The Bridge at Gorgopotamos after the Harling Mission

The Greek Army had managed to hold off the Italian offensive into the country starting in October 1940. A stalemate had been created along the Greek border with Albanian, and it remained as such until the German intervention of 6 April 1941. The Germans invaded from Yugoslavia and allied Bulgaria, bypassing the Greco-Italian frontline and made a rapid advance down the mountain roads against the gradually failing defence of the Greek and Allied armies. Hitler required the pacification of the region for his upcoming assault on Soviet Russia. He did not want his southern flank left open to pro-Allied nations that could interfere with his assault. The Greeks would not react well to being occupied.

Two major resistance forces would rise from the Greek capitulation, both under differing ideologies. The first would be raised by Athanasios Klaras, an artillery major in the Greek army who had been court martialled down to corporal and sent to the Greco-Italian front. He would fight under the nom-de-guerre: Aris Velouchiotis and was of pro-communist persuasion. His group would become known as ELAS, the Greek People Liberation Army. He would walk into villages asking for their support, and would especially recruit mountain bandits, familiar with the mountainous regions of Greece.

On the other side of the political divide was EDAS, the National Republican Greek League. This was commanded by Napoleon Zervas and was anti-monarchist and pro-social democracy. This unit would operate predominantly in the Epirus region of Greece. Both forces, though fierce rivals, were sceptical of Allied support and involvement in the region.

However this was to change in mid-1942 when both units would be called upon by the SOE to aid in the destruction of a railway viaduct north of Piraeus. The Eighth Army under General Bernard Montgomery in North Africa was building up to its major offensive at El Alamein that would finally push Axis forces out of Egypt. It was thought that any disruption to the Axis supply lines would be advantageous to the assault. The Axis forces were supplied via two routes, through Italy and Sicily or through Greece. The Greek route utilised the main railroad that led through the country from Thessalonika in the north down to Athens. Three railroad viaducts were chosen as potential targets; at Gorgopotamos, Asopos and Papadice and an SOE assault team of twelve men were assembled.

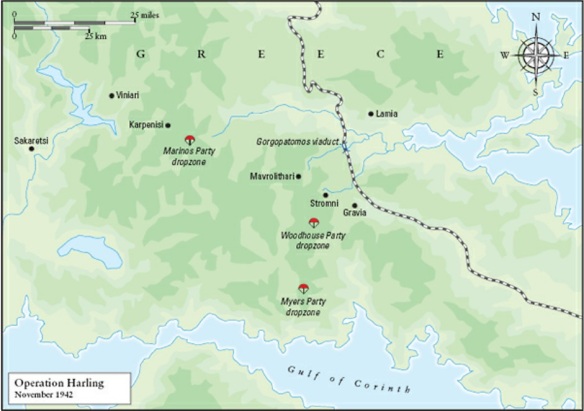

The mission was to be commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Eddie Myers, splitting the group up into three groups of four, each containing a commander, an interpreter, a sapper and a radio man. The men were to be dropped by three RAF B-24 Liberators flying from Cairo on the 28 September 1942, with the hope of contacting the local resistance. Little information could be given on how to contact these parties. This was abandoned as the pre-arranged fires that were to be lit to locate the landing zones could not be found. Two days later the drop went ahead, two of the groups landing near Mount Girona whilst the third would land near the town of Karpenissi, some distance away. All the men once they hit the ground were immediately taken in by the locals and hidden from patrolling Italians, alerted by the low flying bombers.

Contact was made by the Karpenissi group, led by Major John Cooke with ELAS and they were taken to meet Velouchiotis. He was initially reticent about the raid, feeling that the main resistance was to be carried out in the occupied cities, but once he understood the strategic situation he agreed to participate.

Elsewhere a group led by Major Chris Woodhouse, second in command of the operation, made contact with EDAS and their leader Zervas, who immediately offered support and troops for the attack. Myers meanwhile was taken by local Greek guides to make a reconnaissance of the prospective targets, eventually choosing Gorgopotamos as it had the best route for infiltration and exfiltration, along with the least amount of garrison troops, about 100 Italian troops. After ten days all three groups were reunited, along with their new found allies.

The stage was set for the attack to go in on the night of 25/26 November. The Greek resistance fighters were tasked with assaulting both ends of the bridge to hold down the Italian garrison, this they did just before midnight, throwing grenades into the pillboxes at either end which kicked off an enormous firefight. Whilst this was going on above their heads the SOE demolition team moved up the valley to the base of the viaduct. Here they attached explosives to one of the main piers. This was ignited at 01.30, causing two of the spans to drop into the valley. Deciding that more destruction could be had the demolition teams went back to attach more explosives to a remaining pier and on ignition dropped a further span. By 04.00 the attack was called off and the men withdrew, with only four wounded as a result. A day later the Italians would retaliate by executing fifteen civilians.

The attack was considered a success as it caused Hitler to move more troops from the fighting in Russia to reinforce his southern frontier, afraid that an Allied invasion may come via the Balkans and threaten his precious oilfields in Rumania. It was also a morale boost not just for the Greek people but also to SOE, proving that resistance and sabotage attacks could be fruitful.

Eddie Myers along with Chris Woodhouse, who could speak fluent Greek, were ordered to stay behind after the raid and remain as the British Military Mission to the country. The pair would again launch a similar attack on the Asopos railway bridge. This time it was a lot harder to approach as it was situated in a deep, vertical gorge and garrisoned now by German troops. With the aid of additional sappers the team of six British engineers crept down the gorge to the base of the bridge. Once here two men climbed the supports and laid the charges. They then stole away and watched with relish the destruction of the bridge. The Germans would repair the bridge in record time, thanks to enforced labour. However the first train to cross would collapse the bridge once more.

Myers would then be pulled out of Greece over political reasons but Chris Woodhouse would remain in Greece as head of the Military Mission.

The resistance on Crete was very much a thorn in the German garrisons side. Here the population were a ferociously proud people and took great offence at the German invasion of May 1941. So much so that during the airborne assault men, women and even some children took up what little arms they had, usually aged rifles or knives, and joined in the defence. This was too little effect as the Allied army was soon pushed off the island. The Cretans would not give up their island so easily though, many of the Cretan soldiers involved in the defence fleeing into mountain hideaways where they would become ‘Ardartes’–mountain guerrillas. They would be aided by all of the islands inhabitants despite brutal German reprisals.

The island of Crete was of great strategic importance as it was on the supply route from Hitler’s oilfields of Rumania to the battlefields of Northern Africa, this led SOE to send numerous liaison teams to assist the Cretan resistance with supply and planning.

Two such men of the SOE that would become infamous on Crete were Major Patrick Leigh Fermor and Captain Bill Stanley Moss. Fermor could speak fluent Greek and was to spend over two years of the war on Crete. In Cairo these two men would meet and hatch a plan that would boost the morale of the occupied islanders whilst simultaneously lowering the morale of the German garrison. They were to capture the German Military Governor on the island, General Friedrich Wilhelm Muller, and spirit him away to Egypt. He had been guilty of committing many atrocities on the island including starving villagers into submission as well as flattening entire towns as reprisal to any attack on German troops.

Leigh Fermor was dropped on Crete on 4 February, Moss being unable to make the drop. He would rejoin Leigh Fermor the following April via motor launch from Egypt. By this time the Military Governor role had been taken by General Heinrich Kreipe, but it was thought that the kidnapping should still go ahead.

On the evening of 26 April 1944 Leigh Fermor, Moss and a kidnap team of five Ardartes set up a road block on the road from Kreipe’s villa to his headquarters in Heraklion. Whilst the Cretans hid themselves in the surrounding scrub the two SOE men, dressed as German corporals awaited the arrival of the General’s car. As it approached the men casually waved it down for an inspection, much to the annoyance of Kreipe, who had given specific instructions not to stop his car. As soon as Leigh Fermor identified the General, Moss coshed the driver and the Cretans jumped from their hiding places, quickly securing the general in the back. Moss then drove with Leigh Fermor posing as the general, wearing his peaked cap, through numerous checkpoints until they were through Heraklion. The team then took to the mountains in order to lose any pursuers and make the rendezvous on the southern coast of the island with a Royal Navy launch whilst Leigh Fermor continued on with the car. Further down the road he would abandon it, leaving materials that would lead the Germans to suspect it was a British only raid, therefore averting any reprisals. Leigh Fermor would then rejoin the party in the mountains.

The Cretans supplied the General with a mule to aid his ascent of the steep mountain paths, and Leigh Fermor and Kreipe would bond over their mutual appreciation of ancient writing. As the days went by the team would take shelter near to mountain villages in order to attain supplies, happily donated by the people within them. Thanks to the network of villages the townsfolk would know of their imminent arrival and prepare, even though a large proportion of the island knew of this plan no information was ever given to the Germans in pursuit. On 14 May, after an eighteen-day trek over the mountains of Crete, which included Mount Ida, the team arrived at a beach near Rodakino where a launch picked up the General and the SOE men and took them back to Egypt.

The Germans would never break the spirit of the Cretan people and the Andartes. The Germans were often unnerved by their unwavering bravery even in the face of a firing squad. Thanks to the activities of the resistance on the island a total of 100,000 troops would be garrisoned here, troops that were desperately needed on other fronts. This was achieved at a very high cost in lives to the islanders of Crete.