty fight.

The rapid rise in Chinese defense spending ($166 billion in 2012, up 12 percent from the year before, and heading skyward) is part of the plan to help achieve all this, and to secure the seas beyond. The hardware is being amassed: the seventy-seven principal surface combatant ships China had in its 2014 navy (the U.S. Pacific Fleet had ninety-six), the sixty-seven submarines (the United States has seventy-one), the fifty-five amphibious ships (there are thirty in the U.S. Navy), and its eighty-five small fighting vessels (the United States has twenty-six) are all part of the plan. Only in one area, the possession of aircraft carriers, is Beijing well behind Washington, with the Liaoning and her strike group ranged against the ten enormous carriers fielded by the Pentagon. Yet even here the Chinese are catching up: three new carriers bought from Australia and Russia are being fitted out, and two more are being built in Shanghai. And while the Liaoning has a relatively antique “ski-slope” launching system, the new ships will have catapults, and a new carrier-suitable fighter is soon to be ready to join the fleet.

All this gives muscle to the Chinese plan, a design that has firm goals, set dates, political will, and a commitment of the money and machinery to undertake and achieve it. The American counterscheme, its current “offset strategy,” its so-called revolution in military affairs,10 certainly starts from a superior position: the U.S. Navy has an overall total of 284 ships, 3,700 aircraft, and 325,00 active-duty personnel, while the Chinese have 495 ships, 650 aircraft, and 255,000 crew members. Yet it appears to be based very much on a series of back-foot assumptions about China’s intentions, and about how to respond to them, rather than on any kind of forceful taking of the initiative, the kind of bull-by-the-horns approach of a figure such as Teddy Roosevelt. The four-year cycle of the American presidential election system hardly helps: whatever the Pentagon comes up with manages all too often to enjoy little long-term validity. Thanks to the realities of modern American politics, the playing of the long game is not the most prominent feature of many of Washington’s policies.