Osama bin Laden’s fatwa to attack Americans around the world proved troubling to U.S. policymakers, but did not become of general public concern until the bombings of the two U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in August 1998 and the bombing of a U.S. Navy destroyer in Aden in 2000. While other terrorist groups were content to set off late-night bombs with no casualties, with these two operations, al Qaeda established itself as the world’s preeminent terrorist group, willing to tackle complex terrorist operations. American determination to bring the perpetrators to justice has lasted more than a decade as of this writing, with debates continuing over the venue for the trial of those detained for this and other attacks.

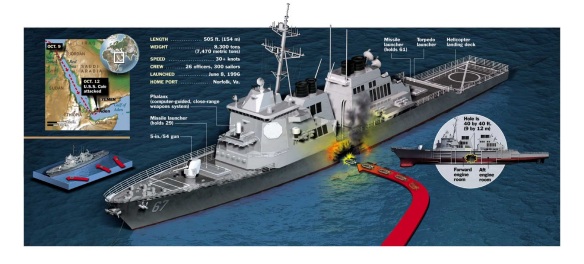

On October 12, 2000, a 20-foot Zodiac boat laden with explosives came alongside the 8,600-ton USS Cole, a 505-foot Arleigh Burkeclass guided-missile destroyer, and detonated, ripping a 40 × 40 foot hole in the hull’s half-inch-thick armored steel plates near the engine rooms and adjacent eating and living quarters, killing 17 American sailors and injuring another 44. No Yemenis were killed in the Aden port blast.

A Syrian-born cleric living in the United Kingdom, Sheikh Omar Bakri Muhammad, said that the Islamic Army of Aden (alias Aden-Abyan Islamic Army) of Yemen had claimed credit.

Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh told CNN that some detainees belonged to the Egyptian al-Jihad, whose leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, was with bin Laden in Afghanistan. Saleh said a 12-year-old boy told investigators that a bearded man with glasses gave him 2000 rials ($12) and asked him to watch a four-wheel drive vehicle parked near the port on the day of the attack. The man took a rubber boat off the top of the car and headed into the harbor, never to return. The car led investigators to a modest house in the Madinet al-Shaab suburb of Aden.

On October 16, Yemeni investigators discovered bomb-making material in an apartment used by individuals believed involved. Yemeni security said they were non-Yemeni Arabs; others said they were Saudis who stayed for six weeks in a house near Aden’s power station. Another house, close to the Aden refinery and oil storage facilities in the al-Baraiqa neighborhood, was discovered by October 21. The suspects apparently had briefly left and then reentered Yemen before the bombing. They had parked a fiberglass boat in the driveway; the boat was now missing. Police tracked the car to a house in al-Baraiqa, or Little Aden, west of Aden.

The Navy revised its theory of the bombing on October 20, saying that the destroyer had been moored for two hours and was already refueling when the bomb boat came alongside. The boat blended in with harbor workboats and was not suspected by the gun crews on the ship.

By October 24, the investigators were looking at three safe houses that served as the terrorists’ quarters in Little Aden, workshop in Madinet ash-Shaab, and lookout perch in the Tawahi neighborhood. A lease for the lookout apartment was signed by Abdullah Ahmed Khaled al-Musawah. Binoculars and Islamic publications were found in the apartment. The same name was found in a fake ID card in personal documents seized in the safe houses. Yemeni investigators detained employees of the Lajeh civil registration office in the northern farming region. Investigators looked at a possible Saudi connection—one of the individuals had a Saudi accent. Others looked at the mountainous province of Hadramaut—one suspect used a name common to the area. The press also indicated that the terrorists’ wills dedicated the attack to the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem.

On October 25, Yemeni president Saleh said that the bombing was carried out by Muslims who fought against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan and then moved to Yemen. Egyptian Islamic Jihad terrorists affiliated with bin Laden remained the key suspects; a witness identified one of the bombers as an Egyptian. Yemeni authorities arrested Islamic activists originally from Egypt, Algeria, and elsewhere, as well as local Yemenis. A local carpenter confessed that he had worked with two suspects in modifying a small boat to hold explosives and helped them to load the explosives on board. He had rented the suspects the building where they prepared the boat. A Somali woman who owned a car used by the suspects to haul the boat was questioned. Yemeni investigators believed the terrorists had given her money to buy the car.

The Taliban in Afghanistan said that bin Laden was not responsible. Osama bin Laden welcomed the attack.

Yemen arrested four men living in Aden on November 5 and 6 after tracing them via phone records that showed that they had been in contact with the suspected bombers. Officials in Lahej had provided the bombing suspects with government cars for use in Aden. The bombers knew the officials from their time together in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

On November 11, Yemeni investigators said that at least three plots against U.S. targets in Yemen had failed in the past year. Yemeni officials said a detainee claimed that terrorists had planned to bomb the U.S. destroyer USS The Sullivans during refueling in Aden on January 3, 2000. The explosives-laden small boat sank instead from the weight of the explosives.

On November 16, Yemeni prime minister Abdel-Karim Ali Iryani said that the two Yemeni bombers were veterans of the Afghan war. One was a Yemeni born in the eastern province of Hadramaut. (Osama bin Laden had Yemeni citizenship because of his father’s birth in the Hadramaut region.)

On November 19, Yemeni authorities said that they had detained “less than 10” suspected accomplices out of the more than 50 people still held for questioning.

An explosives expert reconfigured the charge using lightweight C-4 plastique. The Yemen Observer reported that the fiberglass boat was brought in from another country.

On November 21, U.S. officials said that the bombing appeared to be linked to the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Africa in 1998. A composite sketch of one of the bombers appeared to match that of a man wanted for questioning in the Africa bombings.

The State Department announced on December 7 that it supported Yemen’s decision to prosecute three and possibly six Yemeni suspects in January, following the end of the holy month of Ramadan. One of them, Fhad al-Qoso, reportedly told investigators that an associate of bin Laden gave him more than $5,000 to finance the Cole attack’s planning and video-taping of the suicide bombing. Suspect Jamal al-Badawi admitted that he was trained in bin Laden’s camps in Afghanistan and was sent with bin Laden’s forces to fight in Bosnia’s civil war. He was believed to have obtained the boat. Yemen had also identified Muhammad Omar alHarazi, a Saudi born in Yemen, as a planner of the attack and a member of al Qaeda. He may also have played a role in the truck bombings in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998.

On January 30, 2001, ABC News reported that U.S. African embassies bombing defendant Mohamed Rashed Daoud al-Owhali allegedly told the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1998 about a plan for a rocket attack on a U.S. warship in Yemen.

On February 17, 2001, Yemen detained two more suspects when they returned from Afghanistan.

Bin Laden applauded the attack on February 26, 2001, saying the Cole was a ship of injustice that sailed “to its doom.” His comments were made at a family celebration in Afghanistan and broadcast on Qatar’s satellite channel Al Jazeera. He recited a poem to celebrate the January marriage of his son, Mohammed, in Qandahar, saying “In Aden, the young man stood up for holy war and destroyed a destroyer feared by the powerful.” He said the Cole sailed on a course of “false arrogance, self-conceit, and strength.”

On March 31, 2001, Yemeni police announced the arrests of several more suspects believed to be Islamic militants. The main suspect apparently fled to Afghanistan. Ali Mohammed Omar Kurdi was arrested; his house had been searched the previous day.

Yemen arrested five suspects with ties to Islamic terrorist cells on April 14 and 15, 2001, bringing the total in custody to 28. Two jailed suspects had informed security officials about terrorist cells operating in the country. The cells had two or three members each and were directed by leaders of Yemen’s Islamic Jihad (YIJ) who were based in several countries outside Yemen, including Afghanistan. The cells assisted non-Yemeni Arabs with ties to YIJ by providing forged Yemeni passports, safe houses, and information on Yemeni security.

A 100-minute videotape made by Al-Sahab Productions (The Clouds) circulated in Kuwait City by Muslim terrorists shows bin Laden for several minutes and suggests that his followers bombed the USS Cole . His followers training at the Farouq camp in Afghanistan included them singing “We thank God for granting us victory the day we destroyed Cole in the sea.”

On October 26, 2001, Jamil Qasim Saeed Mohammed, 27, a Yemeni microbiology student and active member of al Qaeda, was handed over to U.S. authorities by Pakistani intelligence, according to Pakistani government sources. Pakistan bypassed the usual extradition and deportation procedures. He was the first suspect captured outside Yemen. He arrived in 1993 in Pakistan from Taiz, Yemen, to study microbiology at the University of Karachi. He was asked to leave in 1996 after failing to qualify for the honors program in which he had enrolled. Pakistani authorities arrested him later that year in connection with the November 1995 bombing of the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad, but he was released without being charged. He was brought to Karachi International Airport in a rented white Toyota sedan by masked members of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency, and handed over to U.S. officials who put him on a Gulfstream V jet. Government authorities detained two other Yemeni university students with ties to Mohammed.

On January 29, 2011, Yemen announced it had tracked down Mohammed Hamdi al-Ahdal and Qaed Salim Sunian al-Harithi, wanted for questioning in the case.

After a $250 million repair, the USS Cole returned to service on April 14, 2002.

On November 3, 2002, a Hellfire missile hit a car in Yemen carrying a group of al Qaeda terrorists, killing all six of them, including Abu Ali al-Harithi, a Cole suspect. Around that time, authorities captured a suspected planner of the Cole attack, al Qaeda member Abd-al-Rahim al-Nashiri, who was believed to have also planned the USS The Sullivans attack and the thwarted attack on U.S. and U.K. warships in the Strait of Gibraltar in 2002.

On April 11, 2003, 10 of the main suspects, including Jamal al-Badawi, escaped from an Aden prison.

On May 15, 2003, a federal grand jury indicted on 50 counts Jamal al-Badawi and Fahd Quso; they faced the death penalty. The indictment named as unindicted coconspirators Osama bin Laden; Saif al-Adel, head of al Qaeda’s military committee; Muhsin Musa Matwalli; A bd-al-Rahim al-Nashiri; and Tawfiq bin Attash. On July 7, 2004, a Yemeni court charged Nashiri and five other Yemenis in the bombing. On September 29, 2004, a Yemeni judge sentenced Nashiri and Badawi to death.

On February 3, 2006, 23 al Qaeda convicts, including Badawi, broke out of a Sana’a prison. Yemeni forces recaptured him on July 1, 2006. Yemen freed him on October 25, 2007. He remained on the FBI’s Most Wanted List.

On March 12, 2007, Tawfiq bin Attash told a U.S. military tribunal in Guantanamo that he organized the USS Cole attack and the 1998 U.S. African embassies bombings.

On July 25, 2007, a U.S. judge ordered Sudan to pay circa $8 million to the families of the 17 dead sailors. In mid-April 2010, another 61 grieved relatives sued Sudan for $282.5 million.

Fahd al Qoso reportedly died in an air strike in Pakistan in October 2010, although a photo of him surfaced afterward.

In April 2011, Nashiri was charged by U.S. military prosecutors with murder, terrorism, and other violations of the laws of war regarding the USS Cole attack and others.

As of late 2013, many of the accused were held in Guantanamo Bay military prison, awaiting trial.