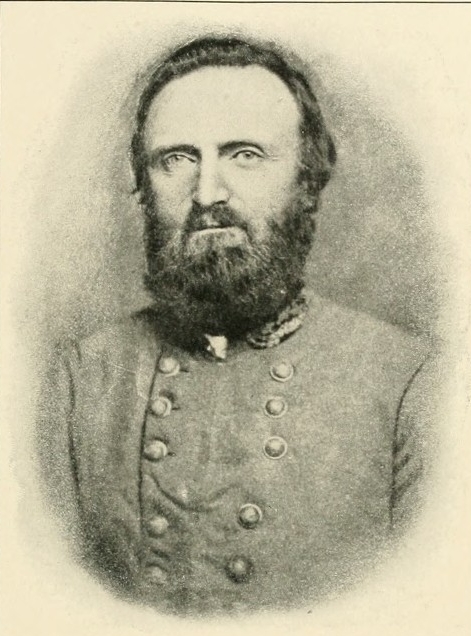

“General Lee was the handsomest man I ever saw. John C. Breckinridge was a model of manly beauty, John B. Gordon, a picture for the sculptor, and Joe Johnston looked every inch a soldier. None of these things could be said of Jackson.” LIEUTENANT HENRY KYD DOUGLAS, AIDE TO GENERAL THOMAS J. JACKSON

• Lieutenat-General Thomas J. Jackson • General Robert E. Lee • Major-General J. E. B. Stuart

The 1st Virginia Brigade, encamped on a farm not far from the stream called Bull Run, lined up in close column on the morning of November 4, 1861. The 1,800 men present snapped to attention and stood waiting for long moments. Nothing moved but their bullet-torn battle flags, stirring a little in the light breeze.

Then into the grassy clearing ambled a small, scruffy sorrel horse of dubious pedigree and uncertain gait, carrying a rider whose disreputable appearance belied his only adornments-the stars and wreath of a general. His coat was a faded relic from the Mexican War era. The visor of his shapeless cap was pulled far down, shadowing the grim, bearded face and concealing the blue eyes that took on a feverish glitter in the frenzy of battle. He sat his horse awkwardly, torso bent forward as if leaning into a stiff wind, legs akimbo in flop-top boots, and gigantic feet (estimated at size 14 although he was only 5 feet 10 inches tall) thrust into shortened stirrups.

The general reined the little horse to a halt and prepared to address the silent ranks. He disliked speaking before large groups and was poor at it. For a decade before the War he had lectured as a professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy and as an instructor of Artillery Tactics at the Virginia Military Institute. His classes had been notorious for their sedative quality. He had once been overwhelmed by embarrassment when, as a deacon of his Presbyterian church in Lexington, he had been called upon to lead prayers. Yet as he addressed the brigade that bore his nickname, Stonewall, he spoke with a certain stiff eloquence.

“Officers and men of the First Brigade,” he began in his high-pitched voice. “I am not here to make a speech but simply to say farewell. I first met you at Harpers Ferry in the commencement of the War, and I cannot take leave of you without giving expression to my admiration of your conduct from that day to this, whether on the march, in the bivouac, or on the bloody plains of Manassas. I shall look with great anxiety to your future movements, and I trust whenever I shall hear of the First Brigade on the field of battle it will be of still nobler deeds achieved and higher reputation won.”

The general stopped as if done. Then, caught by a surge of emotion, he flung his reins on the sorrel’s neck, rose in his stirrups and stretched out his right hand in the gesture of Joshua.

“In the Army of the Shenandoah,” he cried, “you were the First Brigade; in the Army of the Potomac you were the First Brigade; in the Second Corps of this army you are the First Brigade; you are the First Brigade in the affections of your General; and I hope by your future deeds and bearing you will be handed down to posterity as the First Brigade in our second War of Independence.

“Farewell!”

Then Major General Thomas Jonathan Jackson wheeled Little Sorrel and, followed by wild yells from the men, started his journey to his new command in the great Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

“If this Valley is lost,” Jackson once insisted in a letter to a friend, “Virginia is lost.” And it was widely believed that if Virginia were lost, the Confederacy would perish. Whatever the validity of these surmises, the Shenandoah was of vital strategic import to both sides, and politicians in Washington as well as Richmond were poignantly aware of that fact.

In Confederate hands, the Valley was a salient thrusting into the Union’s eastern front; terminating on the Potomac 30 miles northwest of Washington, the Valley flanked the capital menacingly. So long as the Shenandoah Valley was controlled by Confederate forces. Federal authorities in Washington, Maryland and even Pennsylvania would remain restless and apprehensive of their security.

If the Valley were to fall into Federal hands, Confederate troops in the Piedmont region east of the Blue Ridge Mountains would stand in constant danger of attacks through the 11 passes from the Shenandoah. In the Valley’s southern reaches, a Federal force in control of Staunton would threaten the crucial Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, which ran from Richmond to the Mississippi River. Indeed Richmond itself would be imperiled, and the cornucopia of foodstuffs produced in the Valley would be denied to the Confederacy.

Keeping the Shenandoah for the Confederacy and exploiting it as a threat to the Union would be Jackson’s mission for the next eight months of his life. On the scale of campaigns in the Civil War, his Valley Campaign would be minuscule; his puny army would never number more than 17,000 men, and its few pitched battles taken together would not compare in size or casualties with such major clashes as Seven Pines or Shiloh. The campaign was basically a grueling series of maneuvers in which Jackson, driving his men until their feet bled, led the Federals on one wild-goose chase after another. In one period of 48 days on the march, his men covered 646 miles.

Yet for the very reason that it succeeded brilliantly without costly battles, the Valley Campaign enshrined Jackson as one of history’s great captains. It demonstrated dramatically the powerful strategic influence that small armies, operating on the enemy’s flank and threatening his rear, can exert on major theaters of war. The shattering blows delivered by Jackson in the sequestered Valley of the Shenandoah had the effect of temporarily paralyzing the 120,000 Federals McClellan was preparing to send against Richmond and eventually diverting 40,000 troops from the offensive. Thanks largely to this diversion, the Confederacy’s vital communications center was saved, and the course of the great conflict prolonged.

These accomplishments astonished friend as well as foe, and all the more so because they were the work of an eccentric often dismissed as “Fool Tom.”

After his stirring farewell to the 1st Virginia Brigade near Bull Run on November 4, Jackson set out for Winchester to take charge of Confederate forces in the Shenandoah. With two aides he rode about five miles to Manassas Junction, where they boarded a train heading west through the Manassas Gap in the Blue Ridge Mountains. After descending into the Shenandoah Valley, the train passed through the town of Front Royal, and 10 miles later skirted the northern end of Massanutten Mountain, which roughly parallels the Blue Ridge for 45 miles. At dusk Jackson and his aides finally reached the little town of Strasburg. Despite the late hour and the wearying train ride, Jackson refused to spend the night there. His party started north on horseback and covered the 18 miles to Winchester before midnight.

In all of the Shenandoah Valley, no place was to be fought for more fiercely and frequently than Winchester, the pleasant little colonial town that was, among other things, the hub for nine important roadways. Confederate control of Winchester offered the inviting possibilities of invasions into Maryland or Pennsylvania, or a movement against Washington; it also provided a base for raids against the B & O. Conversely, Federal occupation of Winchester would provide a staging area for incursions up the Valley, enhance the security of the Union’s territory and promise greater protection for the B & O. As an astounding consequence, Winchester would change hands no fewer than 72 times during the War.

It was there, early on the morning of November 5, 1861, that General Jackson established his headquarters and notified Richmond that he had taken command.