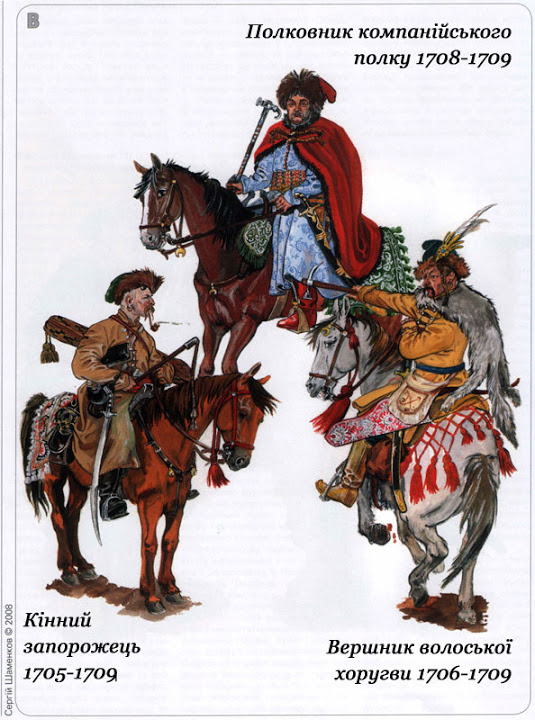

1. Horse Zaporozhian Cossack, 1705-1709, took participation in almost all main stages of Great Nordic war on both sides; 2. The colonel of the Campaign’s regiment (mercenary), 1708-1709; 3. Horseman of the Wallachian (Moldavian) regiment, 1706-1709, were an essential part of the mercenary Cossack forces since the late 17th century.

The battle for the loyalty of the Cossacks and the inhabitants of the Hetmanate had begun. It was carried on mainly through proclamations issued by Peter, to which Mazepa responded in kind. The so-called war of manifestos lasted from the fall of 1708 to the spring of 1709. The tsar accused Mazepa of treason, calling him a Judas and even ordering that a mock order of St. Judas be prepared for awarding to Mazepa once he was captured. Mazepa rejected the accusations. Like Vyhovsky before him, he regarded relations between the tsar and the hetman as contractual. As far as he was concerned, the tsar had violated the Cossack rights and freedoms guaranteed to Bohdan Khmelnytsky and his successors. His loyalty, argued the hetman, was not to the sovereign but to the Cossack Host and the Ukrainian fatherland. Mazepa also pledged his loyalty to his nation. “Moscow, that is, the Great Russian nation, has always been hateful to our Little Russian nation; in its malicious intentions it has long resolved to drive our nation to perdition,” wrote Mazepa in December 1708.

The war of manifestos, along with the decisive actions of the Muscovite troops and the election of a new hetman on Peter’s orders, caused another split in Mazepa’s ranks. Terrified by the prospect of retributions, the Cossack colonels who had earlier pressured Mazepa to rebel failed to bring their troops to him. Many joined the Muscovite side. There was little support for Mazepa on the part of rank-and-file Cossacks, townspeople, and peasants. The populace preferred the Orthodox tsar over the Catholic, Muslim, or, in this case, Protestant ruler. When the time came for a showdown between Charles and Peter, there were more Cossacks on the Muscovite side than on the Swedish one.

In early July 1709, a Swedish corps of 25,000 faced a Muscovite army twice as large in the fields near the city of Poltava. Cossacks fought on both sides as auxiliaries—a reflection not only of the fact that their loyalty was suspect but also that they were no match for regular European armies: the once formidable Cossack fighting force was a thing of the past. Between 3,000 and 7,000 Cossacks backed Mazepa and the Swedes; at least three times as many flocked to the Muscovite side. The enemy’s numerical superiority was never an issue for Charles XII, who had defeated much more numerous Russian and Polish forces in the past. But this battle was different. A winter spent in hostile territory had weakened his army. Charles XII, who usually led his troops into battle in person, had been wounded a few days earlier and delegated his duties not to one commander but to a number of officers, creating confusion in the Swedish ranks at the time of the battle.

The outcome was a decisive victory for Muscovite arms. Charles XII and Mazepa had to flee Ukraine and seek refuge in Ottoman Moldavia. Ivan Mazepa died in exile in the Moldavian town of Bender in the fall of 1709. It took Charles five years to get back to his kingdom. Historians often consider the Battle of Poltava a turning point in the Great Northern War. By a strange turn of fate, the military conflict for control of the Baltics was decided on a Ukrainian battleground, undermining Sweden’s hegemony in northern Europe and launching Russia on its career as a great European power. But the consequences of Poltava were nowhere as dramatic as in the lands where the battle was fought.

The Muscovite victory opened a new stage in relations between the Kyivan clergy and the tsarist authorities. In the fall of 1708, the tsar had forced the metropolitan of Kyiv to condemn Mazepa as a traitor and declare an anathema against him. After the battle, the rector of the Kyivan College, Teofan Prokopovych, who had earlier compared Mazepa to Prince Volodymyr, delivered a long sermon before the tsar condemning his former benefactor. What Mazepa would have considered treason was a declaration of loyalty in Peter’s eyes. Prokopovych would later become the chief ideologue of Peter’s reforms. He would support the tsar’s drive for absolute power and develop an argument for his right to pass on his throne outside the normal line of succession from father to son: Peter tried his only male heir for treason and caused his death in imprisonment. Prokopovych was the primary author of the Spiritual Regulation, which replaced patriarchal rule in the Orthodox Church with the rule of the Holy Synod, chaired by a secular official. He was also behind the idea of calling Peter the “father of the fatherland,” a new designation brought to Muscovy by Prokopovych and other Kyivan clerics. They had earlier used it to glorify Mazepa.

The spectacular imperial career of Teofan Prokopovych reflected a larger phenomeno n—the recruitment into the imperial service of westernized alumni of the Kyivan College, whom Peter needed to reform Muscovite church culture and society along Western lines. Dozens and later hundreds of alumni of the Kyivan College moved to Muscovy and made their careers there. They assumed positions ranging from acting head of the Orthodox Church to bishop and military chaplain. One of the Kyivans, Metropolitan Dymytrii Tuptalo of Rostov, was even raised to sainthood for his struggle against the Old Belief. They helped Peter not only to westernize Muscovy but also to turn it into a modern polity by promoting the idea of a new Russian fatherland and, indeed, a new Russian nation, of which Ukrainians or Little Russians were considered an integral part.

If Peter’s policies intended to strengthen his authoritarian rule and centralize state institutions offered new and exciting opportunities to ecclesiastical leaders, they were nothing short of a disaster for the Cossack officers. Mazepa’s defection added urgency to the tsar’s desire to integrate the Hetmanate into the institutional and administrative structures of the empire. A Russian resident now supervised the new hetman, Ivan Skoropadsky. His capital was moved closer to the Muscovite border, from the destroyed Baturyn to the town of Hlukhiv. Muscovite troops were stationed in the Hetmanate on a permanent basis. Family members of Cossack officers who had followed Mazepa into exile were arrested and their properties confiscated. More followed once the Northern War ended with a Muscovite victory in 1721. Tsar Peter changed the name of the Tsardom of Muscovy to the Russian Empire and had himself proclaimed its first emperor. In the following year, the tsar used the death of Skoropadsky to liquidate the office of hetman altogether. He placed the Hetmanate under the jurisdiction of the so-called Little Russian College, led by an imperial officer appointed by Peter. The Cossacks protested and sent a delegation to St. Petersburg to fight for their rights—to no avail. The tsar ordered the arrest of the leader of the Cossack opposition, Colonel Pavlo Polubotok, who would die in a cell of the St. Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg.

Mazepa had gambled and lost. So did the state he tried to protect. We do not know what the fate of the Hetmanate might have been if Charles XII had not been wounded before the battle and the Cossacks had supported Mazepa in larger numbers. We can say, however, what kind of country Mazepa’s successors wanted to build and live in. Our knowledge comes from a document called Pacta et conditiones presented to Pylyp Orlyk, the hetman elected by the Cossack exiles in Moldavia after Mazepa’s death. Needless to say, they did not recognize Skoropadsky, elected on Peter’s orders, as their legitimate leader. The Pacta, known in Ukraine today as the Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk, is often regarded as the country’s first constitution, adopted, many say with pride, even before the American one. In reality, the closest parallel to the Pacta would be the conditions on which the Polish Diets elected their kings. The document tried to limit the hetman’s powers by guaranteeing the rights of the Cossack officers and the rank-and-file Cossacks, especially the Zaporozhians, many of whom had followed Mazepa into exile.

The Pacta presented a unique vision of the Hetmanate’s past, present, and future. The Cossack officers gathered around Orlyk, who had been Mazepa’s general chancellor, traced their origins not to Kyiv and Prince Volodymyr—a foundational myth already claimed by Kyivan supporters of the tsar—but to the Khazars, who were among the nomadic predecessors of Kyivan Rus’. The argument was linguistic rather than historical, and, while laughable today, it was quite solid by the standards of early modern philology: “Cossack” and “Khazar” sounded quite similar, if not identical, in Ukrainian. At stake was a claim to the existence of a Cossack nation separate and independent from that of Moscow. Orlyk and his officers described it as Cossack, Ruthenian, or Little Russian, depending on circumstances. Most of Orlyk’s ideas remained unknown or unclaimed by his compatriots. At home, in Ukraine, the Cossacks were fighting hard to preserve whatever was left of their autonomy.

The Cossacks in the Hetmanate regarded the death of Peter I in February 1725, a few weeks after the demise of the imprisoned Cossack colonel Polubotok, as divine punishment for the tsar’s mistreatment of them. They also viewed it as an opportunity to recover some of the privileges usurped by the tsar. The restoration of the office of hetman topped the Cossack agenda. In 1727 the Cossack officers achieved their goal by electing one of Peter’s early opponents, Colonel Danylo Apostol, to the newly reinstated hetmancy. They celebrated this restoration of one of the privileges given to Bohdan Khmelnytsky by rediscovering a portrait of the old hetman and reviving his cult not only as the liberator of Ukraine from Polish oppression but also as a guarantor of Cossack rights and freedoms. In his new incarnation, Khmelnytsky became the symbol of the Hetmanate elite’s Little Russian identity, which entailed the preservation of special status and particular rights in return for political loyalty.

What exactly was that new identity? It was a rough-and-ready amalgam of the pro-Russian rhetoric of the clergy and the autonomist aspirations of the Cossack officer class. The main distinguishing feature of the Little Russian idea was loyalty to the Russian tsars. At the same time, Little Russian identity stressed the rights and privileges of the Cossack nation within the empire. The Little Russia of the Cossack elite remained limited to Left-Bank Ukraine, distinct in political, social, and cultural terms from the Belarusian territories to the north and the Ukrainian lands west of the Dnieper. The DNA of the new polity and identity bore clear markers of earlier nation-building projects. The Cossack texts of the period (the early eighteenth century saw the appearance of a new literary phenomenon, Cossack historical writing) used such terms as Rus’/Ruthenia, Little Russia, and Ukraine interchangeably. There was logic in such usage, as the terms reflected closely interconnected political entities and related identities.

In defining the relationship between these terms and the phenomena they represented, the best analogy is a nesting doll. The biggest doll would be the Little Russian identity of the post-Poltava era; within it would be the doll of the Cossack Ukrainian fatherland on both banks of the Dnieper; and inside that would be the doll of the Rus’ or Ruthenian identity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At its core, Little Russian identity preserved the memory of the old commonwealth Rus’ and the more recent Cossack Ukraine. No one could know, in the aftermath of the Battle of Poltava, that it was only a matter of time before the Ukrainian core emerged from the shell of the Little Russian doll and reclaimed the territories once owned or coveted by the Cossacks of the past.