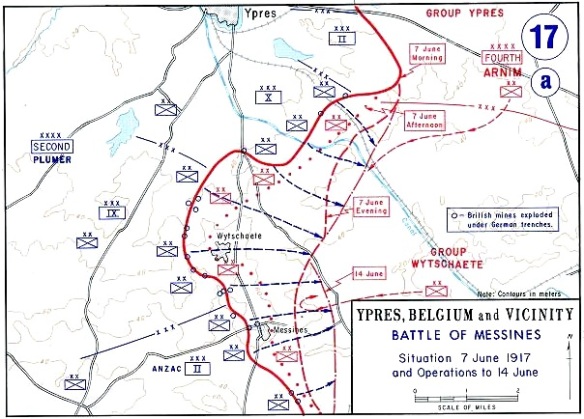

Map of the battle, depicting the front on 7 June and subsequent action until 14 June.

After the debacle of Arras, Allied attention turned to Haig’s long-awaited Flanders offensive. The final splutterings of the Arras offensive had been diversionary in nature, fought to deflect attention from both the problems of the French and the burgeoning preparations already being started in Flanders. But now underpinning everything was the necessity to focus German attention on the BEF and thereby allow the French Army more recovery time. Before any operations to clear the Ypres Salient could begin it was necessary to push the Germans back from their positions on the ‘heights’ of the Messines Ridge to the immediate south. Preparations had long been underway, by General Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army, and since 1915 an incredible series of deep-driven tunnels had been burrowed under the ridge and filled with explosives. Early in 1917, the process had been accelerated in anticipation of the attacks planned to capitalise on the promised success of the Nivelle offensive. The planning for the Flanders offensive was dogged throughout by the necessity of choosing between the ‘bite and hold’-style approach with restricted objectives and the natural desire to maximise possible gains to capitalise on the enormous allocation of resources represented by such an offensive. Plumer in particular was inclined to restrict his horizons initially to just the Messines and Pilckem Ridges; this was not enough for Haig, who preferred a more ambitious agenda with built in contingency plans to maximise potential gains. Seeking a more aggressive approach than that offered by Plumer, Haig selected General Sir Hubert Gough to command the main Ypres offensive, while Plumer commanded the opening assault on Messines Ridge. There would, however, still be a delay of some weeks after Messines as the artillery were moved northwards to amass in front of Ypres. The original plan was that the BEF attack would be supported by a parallel French attack, but this had to be abandoned when the mutinies proliferated across the French Army. Haig would have to go it alone, which meant that the Germans too would be free to concentrate all their attentions on Flanders. This may have benefited the weakened French but it promised pain and suffering for the BEF.

The Messines plans produced by Plumer represented another high point in the development of the ‘bite and hold’ tactics. There would be a 4-day barrage followed by the intended detonation of twenty-one mines containing a million pounds of high explosive underneath key German defensive positions all along the length of the ridge. Plumer originally planned an advance of only 1,500 yards but Haig, not unnaturally in view of the almost incalculable expenditure of valuable military resources, wanted to attempt both the seizure of the German second line at the back of the ridge and the Oosttaverne Line on its rearward slopes. All together this would entail a total advance of some 3,000 yards. To achieve this Plumer had been given nine assault divisions, with three more as a reserve force. In all he had a total of 2,266 guns of which 1,510 were field artillery and the rest were the heavy artillery required to take on the German batteries and destroy reinforced concrete strongpoints. In the preliminary bombardment 3,561,530 shells were fired. The plans for the creeping barrage to protect the advancing troops were also gaining in complexity, for it was now mixed with barrages directed at a sequence of identified strongpoints further ahead of the troops. Once these objectives had been achieved the creeping barrage would then settle as a standing barrage just ahead of the new lines in order to protect them from the inevitable German counter-attacks. The infantry would be accompanied in their attack by some seventy-two tanks, while throughout the attack the massed Vickers machine guns of the Machine Gun Corps would be firing over their heads spraying millions of bullets over the target areas. But the eye-catching innovation was the sheer size of the mines. Captain Oliver Woodward of the 1st Australian Tunnelling Company was on tenterhooks as he waited to detonate his mine under Hill 60.

I approached the task of final testing with a feeling of intense excitement. With the Wheatstone Bridge on an improvised table, I set out to check the leads and as each one in turn proved correct I felt greatly relieved. At 2.25 am I made the last resistance test and then made the final connections for firing the mines. This was a rather nerve-racking task as one began to feel the strain and wonder whether the leads were correctly joined up. Just before 3 am, General Lambart took up his position in the firing dugout. It was his responsibility to give the order, ‘Fire!’ Watch in hand, he stood there and in a silence that could almost be felt he said, ‘Five minutes to go.’ I again finally checked up the leads and Lieutenants Royle and Bowry stood with an exploder at their feet ready to fire should the dynamo fail. Then the General, in what seemed to be interminable periods, called out, ‘Three minutes to go!’ ‘Two minutes to go!’ ‘One minute to go!’ I grabbed the handle firmly and in throwing the switch over my hand came in contact with the terminals, so that I received a strong shock that threw me backward. For a fraction of a second I failed to realise what had happened, but there was soon joy in the knowledge that Hill 60 mines had done their work.

Captain Oliver Woodward, 1st Australian Tunnelling Company, AIF

The explosion was cataclysmic – and even before the ground had settled the massed British artillery had burst into life.

Never could I have imagined such a sight. First, there was a double shock that shook the earth here 15,000 yards away like a gigantic earthquake. I was nearly flung off my feet. Then an immense wall of fire that seemed to go halfway up to heaven. The whole country was lit with a red light like in a photographic darkroom. At the same moment all the guns spoke and the battle began on this part of the line. The noise surpasses even the Somme; it is terrific, magnificent, overwhelming. It makes one almost drunk with exhilaration and one simply does not care about the fact that we are under the concentrated fire of all the Hun batteries. Their shells are bursting round now as I write at 3.40am, but it makes one laugh to think of their little efforts compared to the ‘Ausgezeichnete Ausstellung’ that we are providing. We are getting our revenge for 1914 with a vengeance.

Major Ralph Hamilton, Headquarters, 106th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

For the Germans the impact of the massive explosions was incredible.

The earth roared, trembled, rocked – this was followed by an utterly amazing crash and there, before us in a huge arc, kilometres long, was raised a curtain of fire about one hundred metres high. The scene was quite extraordinary; almost beyond description. It was like a thunderstorm magnified one thousand times! This was followed by thousands of thunderclaps, as the guns opened up simultaneously, adding their contribution to the power just unleashed. The wall of fire hung in the air for several seconds, then subsided to be replaced by the flashes of the artillery muzzles, which were clearly visible in the half light. For an instant we just stood, mesmerised by the spectacle. There was no question of returning to the rear to have wounds dressed, because hardly had the wall of fire died away to nothing than the entire earth seemed to come to life. Scrabbling their way forward from hundreds of starting points came steel-helmeted men. Line upon line of infantrymen emerged and the enemy launched forward.

Second Lieutenant Meinke, 176th Infantry Regiment

The infantry went over the top, sweeping over the utterly shattered German front line positions on the forward crest. After a short pause they moved on at 07.00, with the battalions leapfrogging to maintain the impetus of the assault. The Germans were unable to hold them and Haig was proved right as his men pushed through to take the fortified village of Wytschaete by 09.00. After a further break to re-organise, the infantry began to attack the reverse slope positions at 15.10. By this time they were beyond the range of the British field artillery and, without the massed support of the guns, casualties began to increase sharply. Even so, the Oosttaverne Line was safely in British hands before the end of the day. Subsequent painful tidying-up operations would finally succeed in attaining all the British objectives within the week, although they suffered a total of 24,562 casualties during the battle as a whole. None the less the Battle of Messines was a triumph for Plumer. His methodical tactics had overwhelmed a strong German fortress in a key location with the capture to boot of 7,354 prisoners, 48 guns, 218 machine guns and 60 mortars. With the Messines Ridge under British control the way was open for Gough’s assault on the German lines that almost encircled Ypres.