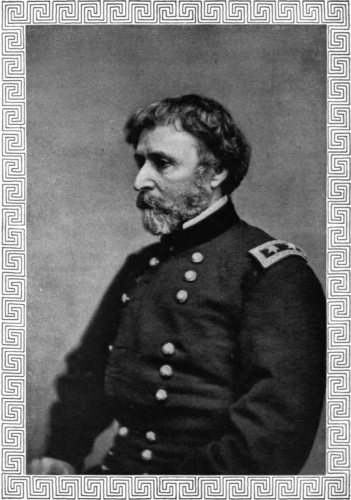

Major General John Charles Fremont

As war came to Missouri, the overall Federal command in the West passed to a nationally known figure, Major General John Charles Fremont. At the age of 48, Fremont was a volatile, rather romantic man who had made a glamorous reputation for a series of expeditions that mapped the Oregon Trail and the California Trail. In 1856, he had been the first presidential nominee of the Republican Party. He owed his new command partly to Congressman Frank Blair [the fiery organizer of Missouri’s Unionists] whose first choice, Lyon, had been vetoed by Washington because the fierce little general had outraged so many moderate Missourians.

Opposing Fremont as the senior Confederate commander was 55-year-old Major General Leonidas Polk. Trained at West Point-where Jefferson Davis was his friend and classmate-Polk had subsequently taken religious orders in the Episcopal Church and risen to become Bishop of Louisiana. Although Polk was highly regarded by the government in Richmond-President Davis had personally called him back into service- he was thought by some professional military men to be a textbook general who lacked drive and flair.

Fremont and Polk had a good deal in common. Both men were only marginally competent as commanders. Both railed at the shortage of weapons and supplies, complaining that their governments satisfied the needs of the Eastern campaigns first and sent them whatever was left over. The troops they received were-as Fremont griped to the War Department-“entirely unacquainted with the refinements of military exercise.” Here, as in the East, the commanders were faced with an enormous training problem. Well-disciplined troops, such as the Federal Home Guard and the Confederate force under Ben McCulloch, were rare exceptions. Until large numbers of the green recruits on both sides could be instructed in the essentials of weaponry and hammered into a semblance of functional regiments and brigades, no large-scale, formal offensive was possible in the West.

In the meantime, the small-scale, irregular war in Missouri picked up momentum as General Lyon’s Federals headed south in pursuit of General Price and Governor Jackson. In Lyon’s command was a detachment of 1,250 Home Guards led by Colonel Franz Sigel. The colonel was an intense professional soldier who had left his native Germany after fighting with distinction in the failed revolution of 1848. A strict disciplinarian, he had relentlessly drilled the Guardsmen to prepare them for combat. They were thoroughly versed in formation movements, gunnery and small-arms drill.

The Germans had an important role in Lyon’s campaign plan. His idea was to detach them from his main force and send them south by rail as part of a 2,500-man expedition to cut off Jackson’s retreat toward Arkansas. Reinforced by volunteers who joined him as he marched, Jackson now had about 2,600 infantry, plus the 1,500 cavalry troops brought in by Jo Shelby. If this considerable force could be blocked, Lyon and his main force would have time to come up and attack them from the rear.

The brigade took a train to the rail terminus of Rolla, then marched 125 miles southwest to Springfield. There Sigel left the main body, taking 1,500 of his Germans to reconnoiter as far as the Arkansas fine. Returning, he encamped a mile southeast of Carthage on the evening of July 4 and sent his commissary officers into town to arrange for supplies. The officers returned with the exciting news that Governor Jackson was 10 miles to the north and getting ready to move into the town of Carthage.

Sigel knew that he was outnumbered by more than 2 to 1, but he also knew he had no time to send for reinforcements. He gave orders to march against Jackson before dawn. The two forces met nine miles north of Carthage-at a point where the prairie descended in a long, gentle slope to a belt of trees skirting Corn Creek and then rose again to a well-rounded ridge. Jackson and his senior officers were confident in their superior numbers and content to wait on the northern ridge while the Germans descended the opposite slope and crossed through the trees.

As the Germans emerged from the woods, they deployed in column of companies to forestall any flanking movement by cavalry- a precision maneuver that the raw Confederates watched with admiration. At 700 yards, Sigel’s artillery opened fire, and the Confederate artillery replied.

After an hour of ineffectual artillery dueling, the Federal infantry surged forward in line of battle behind such accurate rifle fire that the center of the Confederate line showed signs of buckling. But then Confederate cavalrymen swept away to the south and disappeared into the woods at the rear. The cavalry made no attempt to attack the well-defended Federal right or left flanks, but Sigel became worried that he might be cut off from his lumbering wagon train. He ordered a retreat under fire. His men carried out that famously difficult maneuver with brilliance, moving their cannon back one by one in a sort of leapfrog movement to provide covering fire for the infantry.

It was an inconclusive little battle with not many casualties-the Federals lost 13 killed and the Confederates 10. But it served as a temporary check to the fleeing Confederates, and it raised Lyon’s hopes that he would eventually be able to catch and destroy them. In addition, it was richly instructive to the local Confederate commanders, who saw for the first time the importance of formal training. When news of the battle and the Germans’ maneuvers reached Price, he realized that the need for seasoned troops to support Jackson was even more urgent than he had thought. He hastened on south toward his rendezvous with McCulloch.

Price’s command grew as he went. From Missouri’s farms, forests and villages, recruits by the hundreds came swarming to join Pap’s crusade. He would take only those who brought their own horses. The rest he told to wait for Governor Jackson, who would be passing with his infantry columns in a few days’ time.

Price’s efforts to train and outfit his growing force seemed doomed to fail. The farm boys and backwoodsmen who streamed into his command as he moved south were irregular and ill equipped in every way. The weapons they carried ranged from shotguns and squirrel rifles to ancient flintlock fowling pieces. None of them had uniforms or tents or supplies. They made their own ammunition, using lead from southern Missouri mines and molds fashioned from green hardwood. “My first cartridge resembled a turnip,” recalled a recruit-but soon, he added, his unit’s homemade ammunition looked almost professional. One-inch slugs cut from iron rods or old chains furnished the artillery with canister, and smooth stones took the place of solid shot. However, the troops had no waterproof cartridge boxes, and since water would ruin their paper cartridges, they were unable to march in rainy weather.

This motley force slowly rambled southward, bivouacking in the open, living off the land and foraging the horses on prairie grass. By the time Price got to southwestern Missouri, he had 1,200 men; his command increased to 7,000 men on July 7, when he met and took over Jackson’s infantrymen. Nearly a third of the men were without weapons; they were told to arm themselves in battle by the gruesome but practical procedure of following on the heels of their armed comrades and seizing weapons from the hands of the dead and dying.

On the 29th of July, 23 days after the Carthage battle and about 40 miles to the southeast. Price linked up with the little army of Ben McCulloch. Price was disgusted to find that the Texan was a vain, flamboyant man who wore a velvet suit with flowing swallowtails. McCulloch in turn deprecated Price as “nothing but an old militia general” and cast grave doubts on the fighting ability of Price’s “half-starved infantry” and “huckleberry cavalry.” But now at last, with a joint command of 14,000 men, including some last-minute reinforcements, the Confederate leaders had strength to attack Lyon.

In fact, Lyon was in poor and worsening shape. His effective force was rapidly dwindling to less than 6,000 as the enlistment period of 90-day volunteers came to an end and many returned home. And while pursuing Price, Lyon had seriously overextended himself. He had moved a full 120 miles beyond the railroad at Rolla, his only dependable source of supply, and was camped near the town of Springfield, Missouri, roughly 50 miles north of the Price-McCulloch rendezvous.

Price wanted to attack Lyon immediately, but McCulloch flatly refused to put his troops under Price’s command. Price, desperate to destroy Lyon’s army and swing Missouri to the Confederacy, confronted McCulloch in a stormy session and offered to give him the command if he would agree to attack. On that understanding, the merged forces moved north. They went into camp at Wilson’s Creek, about 10 miles from Springfield; McCulloch picked the spot because nearby fields of ripening corn could feed his ragged army.

Lyon realized he was in a difficult spot. He knew that the Confederates were preparing to attack him, and that they outnumbered him by more than 2 to 1. On the other hand, he could scarcely retreat, for he had virtually no cavalry to protect his straggling column from the blows of the Confederate mounted troops.