Left to Right: U.S. Commanders in Italy / 1- Major-Gen Alfred M. Gruenther, Chief of Staff 15th Army Group 2- Lt-Gen Mark W. Clark, CG of 15th Army Group 3- General of the Army George C. Marshall 4- Lt-Gen Lucian K. Truscott, CG of 5th Army after Dec 1944. 5- Major-Gen Edward M. Almond, CG of 92nd Division 6- Lt-Gen Joseph McNarney – US Army Mediterranean Theater of Operations 7- Major-Gen Willis D. Crittenberger, CG of IV Corps.

“Smiling Al” Kesselring didn’t have much to beam about after the fall of Rome. Clark’s Fifth Army swung around the city and advanced into the coastal plain leading north, keeping up the pressure on the retreating Fourteenth Army. All the same, this wasn’t pursuit à l’outrance.

Clark had Truscott’s VI Corps and Juin’s Corps Expéditionnaire Français out front. This meant the pursuit was being led by the most tired, depleted divisions of the Fifth Army. These were the divisions earmarked to invade the south of France. Better use them while he still could, reasoned Clark.

In front of them, the Fourteenth Army was going backward on its knees. Three of its nine divisions were virtually wiped out; the rest were at half strength or less.

The German Tenth Army, pursued by the British Eighth Army, was up in the mountains of central Italy. Unlike the Fourteenth, it hadn’t suffered too heavily when Allied divisions had broken the Winter and Gustav lines. Even so, a huge gap had opened up between it and the Fourteenth Army. If the Allies drove through that gap, they could turn the Tenth Army’s right flank.

Clark, however, was not about to charge headlong after the Germans. Losing many of his best troops and much of his artillery had reduced the Fifth Army’s effectiveness. Nor was he much convinced by the picture Ultra presented of German weakness. Ultra had painted pretty pictures before, only for them to prove to be all smoke and mirrors.

Forty miles north of Rome he paused to reorganize the lineup of Fifth Army units. Truscott’s veteran VI Corps came out of the line to mount the amphibious assault on southern France. The brand-new IV Corps, commanded by Willis Crittenberger, moved in to replace it. Corps boundaries were redrawn and half a dozen divisions shifted around. The Allied army group commander, Field Marshal Alexander, grumbled in his polite, aristocratic style that maybe this kind of thing was helping the Germans get away. The Eighth Army, though, moved even more slowly than the Fifth Army.

Kesselring fell back toward northern Italy with his two German armies, eagerly counting away the beautiful summer days and longing for winter again. Behind him Todt workers, helped by thousands of Italians, were creating yet another daunting line of fortifications. Called the Gothic Line, it followed the east-west line of mountains that marks the southern boundary of the Po Valley, 200 miles north of Rome.

Hitler expected Kesselring to stand and fight somewhere between Rome and the Po, yet reinforcements were few, losses many. Kesselring couldn’t draw a line on the map and refuse to take a backward step. To survive, he had to rely on an elastic defense: Hold bits of terrain that were easy to organize defenses around, make the pursuers stop, deploy, fight for them and, just as the position was ready to fall, pull out. Kesselring did it again and again, from mountain slope to river crossing, from ridge line to hilltop, buying a few days here, a few days there, and keeping an eye on the calendar.

He was helped too by logistical frustrations. The Fifth Army’s Roman fuel dump caught fire, turning a lake of gas into a cloud of smoke. Unable to feed itself, Rome had to be fed by the victors. What wasn’t given was taken. The Italian black market combined the Latin skills of seduction with the organizational wiles of the Mafia. Willing or not, the Army kept a lot of Italians alive and in business.

The drain on supplies strained a tight port situation to the breaking point. Advancing into northern Italy called for capturing more ports on both coasts, ports that were certain to be wrecked and explosive. And for every mile that the Allied armies advanced, there was a bridge or a culvert: rubble, rubble.

Following Clark’s reorganization, the pursuit resumed. Crittenberger’s troops advanced along the western coast of Italy. The French corps was on their right. Rome had been spared destruction. And now the French were advancing on Siena, an exquisite hill town of surpassing cultural importance in central Italy. De Gaulle pledged that if anyone harmed Siena, it wouldn’t be the French. Juin fought all around it, bypassing some positions and storming others, until he’d outflanked the town and cut into the German line of communications. On July 3 Siena fell unscarred to French soldiers who entered without firing a shot.

Crittenberger’s major objective was Livorno, a medium-sized port 150 miles north of Rome. He reached the outskirts on July 4, and the 34th and 91st divisions had to fight a two-week battle to take it. This was “Doc” Ryder’s last fight. Physically exhausted and in poor health, he was sent home. The 34th’s new commander was Charles Bolté, yet another onetime Benning student-turned-instructor under Marshall. Like Collins, Bolté was one of the masterminds behind triangularization and a maestro of the holding attack.

Livorno turned out to be the most booby-trapped place on the planet Earth. The Germans had reached a fiendish sophistication in the black art of absent maiming. To the usual perils of booby-trapped doors, windows, vehicles and weapons they reached out to embrace the most innocuous items—pencils, soap tablets, packets of gauze; anything that another human being was likely to touch. Every stone in Livorno seemed to shriek of death or mutilation. There’s no need to describe the state of the port.

From Livorno and Siena, the Fifth Army moved toward the Arno River. For all the measured pace of the pursuit, Kesselring’s armies were still hurting. He’d managed to shift troops from the Tenth Army over to the Fourteenth Army, preventing its collapse. But behind him a massive aerial onslaught against the bridges and ferries across the Po in mid-July came close to choking off the flow of food, fuel and ammunition.

To Alexander, this was the time to speed up the pursuit, to take a running jump at the Arno and plunge like a knife into the Germans on the far shore. Clark thought it was time for another pause.

The French had to depart, to help liberate France. When they left, so did various support units. The Fifth Army had now lost its two best corps—Truscott’s and Juin’s—leaving only the green IV Corps under Crittenberger and the II Corps, commanded by the plodding Geoffrey Keyes. And for all Alexander’s enthusiasm for hurrying the advance, the main burden of that would inevitably fall on the Fifth Army.

Although it was a variegated command with divisions from several countries, the Fifth Army had U.S. logistics. The British Eighth Army, commanded now by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese, plodded along at the same pace as it had done under Montgomery. Clark didn’t feel his depleted force was in any shape to be used as the Allied spearhead in a renewed offensive. He ignored Alexander’s prodding, and the Fifth Army took a thirty-day rest. The Germans used the time to restore bridges and ferries across the Po.

The key to the German position along the Arno was Florence. The British closed on the city, shut down its water supply and cut its electric power lines. The Germans dug in on either side of the city and put up a fight, but this too was just one more delaying action. On August 4 Florence fell undamaged, if only just, into Allied hands.

Its capture ended the campaign for Central Italy, a campaign that had begun three months earlier with the breakout from the Gustav Line. On a clear day, from the lovely but battle-marked Belvedere overlooking Florence, Allied soldiers had a thrilling view of the mountains 50 miles away, where the Gothic Line was being built with appalling haste to greet them.

The Gothic Line was the position Hitler had planned to fall back to when the Allies invaded Italy. He’d sent Rommel to supervise its construction and fight the battle there. It was those intentions, picked up by Ultra, that convinced the British that Italy—most of it anyway—was going to fall fast and cheap. “Smiling Al” changed all that by fighting south of Rome and dragging the Führer along with him.

Nevertheless, Churchill and Brooke hadn’t changed their minds about Italy, the gateway to all kinds of good things: a quick end to the war, keeping the Russians out of Western Europe, saving the Balkans from Communism, tying down huge numbers of Germans easily with small numbers of Allied troops, and so on. After 1945 a legend arose that if only Churchill’s ideas had been followed, the Cold War wouldn’t have happened, because Western troops would have reached Vienna ahead of the Red Army.

In trying to get Anvil scrapped, Churchill had certainly argued for an advance through the Balkans to Vienna. How he expected to get Stalin to agree to an anti-Russian strategy, he didn’t say.

The British believed, moreover, that if they could get to Trieste and into the Ljubljana Gap through northern Yugoslavia, they’d break straight into the Danube Basin. Marshall had some of the OPD’s ablest planners try to find a way to do it. To secure the passes through the Alps and into Austria called for hundreds of thousands of troops, yet they’d have to be supplied along a single narrow, circuitous road and a Toonertown Trolley railroad line winding among mountain peaks. It was simply impossible, even with U.S. logistics. Marshall worried, all the same, that Churchill might manage to sell his idea to Roosevelt.

Once he was convinced that Italy was the gateway to nowhere, Marshall wanted to see operations scaled down, not up. There was no strategic value in driving the Germans north. The farther north they retreated, the tougher it would be to defeat them. Once they got into the Alps, one German would be able to hold off half a dozen attackers. In World War I a few German and Austrian divisions holding key passes had frustrated the entire Italian army for three years.

Alexander and Leese nevertheless insisted on advancing from the Arno and trying to break through the Gothic Line. It was far from completed, and they didn’t propose to stand by and watch the enemy finish his handiwork.

The Germans evacuated the civilian population up to 15 miles south of the Gothic Line and created a “Dead Zone.” Years later this idea would reappear in Vietnam as the “free fire zone”—anything that moved in it was presumed to be enemy.

Behind the Dead Zone ran the main line of resistance, where hundreds of bunkers were blasted out of solid rock or made with reinforced concrete. Each held five men and a machine gun. In front of every bunker was a swath of barbed wire 25 feet deep. On reverse slopes were big dugouts that held up to 20 men armed with mortars and machine guns. Antitank guns were dug in along the line, and a mobile reserve of SP artillery was maintained behind it.

The line was 150 miles long, though, and Kesselring hadn’t enough troops or guns to make it really strong for even half that distance. He had to guess where the attack would come. The most vulnerable area was on his left flank, on the Adriatic side of Italy. He decided to concentrate there.

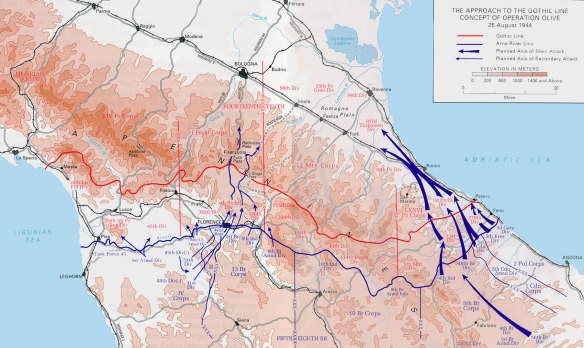

At about the same time, Leese was deciding that was where he’d attack. By driving along the Adriatic coast, he’d be heading toward Trieste. From the Arno, then, the two Allied armies advanced toward northeastern Italy and the strategically important city of Bologna.

Clark went along with Leese’s plan to attack this end of the Gothic Line, on condition that the British XIII Corps be assigned to the Fifth Army; otherwise he feared his army would be too weak to take its assigned objectives.

In private, Clark didn’t think Leese’s plan to break through the Gothic Line would work. He had no faith in the Eighth Army. It had become lackluster. Confidence had been bled out of it, to be replaced by an obsessive concern with casualties. Nor was the plan impressive. All the American officers on the Joint Planning Staff said it would fail.

They hadn’t allowed, however, for the 2nd Polish Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Wladyslaw Anders. The Poles had taken little part in the pursuit; they harnessed their strength and received 10,000 replacements. As the Germans were defeated, large numbers of Poles who’d been forced to work for Organisation Todt or been impressed into German units became Allied prisoners. They were given the chance to serve in the Polish Army. Anders was a tough, able soldier, like the men he led.

The Eighth Army advanced the 30 miles from the Arno to the Dead Zone against slight German resistance. The assault began on August 25. For a week the hard-pressed Germans held their ground, but only by throwing in their carefully husbanded reserves. On September 2 the Poles outflanked the line by taking the Adriatic fishing town of Pesaro. Overnight, they’d undone months of German construction.

Leese seemed poised to break into the Romagna, the huge fertile coastal plain centered on Bologna. Once on the plain, the British expected to advance rapidly on the city from the south while the Fifth Army, attacking the center of the Gothic Line, would converge on Bologna from the southwest. In Italy there was no pretense that only by putting everything behind one thrust could Allied armies advance on major objectives. Alexander, like generals down the ages, believed in converging attacks.

The Eighth Army’s success along the Adriatic shore drew German reserves away from the center of the Gothic Line just before Crittenberger’s corps launched its assault. Breaking through in the center hinged on capturing two narrow, strongly guarded mountain passes called Futa and, 10 miles to the northeast, Il Giogo.

Bolté had the 34th Division make a holding attack against Futa, pinning down the Germans, while the 85th and 91st divisions made a wide flanking movement that struck Il Giogo and drove the defenders through it. Outflanked, Futa was untenable. The Germans abandoned it.

Clark and Leese had both broken through the Gothic Line. The war in Italy looked as though it would end in 1944. Alas, these September successes took place in ominously heavy rains that grounded air support and artillery spotter planes. The Eighth Army bogged down short of the Romagna and 25 miles from Bologna.

Clark was still in the mountains. He too was 25 miles short of Bologna. Early in October he put Keyes’s II Corps into action with a fresh offensive to reach the city. It got to within nine miles of Bologna before lurching to a halt.