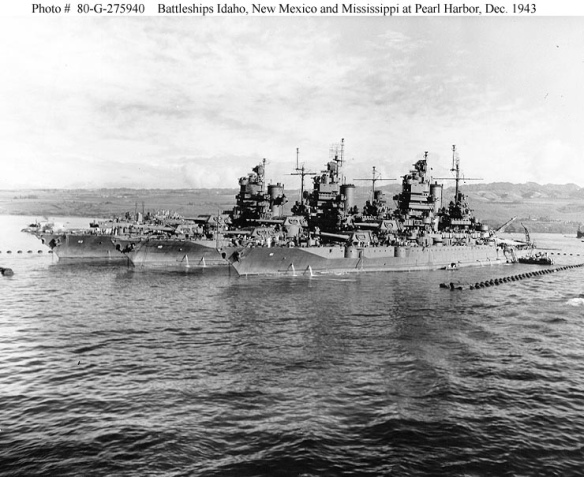

Battleships Idaho, New Mexico, and Mississippi at Pearl Harbor, December 1943.

The U.S. Navy battleship USS Tennessee (BB-43) underway in Puget Sound, Washington (USA), on 12 May 1943, after modernization.

The first units of the New Mexico class (New Mexico, Mississippi, and Idaho) were all laid down in 1915 and could operate at 21 knots. Only Mississippi saw active service in World War I, but like the other U.S. Navy dreadnoughts, it never fired a main gun in anger during that conflict. The follow-on California class (California and Tennessee) were laid down in 1916 and 1917. The succeeding Colorados generally resembled the New Mexicos except for their eight 16-inch main guns. Both classes’ turbines could turn out a speed of 21 knots.

The eight units of the New Mexico/Tennessee/Maryland class may be considered as among the most graceful warships of the dreadnought era. With their nearly unique clipper bows and trim lines, particularly after their cumbersome lattice (or wastepaper basket) masts were finally removed by the late 1930s, they made their predecessors look positively lumbering. The first three units of this class were the last U.S. Navy battleships to carry secondary guns in the hull; these positions were soon plated over in the interests of watertight integrity. The remaining units carried no such problematic weapons.

Idaho and Mississippi retained direct turbine drive, but the remaining units expressed the U.S. enthusiasm at the time for electric propulsion (which was also applied to motorbuses in a few U.S. cities). Electric drive had been pioneered on a lowly collier, USS Jupiter (later converted to the U.S. Navy’s first carrier, Langley). In this type of marine propulsion, two turbines were directly connected to two 4,242-volt, two-phase generators, which in turn fed four 5,200-kilowatt, slow-turning motors directly coupled to the propeller shafts in place of gearing. With electric drive, warships could dispense with the separate reverse turbine, would enjoy greater watertight subdivision (the turbogenerator did not have to be directly connected to the drive shafts), and all screws could be operated even if one generator failed. But the electric drive’s disadvantages were serious: greater expense, dangerous high-voltage cables throughout the hull, vulnerability to moisture and battle damage, and heavier weight and lower efficiency than direct-turbine plants of comparable power. After the New Mexicos/Tennessees/Marylands, no other battleships of any nation used this propulsion method. Still, it should be noted that the electric propulsion system in this class gave little trouble throughout the warships’ long service lives.

New Mexico, Mississippi, Idaho, Tennessee, and California mounted 12 14-inch, caliber .50 heavy guns in four turrets (three guns to each turret). But Colorado, Maryland, Washington, and West Virginia carried the new 16-inch, caliber .45 heavy guns pioneered by the Japanese. The main battery of eight guns was carried in four turrets, two guns per turret. The class had the same armor arrangement and thickness as the preceding Nevada class. Construction on Washington was halted under the terms of the Washington Treaty of 1922, when the unit was more than 75 percent completed; it was expended as a target vessel in 1924. The first four units of the class carried a single trunked funnel; the remainder could be distinguished by their two separate funnels.

The first three units of the class received new engines and boilers in the mid-1930s, and the remainder underwent extensive reconstruction in the wake of Pearl Harbor. California and West Virginia were sunk at Pearl Harbor (California probably more through poor damage control than because of Japanese ordnance), and both were raised. Tennessee was hit by two bombs and suffered moderate damage. All battleships of this class were extensively modernized for World War II service, and their new compact upperworks bore a strong resemblance to those of later U.S. battleship classes and the Royal Navy re-built King George class. The class was used, like its predecessors, for coastal bombardment and convoy duties, although California, Maryland, and West Virginia also fought at Surigao Strait. Run almost to exhaustion during World War II, the class may be considered the finest example of the battleships completed before the Washington Treaty.