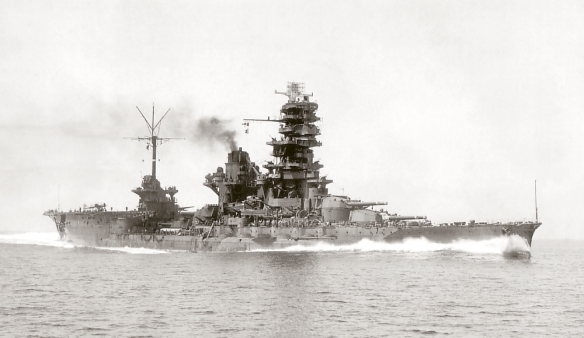

Hyūga after her 1943 conversion to a battleship/aircraft carrier.

USS Archerfish sinks Shinano.

In any other war the Japanese defeat at Leyte Gulf would have brought as speedy an end to hostilities as had the even more shattering defeat of the Russians at the hands of the Japanese at Tsushima in 1905. It is true that at Tsushima the Russian fleet had been annihilated, whereas after Leyte Gulf the Japanese still had a ‘fleet in being’ – but it was one that posed no threat to later American operations.

After the war, Vice Admiral Ozawa would state that Japan’s warships ‘became strictly auxiliary’. Those doughty warriors Hyuga and Ise, for example, were used to ferry loads of petrol from Singapore to Japan. Destroyers continued to land men and supplies at Ormoc Bay to aid their soldiers on Leyte, but American air supremacy made this a costly business. On 27 October, the airmen from Essex sank destroyers Fujinami and Shiranuhi and on 11 November, Third Fleet’s carriers sank destroyers Hamanami, Naganami, Shimakaze and Wakatsuki, not to mention a number of troop transports.

Most major Japanese surface warships remained uselessly in harbour, though this would not save them. While Seventh Fleet gave close support to the American forces on Leyte, Third Fleet concentrated on targets such as Manila, the main Japanese naval base in the Philippines. Aircraft from Lexington sank heavy cruiser Nachi in Manila Bay on 5 November. On the 13th, Third Fleet sank five more Japanese warships there: light cruiser Kiso and destroyers Akebono, Akishimo, Okinami and Hatsuharu. The harbour facilities at Manila were also damaged and large numbers of Japanese warplanes destroyed on nearby airfields. And on the 25th, heavy cruiser Kumano was sunk at Dasol Bay to the north of Manila by aircraft from US carrier Ticonderoga.

Japan’s own carriers also usually stayed in harbour. On the rare occasions when they ventured out, they did so singly and with baleful consequences. A particular thorn in their flesh was US submarine Redfish. On 9 December, she put two torpedoes into Junyo, damaging her so badly that she was out of action for the rest of the war. Not content with that, ten days later, Redfish attacked one of Japan’s latest carriers, Unryu. This time she scored only one hit aft, but it brought Unryu to a halt, on fire. Evading counter-attacks by escorting destroyers, Redfish attacked again and scored another hit. Unryu sank 20 minutes later.

At the time of Unryu’s loss, two sister-ships, Amagi and Katsuragi, were still afloat and three others, Aso, Ikoma and Kasagi, were under construction. By then, however, Japan’s industrial capacity was also starting to fail as the severance of her supply lines caused a lack of suitable materials. Early in 1945, work on all three uncompleted Unryu-class carriers ceased, as it did also on Ibuki, a proposed 12,500-ton carrier being converted from a cruiser, and on five smaller vessels being converted from tankers.

Only one of the carriers on which work was proceeding at the time of Leyte Gulf would ever be completed. This was Shinano, converted from the hull of a Yamato-class battleship. Of 68,000 tons displacement, almost 72,000 tons fully laden, she had a flight deck 840 feet long by some 130 feet wide, made of steel more than three inches thick. The armour of her hull and her hangar deck was eight inches thick, increasing to almost fourteen inches around her magazines. Yet when she left Tokyo Bay on her maiden voyage at 1800 on 28 November 1944, bound for Matsuyama near Hiroshima where she would complete her fitting-out, she had been made ready so hastily that her watertight compartments were not in fact watertight. Moreover, about 60 per cent of her crew had never previously served on a warship.

Late that evening, Shinano was sighted by US submarine Archerfish. This doggedly pursued her, aided by the fact that she was steering a zigzag course, until at 0317 on 29 November, a perfect firing position was reached and six torpedoes sped towards their target. At least four, possibly all of them, found their mark but Captain Toshio Abe, certain that Shinano was unsinkable, maintained course and speed while flooding continued unabated. At 1055, she rolled over and sank, taking Abe and some 500 of her crew with her. She was the shortest-lived capital ship ever to have gone to sea.

The decline of Japan’s industrial capacity, the poor workmanship on Shinano, the ability of US submarines to sink a major warship so close to the coast of Japan, the lack not only of experienced aircrew but of experienced seamen, all pointed to the helplessness of the Imperial Navy. Realization of this prompted Admiral Yonai and many of Japan’s leading naval commanders (but not Admiral Toyoda) to join their country’s civilian ministers and their Emperor’s advisers in urging that a continuation of the war was pointless and peace should be secured as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, President Roosevelt, with the concurrence of Churchill, had demanded the ‘unconditional surrender’ of the Axis powers. While some historians have argued that this had no adverse effects, few of those military leaders who had to deal with the consequences agree with them. Admiral Nimitz, for one, points out that it meant: ‘Terms would neither be offered nor considered. Not even Napoleon at the height of his conquests ever so completely closed the door to negotiation.’

Moreover the demand contradicted the claims of Britain and America that they had no quarrel with the people of the enemy countries, only their leaders. Chilling utterances of senior American officers that after the war the Japanese language would be spoken only in hell or that killing Japanese was no different from killing lice, seemed to indicate that if Japan surrendered unconditionally, no mercy would be shown. In apparent confirmation, on 24 November 1944, Superfortresses from Tinian in the Marianas began a series of attacks on Tokyo and other Japanese cities such as Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe. These culminated on the night of 9/10 March 1945 in a raid on the capital by over 300 bombers, openly acknowledged by the Americans as intended to destroy not just factories but large areas of the city and its inhabitants; it set more than 25,000 buildings ablaze, drove about a million homeless to seek shelter in the countryside and burned to death at least 83,000 civilians.

As a result, even the most moderate Japanese leaders dared not advise surrendering unconditionally and this immensely strengthened the position of the die-hards, of whom the chief was the War Minister, General Korichika Anami, whose desire was to raise a citizens’ army of men and women alike to confront any American invasion of Japan. As Nimitz rather cynically notes: ‘To adopt such an inflexible policy was bad enough; to announce it publicly was worse.’

So the war continued and since after Leyte Gulf warships were all but useless, the Imperial Navy’s best, almost its only effective weapon was its Kamikaze Corps. The suicide pilots’ principal targets would always be carriers and in consequence, from late 1944 onwards, the US ‘flat-tops’ as well as supporting and guarding landings, had to pay increasing attention to their own protection. As an illustration of this, in December 1944, Lexington and Ticonderoga, followed later by other fleet carriers, increased the number of their Hellcats by about twenty at the expense of a corresponding reduction in the strength of their strike aircraft.

That this attitude was both wise and necessary had already been demonstrated. On 28 October, an orthodox bombing raid on Third Fleet was broken up by the Combat Air Patrol and thirteen enemy aircraft destroyed for the loss of four Hellcats. Whereas on the 29th, carrier Intrepid was hit by a Kamikaze and slightly damaged, and on the 30th, Kamikazes hit Franklin and light carrier Belleau Wood, the former losing fifty-six men dead, fourteen injured and thirty-three aircraft destroyed; the latter ninety-two dead, fifty-four injured and twelve aircraft destroyed; and both being put out of action. And on 5 November, a Zero rammed Lexington; she remained fit for combat but another fifty dead and 132 wounded were added to Third Fleet’s casualty list.

A culmination to these assaults came with a whole series of suicide attacks on 25 November. Of the six Zeros that made for carrier Hancock, the Combat Air Patrol shot down all but one and this was blown up just in time by AA fire, only a blazing wing falling on the flight deck. Another Kamikaze, however, did hit and slightly injure Essex, and a second hit and a third near missed light carrier Cabot, the former damaging her flight deck, the latter tearing a six-foot hole in her hull. Two more crashed into the flight deck of the unlucky Intrepid, causing so much damage that she could no longer operate her aircraft. The Fast Carrier Force was temporarily withdrawn from Philippine waters.

Fortunately by this time the Americans were slowly but surely gaining the upper hand on Leyte Island. The decisive blow was struck on 7 December when Seventh Fleet landed in Ormoc Bay, taking the Japanese forces in the rear and preventing any more reinforcements from reaching them. By Christmas Day, MacArthur could declare that organized resistance had ended. Professor Morison wryly points out that ‘Japanese unorganized resistance can be very tough’ and mopping-up operations would continue until May 1945, but MacArthur was correct in believing that the Japanese now had no chance of recovering Leyte. The larger but strategically less important island of Samar had already been secured on 19 December.

In the Ormoc Bay Landings, aerial support had been provided by Army and Marine aircraft from Tacloban aerodrome on Leyte but American carriers were again present at the next step forward – to Mindoro on 15 December. The invasion was uneventful as there was only a sparse garrison on the island but there were plenty of Japanese airfields in the vicinity from which the landing force could be engaged. It was therefore covered by six of Seventh Fleet’s escort carriers, while Third Fleet’s fast carriers made preliminary strikes on enemy bases both in daylight and during the hours of darkness. For the loss of twenty-seven aircraft, mainly to AA fire, these destroyed some 170 enemy machines on the ground or in the air. The escort carriers’ pilots shot down twenty more.

Mindoro was followed by major landings at Lingayan Gulf on the north-west coast of Luzon, planned for 9 January 1945. General MacArthur was again in command and under him was Lieutenant General Krueger’s Sixth Army, carried by Vice Admiral Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet, with five escort carriers among the covering warships. Twelve other escort carriers supported the six battleships of Vice Admiral Oldendorf that were sent ahead to bombard shore positions. Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet provided distant cover.

On 3 January 1945, Third Fleet began preparatory assaults on airfields in Luzon, Formosa and Okinawa. In addition to seven large and five light carriers for daylight work, Halsey had a special Task Group built around carrier Enterprise and light carrier Independence for night operations. Carrier Essex had thirty-seven Corsairs on board as well as fifty-four Hellcats. This was the first time that Corsairs would see combat from an American carrier, though for almost a year they had served with British ‘flat-tops’. Sadly, their poor deck landing qualities persisted and during the next month, Essex would lose thirteen of them in accidents.

In all during these preliminary raids, Third Fleet lost forty-six aircraft in action, again chiefly from AA fire, and another forty operationally. Its airmen shot down only twenty-two enemy machines in combat but they also accounted for almost 200 on their own airfields. They did not, however, succeed in removing the greatest threat to Seventh Fleet: the Kamikazes.

Chief targets for these were the vessels of Oldendorf’s Bombardment Force. On the afternoon of 4 January, one crashed into the flight deck of escort carrier Ommaney Bay, starting a huge fire that reached her magazines. As explosions shook her, flames spread throughout her length and enormous clouds of smoke rose high into the air there was no alternative but to order ‘Abandon Ship’. She was finished off by an American destroyer.

On the 5th, a formation of fifteen bomb-carrying Zeros, with two more acting as escorts, delivered another suicide attack. It was led by Lieutenant Shinichi Kanaya who had repeatedly volunteered for such a mission but had hitherto been refused because of his value as a tireless trainer of Kamikaze units. Having had his wish granted at last, he directed a very efficient assault that damaged seven US vessels including escort carriers Manila Bay and Savo Island.

Next day, Oldendorf’s command reached Lingayan Gulf and thereby prompted a continuous series of suicide raids.1 Ten vessels including two battleships were damaged. One minesweeper was sunk, as were two more minesweepers on the 7th. On the 8th, Kinkaid’s main strength approached the Gulf and also came under attack, escort carriers Kadashan Bay and Kitkun Bay being rammed and so damaged that they had to withdraw from the combat-zone. Despite further attacks, however, the landings proceeded as planned next day. MacArthur, Krueger and their staffs went ashore on the 13th – on which date, Seventh Fleet had its last Kamikaze casualty: escort carrier Salamaua severely damaged.

While Seventh Fleet supported Sixth Army ashore and guarded its supply lines; Third Fleet, on 10 January, moved into the South China Sea, west of the Philippines. Here its aircraft continued to whittle down Japan’s surface warships. They had already sunk destroyer Momi near Manila on the 5th, and they now added light cruiser Kashii on the 12th, and destroyers Hatakaze and Tsuga on the 15th. They also sank a dozen tankers and over thirty other merchantmen. Third Fleet escaped any retaliation until it delivered a strike on Formosa on 21 January. This brought out the Kamikazes. First a Zero, then a Judy bomber crashed into carrier Ticonderoga, starting widespread fires and causing so much damage that she had to withdraw from the combat-zone. Other Judys rammed and damaged light carrier Langley and destroyer Maddox.

Soon afterwards, the whole of Third Fleet followed Ticonderoga out of the battle area and on 27 January, Admiral Spruance assumed command. Fifth Fleet as it therefore again became known, was somewhat different from Third Fleet because damaged ships had withdrawn, while new or repaired ones had replaced them; Corsairs had joined the Hellcats on Wasp, Bunker Hill and Bennington as well as on Essex; and Saratoga, like Enterprise, had become a night-action specialist. In all, Spruance commanded eleven fleet carriers and five light carriers; moreover Seventh Fleet, which remained in the Philippines to carry out a series of subsidiary landings, transferred its escort carriers, to become Fifth Fleet’s Support Force.