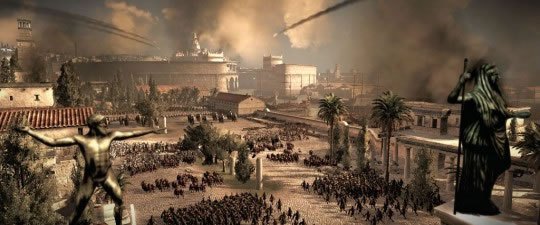

Depiction of Kitos War

“THEY WOULD COOK THEIR FLESH”

The origins of and much of what occurred during the Kitos War, as the Second Jewish-Roman War came to be known, remains shrouded; it did not have an historian like Josephus to record the story. But it is obvious that the Jews, feeling themselves to be an oppressed minority, rose up with a vengeance. Interestingly, the Kitos War began not in Judea, but in the provinces where diasporic Jews had gone subsequent to being ousted from Jerusalem.

The Kitos War—Kitos is a corruption of the name Lusius Quietus, the Roman commander who eventually put down the revolt—was an especially bloody one. The Roman historian Dio Cassius wrote of the first rebels under Lukuas, or Andreas:

Meanwhile the Jews in the region of Cyrene had put one Andreas at their head and were destroying both Romans and Greeks. They would cook their flesh, make belts for themselves of the entrails, anoint themselves with their blood, and wear their skins as clothing. Many they sawed in two, from the head downwards. Others they would give to wild beasts and force still others to fight as gladiators. In all consequently, 220,000 perished…

Dio Cassius, writing within fifty years after these events, may have been prejudiced against the Jews, but other sources say that Libya was practically depopulated after the Kitos War, lending some credence to Dio Cassius’s casualty figures (he also stated that 240,000 died in Cyprus, where the revolt would spread). The atrocities that Dio Cassius attributes to the Jews were the same ones that the Romans had perpetrated against the Zealots they had defeated in the First Jewish-Roman War. Obviously, the war against the Romans had never really ended. Kept alive by simmering hatred, it burst into flame again.

In 116, Lukuas led his army into Alexandria to join the rebellious Jews there, and put the city to the torch after the Roman governor and his troops fled for their lives. In the ensuring months, the Jews terrified Egypt, despoiling the countryside and attacking the city of Thebes. The Jewish revolt now broke out in Cyprus, under another charismatic leader named Artemion, and spread to regions the Romans had newly conquered in Parthia.

General Lusius Quietus

Emperor Trajan had to do something. In 117, he sent two Roman legions to the area under the command of Lusius Quietus (Quietus, originally a Berber from Morocco, was one of the few blacks to succeed in the Roman military world of that era). Quietus’s men made fairly easy work of Lukuas and Artemion’s armies—which, according to some sources, were less armies than armed mobs—but then went further. Because Trajan was afraid that the Jews would rise up again and that their revolt would spread farther into the empire, he ordered Quietus to wipe out as many Jews in Egypt, Parthia, Cyrenaica, and Cyprus as he could. The killing was so effective in Cyprus that not one Jew remained and Jews were then forbidden to set foot on the island.

In major cities like Alexandria and Cyrene, Lusius confiscated Jewish property to pay for the reconstruction of the destroyed temples and also attempted to force Jewish children to be raised as secular Greeks. Once again, as with the First Jewish-Roman War, all this persecution merely made the Jews more resentful and prolonged the war. And their religion began to take an even deeper messianic turn. As the war ended in 117, some Jews were predicting that the end of the world was imminent.

THE NEW REVOLT

Judea after the First Jewish-Roman War had never been a quiet place. There were almost continuous instances of Jewish hostility to Romans—the mood of the country remained so rebellious that many Roman legionaries, having finished their twenty-year stint, were not discharged. There had been insurrections in Judea during the Kitos War—in fact, Lusius Quietus had been sent to put them down and had then stayed on as procurator, as reward for his services.

Emperor Trajan died at the end of 117, to be replaced by Hadrian, who mistrusted Quietus’s popularity among the Romans and had him executed. Shortly after this, Hadrian told the Jews of Jerusalem that he would rebuild the city (which had not yet recovered from being razed by Titus) and allow them to rebuild their own Temple as a Jewish Temple. However, in 130, Hadrian visited Judea and announced that he had changed his mind. His plan now was to have the entire city rebuilt into a Roman city with a huge temple celebrating the Roman god Jupiter. Historians can only speculate as to why he changed his mind—possibly because the Jews had reacted so emotionally to his first offer to allow them to keep their Temple that he feared they might use it as a rallying point against him. In any event, according to the historian Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson, in his A History of the Jewish People, Hadrian now decided “to convert Jerusalem into a pagan city, without regard for its past or its place in Jewish thought and aspirations.”

And he did one more thing. Hadrian hated any religion or religious practice that he considered exotic and unusual, and one of these practices was circumcision, which he equated with castration. He therefore banned circumcision under penalty of death. This ban was not aimed just at the Jews, but because circumcision was a primary religious rite of the Jews, it struck them where they lived. (There is another, more moderate historic interpretation of Hadrian’s ban, which reads it as a ban only on circumcision of boys who have not yet reached the age of consent.) And so they began again to secretly prepare for war against the Romans. Dio Cassius says that Jewish armorers would damage swords and spears given to them to repair, so that the Romans would reject them—and then the Jews would turn them back into functioning weapons in hidden armories.

The Jews bided their time and finally chose to revolt in the beginning of 132, possibly because the ongoing Roman construction work in Jerusalem had caused the tomb of Solomon to collapse, a sacrilege within a sacrilege. All over Judea, armed Jewish guerillas now rose up, attacking Romans in small outposts.

SIMON, PRINCE OF ISRAEL

Little is known about the beginnings of the revolt, but from fragments of letters and documents found in caves in the Judean desert by modern archeologists, we now know that the charismatic leader of the Jews was a man known as Simon bar Kosiba, or Simon, Prince of Israel, which indicates that he was a messianic figure. He was also known as Bar Kokhba, or “Son of the Star,” which is how this Third Jewish-Roman War became known as the Bar Kokhba War.

Simon bar Kosiba was a real figure whose presence can be tracked by the letters he wrote, containing orders and land grants he made as his forces took over more and more of Judea and Galilee from the Romans. They track from the very first days of the rebellion, in April of 132, to the last days, in November of 135, indicating that bar Kosiba was in charge from the very beginning.

Many of his followers thought he was the messiah, the Son of David—there were rumors that he could shoot flames out of his hands to smite his enemies—while others did not. These included Jewish Christians who also joined in the fighting against the Romans and whom bar Kosiba supposedly ousted from his ranks if they refused to renounce Jesus.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt was the largest and bloodiest of the Jewish-Roman Wars, at once a continuation and a culmination of the first two conflicts, in which religion, nationalism, and extreme rage—Dio Cassius speaks of Roman troops being afraid to approach the Jewish rebels because of their “desperate anger”—all came to a head. Everything that had caused the conflict to go on as long as it did now lay at the heart of the terrible fighting between Jews and Romans.

The Bar Kokhba revolt was the largest and bloodiest of the Jewish-Roman wars, at once a continuation and a culmination of the first two conflicts, in which religion, nationalism, and extreme rage all came to a head.

At first, the Jews were successful, possibly beyond even their own dreams. Fighting against the Roman Tenth and Sixth Legions, the rebels were able to seize control of all of Judea, and much of the rest of the countryside. They may possibly have taken Jerusalem, although this is uncertain. For two and a half years, Simon bar Kosiba and his men ruled over a sovereign nation. They issued coins that showed the Ark of the Covenant and the Star of David and carried phrases such as “the freedom of Israel” and “the redemption of Israel.” They gave land that had been taken by the Romans back to Jewish farmers.

Roman governor Tinius Rufus tried harsh measures. According to the Greek historian Eusebius, “He moved out against the Jews, treating their madness without mercy. He destroyed in heaps thousands of men, women, and children, and under the law of war enslaved their lands.” Even so, Simon bar Kosiba and his men were able to control most of the country.

“WHO COULD HAVE OVERCOME HIM?”

The Romans then sent in Publius Marcellus, the governor of Syria, who brought with him Syrian legions as well as legions from Egypt and Arabia. The Jewish rebels beat these back, severely damaging the Roman Twelfth Legion (although not completely destroying it, as some sources have it). After that, in 133, the Jewish forces appear to have fought their way to the sea and may even have participated in a naval battle against the Romans, although this is uncertain.

Finally, in late 133 or early 134, Hadrian sent in Julius Severus, the governor of Britain, with his own legions and legions brought from the Danube. The Roman forces, with a dozen legions fighting, now far outnumbered those of Titus some sixty years before. They were able to push the rebels out of Galilee and fierce fighting now ensued in Judea. The Jewish rebels probably used guerilla hit-and-run tactics against the larger enemy force. According to Dio Cassius:

The rebels did not dare try to risk open confrontation against the Romans, but occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, so that they would have places of refuge when hard pressed and could communicate with one another unobserved underground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light.

Slowly, the Jews were pushed back through Judea in a series of bloody actions. The Romans themselves moved cautiously, as Dio Cassius once again wrote:

Severus did not venture to attack his opponents in the open at any one point, in view of their numbers and their fanaticism, but—by intercepting small groups, thanks to the number of his soldiers and under-officers, and by depriving them of food and shutting them up—he was able, rather slowly, to be sure, but with comparative little danger, to crush, exhaust and exterminate them. Very few Jews in fact survived. Fifty of their most important outposts and nine hundred and eighty-five better known villages were razed to the ground.

At last the Jews, Simon bar Kosiba among them, were pushed back to their fortress village of Betar, near a range of hills about three hours southwest of Jerusalem. There Kosiba and his command made their last stand in the spring and summer of 135. The Jews never surrendered, fighting until the last man. According to tradition, the Romans found the body of Simon bar Kosiba, cut off his head, and brought it to Emperor Hadrian, who reportedly said: “If his God had not slain him, who could have overcome him?”

“THE NOSTRILS OF THEIR HORSES”

In terms of barbarity, the war was the worst one of the three conflicts fought between the Jews and the Romans. The Romans supposedly wrapped children in the Torah and set them afire. According to Dio Cassius, 580,000 Jews died. However, Dio went on, so many Romans also perished that the emperor, in his letter to the Senate, “refrained from using the customary introductory phrase: ‘I trust you and your children are well; I and my troops are well.’”

The Romans got their revenge. They rooted out Jewish fighters in caves across the Judean desert (although there is archeological evidence that Jews remained in these caves for years). They refused to allow the Jews of Betar to bury the dead of the revolutionary fighters for seventeen years, leaving their bones strewn over the countryside. As retaliation, according to the Talmud, the Romans massacred so many Jews, rebels or not, that blood rose to the level of “the nostrils of their horses.” So many Jews were sold as slaves in marketplaces in Hebron and Gaza that they were worth less than a horse’s ration of grain.

Emperor Hadrian now refused to allow Jews to set foot in Jerusalem—a detachment of the Tenth Legion was stationed near Jerusalem until the fourth century, expressly to oust any Jews attempting to enter the city (those caught were imprisoned and sometimes tortured to death). In fact, Hadrian renamed Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina, dedicating it to Jupiter. Hadrian placed his equestrian statue in the Holy Temple.

The long wars of the Jews against the Romans were now truly over. There would not be another Jewish army until the twentieth century and Judea would stop being the center of Jewish religion and thought. Once again, as with the Carthaginians in the Punic Wars, a country that fought a long, destructive war against the Romans was destroyed. Well, the country was destroyed, but not the people. The Jewish religion and culture continued and thrived throughout all the centuries of the Diaspora, until the Jews finally returned to Israel in the mid-twentieth century—occasioning yet another long and bloody war