Illyrian Warriors.

It is not always easy to guess why the Romans acted as they did, but the reason they went to war in 229 BCE genuinely seems to lie on the surface. The killing of their ambassador was an extra spur, but their primary reasons were economic. Why else help the Issaeans, with whom the Romans had no relationship? They may have been touched by their appeal, the first from a Greek state, but they acted pragmatically, not out of sentiment. Nor was it just that Italian traders had been killed; the future threat was just as potent. The Romans did not want a powerful neighbor; they wanted the Adriatic for themselves.

They came late in the season of 229, but in large numbers. Both consular armies assembled at Brundisium and crossed the Adriatic, 22,000 men transported in 200 ships. Nothing should be read into this massive force beyond the fact that the Romans had a large stretch of territory to conquer, and they had no way of knowing how strong the resistance would be. The Illyrians had been performing well in battle recently.

The consuls for 229 were Gnaeus Fulvius Centumalus and Lucius Postumius Albinus. While Fulvius led his men against Corcyra, Postumius made Apollonia the Roman base camp. Demetrius of Pharos, Teuta’s general in Corcyra, surrendered to Fulvius even as he approached, and was taken on as an adviser by the Romans for the remainder of the war. Presumably Pharos island went over with him, as well as Corcyra. With Corcyra, the Romans cut the Illyrians to the north off from their Acarnanian allies to the south, whose naval abilities had already been proved off Paxoi earlier in the year.

But it is unlikely that the Acarnanians could have made any difference. The Romans swiftly relieved the sieges of both Epidamnus and then Issa, and that was the end of the war. The Romans had easily defeated the Illyrians, who had terrorized the coastline of western Greece. Teuta, Pinnes, the royal court, and the royal treasury retreated to Rhizon, on the Bay of Kotor (in Montenegro, nowadays), a fjord with both an inner and an outer bay, each with a narrow entrance. The place was virtually impossible to assault by sea, and even more impossible by land, since the fjord ends abruptly in sheer mountains. Teuta chose her refuge well, but the Romans were content: it would be easy to keep an eye on her there. Perhaps the fact that she was confined in one of the most stunning locations in Europe was some consolation.

A number of communities in the area, whether or not they had surrendered to Rome (as Corcyra had), chose to “entrust themselves to Roman good faith.” To do this was not to make oneself entirely dependent on Rome, but it was an acknowledgment of inferior status: the people were trusting first the Roman commander in the field, and then Rome itself once the relationship had been officially ratified, to determine their fate and look after their interests. And each time a state accepted Roman protection, the Romans declared it free—that is, free to regulate itself without outside interference. There was no doubt a register in Rome of all the states which agreed to this arrangement, but otherwise it was an informal relationship, and Rome simply thought of them all as its amici, “friends.”

Fulvius returned to Italy with most of the troops, while Postumius wintered in Epidamnus to make sure the situation was secure, and to conclude negotiations with Teuta. The negotiations resulted in a formal agreement whereby Pinnes would pay whatever indemnity the Romans saw fit to impose, renounce his claim to the places that had entrusted themselves to Roman protection, and remain in his reduced kingdom, without sailing south of Lissus with more than two ships, and even then they had to be unarmed. Lissus was chosen because it was the northern neighbor of Epidamnus, and so lay on the edge of the large chunk of Illyris that had accepted the protection of Rome.

Then, leaving Demetrius of Pharos, who on his surrender had become a “friend of Rome,” in overall charge of the new Illyrian dispensation, Postumius sailed back to Italy with all his forces. The Romans were pleased enough to award both consuls triumphs. It was the start of a series of dazzling triumphs awarded for eastern victories.

ROMAN INTENTIONS

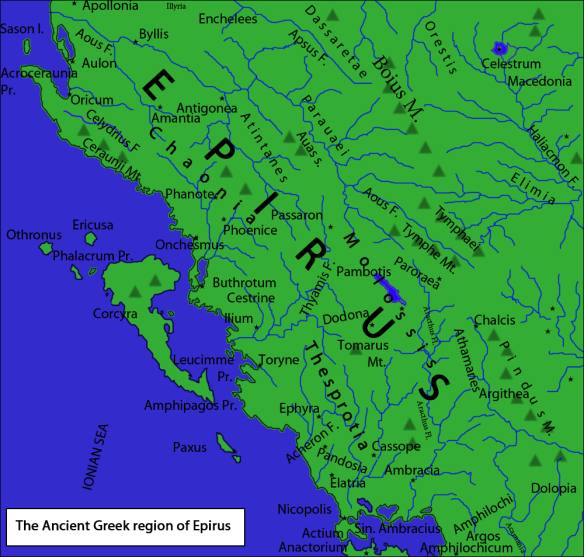

As wars go, this was very slight. Nevertheless, its outcome was important in that by 228 the Romans had established a zone of influence in Illyris, or rather, since it is not clear that all the lands involved were contiguous, a number of zones of influence. The most important elements were the Greek cities of Epidamnus, Apollonia, and Oricum; the islands (Corcyra, Pharos, Issa); and two tribes, the Parthini (in the Genusus valley) and the Atintani (around Antigonea and Byllis). Large parts of Illyris were now free to govern themselves in their own ways, as they had before, but now under the oversight of Demetrius of Pharos and the promise of protection by Rome.

The nature of the zone of influence (to continue with the singular for convenience) is significant; a glance at a relief map shows why. Epidamnus, Apollonia, and Oricum were not just fine harbors, but controlled about 90 percent of the Illyrian lowlands—all the best land for cereals and pasture. It is hardly surprising, then, that neighboring tribes also recognized their dependency on Rome: as largely mountain-dwelling transhumant pastoralists, they needed the fertile lowlands for their winter pasturage. Then the rest of the zone consisted of the wealthiest Greek islands of the Adriatic. The Romans effectively gave control of southern Illyris to the Greeks who lived there, and removed it from the Illyrians themselves; hence, again, Lissus was the cut-off point, because it was a specifically Illyrian town, not a Greek colony. The purpose was to allow southern Illyris to develop into a civilized, Greek confederacy of communities, initially under Demetrius of Pharos, perhaps in much the same way that Epirus had recently been modernized by Pyrrhus.

This result was always part of the Roman plan: as soon as they came, they began to issue the invitation of friendship. They wanted to enter into a long-term relationship with the southern Illyrian states, but understanding their reasons for doing so is difficult and requires the rigorous elimination of hindsight. On the one hand, one might argue that nothing was going on apart from what appears on the surface: the Romans’ intention was to quell the Illyrians. To think anything else is to use hindsight, because the Romans did eventually come as conquerors of Macedon, and control of the Illyrian ports was indeed critical for that enterprise. But for the time being they came as friends, making use of their superior strength and leaving their new friends the right to call on them if they needed to.

On the other hand, the friendship that the Romans offered the Illyrians was a familiar aspect of their relations with others. The conquest and subjugation of Italy had proceeded only partly by establishing formal treaties, but largely on the basis of similar kinds of informal relationship. Southern Illyris was basically an extension of the same system that was in force in Italy, and that system was a means of subordination. That is what the Romans intended in southern Illyris as well—not out of sinister motives, but just because that was the way they acted. That was the only kind of relationship with lesser states that they felt was possible. Illyris at a stroke became a place where the Romans were interested in establishing and maintaining dominance.

For Polybius (as a Greek), the Romans’ first military contact with the Greek world was highly significant. He was right: it would indeed lead to catastrophic changes for Greece. But they were a long way off. Annexation was not yet on the Romans’ minds. They withdrew this time, and they would do so again. But each time they left a greater degree of dependency behind them. They were a small state rapidly learning to think big, learning to adjust their view of themselves to the vastly increased horizons the First Punic War had afforded them. Only when they had regained their focus—in the first flush of appreciation of the benefits of empire—would they be ready to expand their horizons again. In the meantime, they had established in Illyris a sphere of influence.