Modern historians have stressed that factionalism was one of the great weaknesses of the colony and contributed to its inexorable decline, but it is possible to exaggerate this development. Royal authority certainly diminished in the late Middle Ages, but factionalism was hardly the principal cause. Admittedly the development in its place of strong local lordships centered around the earldoms of Kildare, Ormond, and Desmond led to intense competition for control of the office of chief governor. From 1414, there was a prolonged struggle for political power between the earl of Ormond and the Talbot family. When the Wars of the Roses gripped England from the 1450s, the opposing houses of Lancaster and York became identified in Ireland with the earls of Ormond and Kildare, respectively. This Geraldine-Butler feud continued into the early modern era. However, the intricacies of these various conflicts have only casually been studied, and we should be cautious about attributing to them the “decline” of English lordship in Ireland. The great lineages survived in frontier conditions by employing unorthodox but expedient methods. Their private armies and networks of power admittedly could be used for destructive purposes, both against each other and against the administration. However, although they were technically illegal, it was arguably these methods that ensured their survival and contributed to the endurance rather than decline of English control over much of Ireland.

Bastard Feudalism

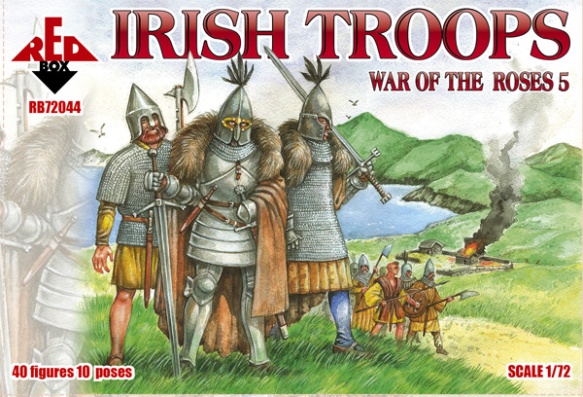

It should be remembered that Ireland’s incorporation into the feudal system occurred extremely late in the development of feudalism as a whole. Almost from its inception, therefore, the new lordship displayed signs of what historians have labeled “bastard feudalism.” If any term has generated more debate than feudalism among historians of recent decades, it is surely its supposedly illegitimate successor. Bastard feudalism, so-named in the late nineteenth century, refers to a relationship between lord and man based on money pensions and a written contract rather than land. An older school of historians dated this “perversion” of the feudal system to the reign of King Edward III and the start of the Hundred Years War in the fourteenth century. They blamed it for disorder, violence, and, most extravagantly, for the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485). The Irish evidence supports more recent scholarship that has pushed the chronology further back until we must question if there was ever a purely feudal age. It seems likely that in Ireland, from the moment of English involvement, the clear feudal hierarchy was supplemented by less well-defined expediencies. The lord of Leinster, William Marshal (d. 1219), brought his bastard feudal affinity with him to Ireland in the early 1200s. Indeed, a society like Ireland, where warfare was endemic, was ideally suited to such developments. Lords on the frontiers required their own private armies if they were to hold on to their conquests. Edward I exploited this to the full in the late 1290s when he contracted armies from Ireland to serve in his attempted conquest of Scotland. So valued were these levies that the “Red earl” of Ulster was able to negotiate with the king for the highest pay awarded any earl in the campaign.

A related factor immediately apparent in Ireland and traditionally associated with the “decline” of feudalism is the growth of liberty jurisdiction, under which lords were given powers akin to those of the king within a specific region that had its own administration and courts. At the time of the initial invasion, Leinster, Meath, and Ulster were all created as liberties, and from the fourteenth century the earls of Kildare, Ormond, and Desmond all personally controlled liberties. These liberties are traditionally seen as encouraging factionalism between “over-mighty” subjects. However, given the weakness of royal government in Ireland, it was quite possibly the creation of paid private armies and the power conferred by liberties that ensured the endurance of English control over much of the country.

These are subjects that have been largely neglected since A. J. Otway-Ruthven first examined feudal institutions in Ireland in the 1950s, and the time is ripe to bring current research on late medieval society into an Irish context. The importance of doing so may lie in the fact that so-called bastard feudal connections straddle the two cultures of medieval Ireland. The Gaelic lords may have rejected what we think of as classic feudalism, but the student of bastard feudalism would find the private armies of Gaelic lords, particularly the mercenary galloglass who dominate the military history of the late medieval lordship, surprisingly familiar. From the second half of the fourteenth century onward, the records of the earls of Kildare and Ormond are littered with agreements of retinue between Anglo- Irish and Gaelic lords. Testament to the success of the system is its endurance to the end of the medieval period. The power network of the earls of Kildare – which criss-crossed the cultural frontier – was a challenge to the authority of the Tudor monarchy and provoked a show of unprecedented strength by Henry VIII to bring it down.