Kurdish Peshmerga Army during invasion of Iraq in 2003.

On the advance from northern Iraq towards Baghdad, American special forces teams and their Kurdish irregular allies came under attack at the Debecka crossroads from more numerous and better-armed Iraqi regular armoured forces. With nowhere to run, and facing imminent destruction, the Americans fought it out resolutely.

The American strategy for the invasion of Iraq was designed to make the best use of new technologies and assets to utilize their speed and firepower in order to create a deep psychological impact on the forces of Saddam Hussein. In contrast to the Gulf War of 1990–91, there would be no long preparatory air campaign prior to a ground assault. Instead there would be a simultaneous and combined land–air invasion that would emphasize the effects of the forces’ superiority in weaponry and their ability to manoeuvre. The approach was summed up in the expression ‘shock and awe’, and it was hoped that these tactics would break the enemy’s will to fight.

In the weeks preceding the attack, the Turkish government refused to allow the Western-led coalition to use their border as a springboard against Iraq. This refusal was partly a response to the American plan to use Kurdish irregulars, the Peshmerga, to augment their ground forces. The Turkish government had been plagued with Kurdish attacks for decades and had no wish to cooperate with these old adversaries. Consequently, the American invasion plan had to be modified. Instead of heavy armour arriving from the north and south in a two-pronged thrust, the main attack would come from the south, with amphibious operations along the coast. In the north, lightly equipped special forces would be deployed with close air support. Such light forces would be even more reliant on speed for their survival, and units were provided with all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) known to the troops as ‘War Pigs’ or GMVs (the latter being converted Humvees). In fact, in the campaign that followed, the troops were often dependent on converted civilian vehicles – such as Land Rovers and Toyotas – tooled up with an array of weapons and communications equipment. Luckily, the troops were used to improvisation.

The 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and the 3rd Battalion 3rd Special Forces Group (which had just returned from Afghanistan) consisted of highly mobile Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) teams who could call on various supporting assets, including resupply vehicle groups known as Advanced Operating Bases. Elements of the 173rd Airborne Brigade and 10th Mountain Division were attached and airpower was in the hands of the 123rd Special Tactics Squadron. Together the formation was known as Task Force Viking, a suitably warlike sobriquet. Only the 10th had the advantage of having operated in the area before, during the humanitarian relief mission known as Operation Provide Comfort (1991–96), so gathering information was in part dependent on local allies. The mission now was to prevent 13 Iraqi infantry and armoured divisions from reinforcing Baghdad as the main coalition thrust worked its way up from the south. While the skills and courage of the special forces teams were not in doubt, no one could predict how this new doctrine of pitting light forces against conventional divisions would turn out. In fact, it would be tested to the limit in the battle for the Debecka crossroads.

In February 2003, the special forces teams touched down at Arbil in northern Iraq thanks to the arrangements of CIA agents who had been deployed covertly the previous year. Although the landings were opposed by Iraqi anti-aircraft fire, a total of 51 ODAs were landed and they soon linked up with over 60,000 Peshmerga fighters drawn from the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. Parachute landings were also made to secure oilfields near Kirkuk.

The first mission of the special forces was not, in fact, to neutralize Iraqi conventional forces, but to raid and suppress the headquarters of the Ansar al-Islam, an organization led by, among others, the notorious Abu Musa al-Zarqawi (the individual who later went on to command the militant group al-Qaeda in Iraq and commit acts of wholesale murder and terror against Iraqis). The headquarters were located in a valley defended by over 1,000 insurgents and militant Kurdish fighters who opposed the Peshmerga. To soften up their defences, Tomahawk cruise missile strikes were first called in. Advancing into the Sargat Valley along several lines of attack, the ODAs and their Peshmerga allies were repeatedly held up by heavy machine-gun fire from bunkers and entrenched positions. The defenders were carefully winkled out with precision airstrikes, and fire from grenade launchers or the .50 calibre machine guns mounted on the special forces’ ATVs. The village of Sargat was taken, but stiffer resistance was encountered at Daramar Gorge. Here caves provided the Ansar fighters with plenty of cover from air attack, though the ODAs and Peshmerga were able to suppress the insurgent groups sufficiently to make a clean break. While some of the Ansar chose this moment to make good their escape to Iran, a few chose to fight it out to the end. Once the ODAs had gained the high ground, these remaining pockets were mopped up relatively easily. There were no American casualties, and in total the Ansar lost 300 men. Interestingly, scientific teams later discovered IED (Improvised Explosive Device) ‘factories’ as well as evidence of experimentation with ricin, a deadly poison. Whether these were being developed by the Ansar or left over from the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s is not clear.

Task Force Viking now pressed on towards Ayn Sifni, a town on the highway to Mosul. Control of this route would prevent any Iraqi counter-offensive against the strategically important cities and oilfields of the north. Air power again proved decisive, and it seemed that the Iraqi defences were broken up. Intelligence estimates calculated that only two platoons (some 60 men) remained; however, the leading ODA was met with a storm of gunfire. It soon became apparent that the Iraqis were still entrenched in battalion strength, with mortars, armour, anti-aircraft guns and artillery. For four hours, three ODAs and 300 Peshmerga engaged the Iraqi battalion using ‘fast air’ – ground attack aircraft armed with a variety of bombs and missiles – to hammer the Iraqis. After this tremendous bombardment the ODAs were able to get into Ayn Sifni, but almost immediately they were subjected to an Iraqi light infantry counter-attack, and salvos of mortar fire. Once again, the ODAs engaged with what light armaments they possessed and brought down precision airstrikes. The Iraqi attackers melted away.

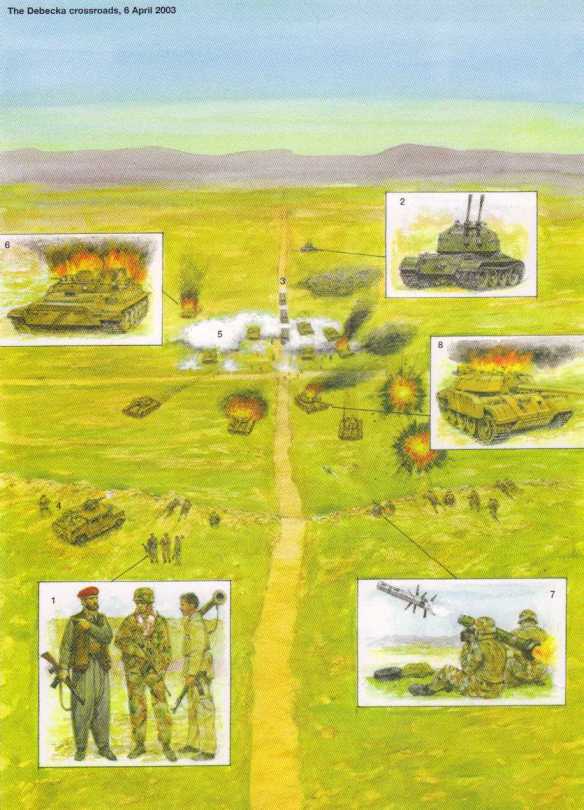

To the southeast, an even more epic action was developing at the Debecka junction. The crossroads near the village was the key to the north, as it was the point where the highways to Mosul and Kirkuk met. The Iraqis clearly understood its significance and troops (some dug in) were located around the site and on the Zurqah Ziraw Dagh Ridge that overlooked it.

Prior to the advance of the ODAs, B-52 bombers saturated the target with heavy ordnance. This achieved, ODA 044 with 150 Peshmerga drove towards Objective Rock, a junction just short of the main crossroads by the town of Debecka. ODAs 391 and 392 provided this force with fire support. To the north, 500 Peshmerga (split into two units) were tasked with the capture of the ridge. Further north still, three ODAs and 150 Peshmerga set out to take Objective Stone, a hilltop occupied by Iraqis on the flank of the coalition forces’ advance.

The Peshmerga on the ridge seized their objective against token resistance, but the battle for Objective Stone was more confused. Airstrikes had failed either to hit the targets or suppress the defenders. Two ODAs engaged, but were subjected to a withering fire from heavy machine guns and mortars. Under these circumstances, the accompanying Peshmerga refused to go forward. Calling for more air support, the two ODAs managed to extract, resupply and rejoin the fight. The remaining ODA, 043, had nevertheless managed to restart the attack themselves and together with the Peshmerga they routed the battered Iraqi defenders. Objective Stone had been captured.

As three ODAs, 044, 391 and 392, approached Objective Rock, they were confronted by a dirt berm thrown across the road, liberally scattered with mines and IEDs. The Peshmerga stopped to dismantle the obstacle, while the ODAs attempted to bypass it. As they crested a low ridge, they came under the effective fire (that is, with rounds falling among them) of Iraqi infantry dug in and occupying bunkers just beyond it. Too close to call in airstrikes, the ODAs simply let loose with everything they had. It didn’t take long for the Iraqi infantry to capitulate.

The Iraqi commanding officer then disclosed to the ODA that his armoured support, which had until recently been with him, had driven away to the south. Expecting a counter-attack, the teams drove back to the dirt berm barrier to effect a breach should they later need to make a rapid withdrawal. From there, they then sped on up to another ridge, known later as Press Hill, to carry out a covert observation of the route south. Seemingly clear of enemy armour, the ODAs then pushed on to the crossroads.

On the approach to the crossroads, an Iraqi mortar platoon was sighted as it withdrew to Debecka. ODA 392 set off in pursuit, but were halted by the fire of a ZSU-57-2: an armoured anti-aircraft tracked vehicle with two heavy machine guns. This fire continued to play on the ODA teams during the events that followed. ODA 391 had more luck, destroying lightly armoured vehicles with its Javelin (anti-tank guided missiles) and the .50 calibre machine gun on board.

It was at this point that the special forces teams noticed a number of Iraqi APCs coming on from the crossroads, pouring smoke from generators to create a screen for some hidden formation behind. The ODAs engaged with .50 calibres and tried to ready the Javelins, but the Command Launch Units (trigger mechanisms) take a few moments to warm up, and in those few seconds, several Iraqi T-55 tanks emerged from the smoke, firing their main 100 mm tank guns at the ODA vehicles. The special forces teams were not equipped to take on this sort of heavy armour, and the only sensible thing to do was to temporarily pull back and try to bring in air support. Their escape rendezvous point was nicknamed ‘the Alamo’, and was designated as a place for a last-ditch stand some 985 yards (900 metres) from the crossroads. The trouble was, as they sped back under Iraqi tank fire, that no air support would be available for 30 minutes. The troops were aware that by then they could all be dead, so they had no choice but to try and fight it out as best they could.

The Iraqi APCs and tanks were gradually closing on the ODAs, and the special forces men all but exhausted their supply of Javelins, launching missile after missile at the line of approaching targets. Several Iraqi vehicles were hit and destroyed, and their attack stalled. Regrouping, the Iraqi tanks changed direction, advancing obliquely using folds in the ground to conceal themselves from the Javelin barrage. Iraqi small-arms fire continued to pour into the Alamo position – so much so that it seemed time had run out for the special forces group.

Just at that moment a flight of two US Navy F14s screeched overhead, and the special forces teams tried to talk the pilots onto the first T-55. Mistaking a rusty tank hulk nearby as the target, one F14 dropped a 2,000 lb bomb, not on the Iraqis, but on the Peshmerga and the ODA support team at Objective Stone. The BBC correspondent John Simpson, who was with the unit, described vividly the effect of this error live to viewers just moments after the detonation: ‘This is just a scene from hell here. All the vehicles are on fire. There are bodies burning around me.’ Twelve Peshmerga and four ODA were killed, while one cameraman was wounded. ODA 391 pulled back to give assistance, as the other ODA teams tried to offer them covering fire and extract from the Alamo to Press Hill.

Now the ODA teams found themselves under more intense Iraqi artillery fire, and the Iraqi tanks lurking nearby tried to get a fix on their position. One T-55 lurched forward, trying to get a clear shot with its main gun, but it was blasted with a Javelin and exploded. As the Iraqi shells began to land closer in, American F/A-18 jets arrived and hunted off the remaining Iraqi tanks. The special forces team had pulled through. A day later, American Task Force 1-63 arrived with M1A1 tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles, so there was no chance of any successful Iraqi counter-attack.

The results of the Battle of Debecka were impressive. Miraculously, the 26 special forces men had survived unscathed, holding off a reinforced Iraqi armoured battalion – with its tanks, artillery and mortar teams – long enough for air support to arrive. The Iraqis had made a conventional attack, but, despite their strength, they had failed to overrun the relatively small and lightly armed force. Admittedly American air power was critical, but for over half an hour during the battle, this asset was simply not available and the special forces had survived the onslaught against the odds. Moreover, their Peshmerga allies had been dispersed among other positions, carrying out separate tasks during the mission. In any case, these Kurdish irregulars had no anti-tank weapons to stop the Iraqi armour. The special forces teams had relied on their own integral weapons, robust communications and a great deal of courage to take on such a large formation. Each ODA team had sought the best position to continue the engagement, and, professional to the last, there was no question of abandoning the mission.

Special forces and reconnaissance troops are useful but they are always vulnerable: the operation had underscored the importance of having heavy weapon support close by during any light or airborne operations. It is evident that special forces need to be able to improvise, and to have enough firepower to stave off defeat if it all goes wrong, meaning there often has to be a trade-off between mobility and capability. Yet, above all, it is the human qualities that matter.