Known to history as the ‘March of the Ten Thousand’, the Greek mercenaries’ return to friendly territory imparted and reinforced some valuable tactical lessons about the uses and limitations of Greek heavy infantry and the importance of utilizing light troops in rough terrain. Like the battle of Sphacteria in 425, the Greeks were obliged to fight under unfamiliar and mountainous conditions on their march, and consequently, the role of light infantry was enhanced. When attacked from above by enemy guerrillas, a contingent of Cretan light infantry peltasts was used to control the high ground until the hoplites marched past, then moved along the higher elevations to repeat the manoeuvre while an advance guard secured the next ridge. In the words of a commander present on the march upriver, the brilliant young Greek general Xenophon (c.428–354 bce), writing about himself in the third person:

-Whenever the enemy got in the way of the vanguard, Xenophon led his men up the mountains from the rear and made the road-block in front of the vanguard ineffectual by trying to get on to higher ground than those who were manning it … So they were continually coming to each other’s help and giving each other valuable support.

The role of light infantry in the retreat upriver was so important that the Rhodian contingent of heavy infantry were asked by Xenophon to put down their aspides and come forward and exercise their native skills as light infantry slingers.

The march to Cunaxa as a part of the Persian train showed the Greek leadership the effectiveness of the Persian supply system, while the ‘March of the Ten Thousand’ from Cunaxa upriver to the Black Sea imparted valuable lessons in combined arms and logistics to the Greeks. The logistical problems suffered by the Greeks on their return journey convinced them of the necessity of organized supply. But perhaps most importantly, the lessons learned were shared with other Greek commanders, chiefly through the writings of Xenophon. He spent the next several decades analysing the lessons of military action against the Persians, and his accounts influenced the leading military figures of his age.

The lessons of the Peloponnesian War and the Persian Expedition were not lost on Greek battle captains. In fact, such experiences led to the development of the first true military science in western civilization, a tacit recognition that warfare had become complicated in the classical world, and that the martial contacts between Greece and the Near East necessitated the implementation of more systematic modes of warfare. The Greek military revolution in the first half of the fourth century bce was a response to this recognition. This military revolution has been characterized as the co-ordination of ‘the infantry of the West with the cavalry of the East’, a valuable appraisal, but one which fails to appreciate the sophisticated nature of the martial exchanges between Greece and the Near East.

The military revolution of the fourth century bce involved invention and diffusion and adaptation of both ideas and technologies. Before the Greeks and the Macedonians could penetrate the heart of Persia in 336 bce, they needed to create a well-articulated combined-arms tactical system including heavy and light infantry, skirmishers, and heavy and light cavalry, as well as learn the means of supporting such forces logistically. Besides creating an integrated army, Alexander would require an efficient siege train to storm the highly fortified strongholds of the Levant. Each of these elements was inherited by the young Macedonian king from developments which took place all over the Greek world in the previous two centuries.

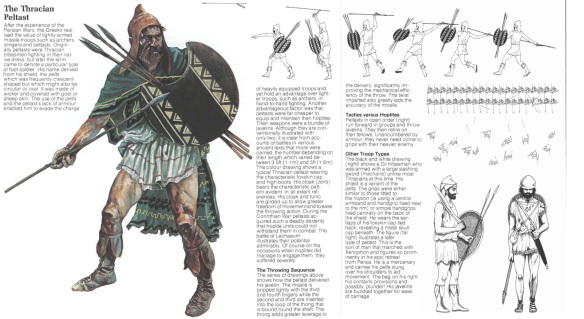

With the increasing complexity of Greek warfare, the study of proper generalship developed into a required science and gave rise to the emergence of ‘professors’ of tactics. Mercenary commanders such as Xenophon, Iphicrates (c.412–353 bce) and Chabrias (c.420–356 bce) translated their experience on the battlefield as generals into treatises on tactics. The appearance of these professors indicates a change in how warfare was viewed by Greek society. Warfare emerged from the realm of morality and honour to become something more than a way of life to be conducted according to ancestral expectations. As the idea of combined arms gained acceptance in Greek society, there was a switch in emphasis from the traditional to the innovative, with a necessary by-product being an escalation in the diffusion of tactics and the invention of improved weapons and armour.

As the Greeks began to experiment with light infantry, cavalry and skirmishers, the age of hoplite-dominated warfare came to an end. But Greek heavy infantry would experience a brief resurgence during the wars of shifting hegemony in the 370s and 360s bce with the wars between Thebes and the Peloponnesian powers of Sparta and Mantinea. After thirty-three years of sporadic warfare, Athens and Sparta agreed to peace terms in 371 bce. The third member of the truce talks, Thebes, insisted on signing on behalf of all of Boeotia. This position by the Theban leader, Epaminondas (d. 362 bce), caused the negotiations to break down, forcing the Spartans to march into Boeotia to punish the Thebans. The resulting battle of Leuctra in 371 pitted the finest Greek heavy infantry armies against one another for regional supremacy.

The Spartans, commanded by their king Cleombrotus, camped to the south of the flat plain of Leuctra on a ridge of hills facing the Thebans, who were also on a ridge across the plain to the north. Epaminondas arranged his 6,500 heavy infantry, 1,000 peltasts and 1,500 cavalry in an oblique formation, weighing his left wing with an extended phalanx at least 50 ranks deep (led by the elite group of homosexual hoplites known as the ‘Sacred Band’), while refusing his right wing. Here the Theban general broke with tradition by placing his best hoplites across from the Spartans instead of on the right wing, the normal place of honour in Greek warfare. Epaminondas was seeking a decisive battle, one that would break the back of Spartan power in the region. The Spartans arranged their 10,000 heavy infantry, 1,000 cavalry and 1,100 light troops in a concave position, placing their hoplites in the traditional line twelve men deep. Although they were heavily outnumbered, Epaminondas spurred his men forward across the plain, using his cavalry to screen his weighted left wing.

On the Theban left wing the cavalry drove back the Spartan horse. While the Theban cavalry prevented outflanking, the heavily reinforced Theban phalanx crashed into the Spartan right wing, driving the invaders back and killing the Spartan king Cleombrotus and perhaps 500 hoplites and light troops (Map 2.7(b)). The Spartan left wing routed before ever seeing action. As many as 300 Thebans were killed. The unorthodox use of a weighted wing gave the outnumbered Thebans a great victory over the best army in Greece. The battle of Leuctra shattered the military prestige of Sparta and ended its chance of establishing hegemony over Greece.

Nine years later, at the battle of Mantinea in 362 bce, Epaminondas fought a confederation of Greek city-states challenging Theban hegemony in the region. Once again, Epaminondas defeated his enemies using an oblique formation and a left wing weighted with a deep hoplite formation. And once again, heavy infantry proved to be the decisive arm in the battle, crashing through the thin ranks of the enemy’s line and precipitating a rout. But Epaminondas’ untimely death on the battlefield disheartened the Thebans, who gave up their pursuit of the enemy and lost the initiative. After his death, Theban political fortunes declined, leaving a power vacuum for the rising hegemon of Macedon to exploit.

In the first half of the fourth century bce, both the Greeks and the Persians made new attempts to apply the lessons learned from their previous battlefield encounters. The introduction of light infantry to Greece during the Peloponnesian War destroyed the dominance of the hoplite, while the diffusion of the articulated heavy infantry phalangeal formation to the Near East gave Persian battle captains another instrument for shock combat. The major difference between the two diffusions lay in how they were applied to warfare in each civilization. Consequently, the art of war in the classical world evolved with the Greeks’ elevating it to a science through the introduction of professors of tactics, and later, under Macedonian leadership, the adoption of articulated heavy cavalry and the improvement of the hoplite equipment. The Persians also adopted heavy cavalry but failed to discard the anachronistic chariot. Hence, the Persians created a combined-arms tactical system consisting of heavy and light infantry, and heavy and light cavalry, but their reliance on chariots as a shock component on the battlefield proved to be both foolish and wasteful. When this old model Persian army met the new model army of Alexander the Great in the fourth century bce, the battle for the largest empire the world had yet known would be won by a Greco-Macedonian force better trained, better motivated and better supplied than their Persian counterparts. The arms race in the Greek world would, ironically, be won by a state not officially within the traditional polis system. North of Greece, the kingdom of Macedon would adopt and adapt the Hellenic way of war, adding its own elements to the mix, and creating the most effective combined-arms tactical system ever fielded in the classical world.

Battle captains such as Xenophon and Epaminondas recognized the value of combined arms as a means of bringing a superior tactical system against an inferior one. The integration of light infantry archers and peltasts with heavy infantry hoplite soldiers profoundly affected Greek warfare, giving commanders additional tools to win the day. But the other elements of combined-arms warfare, heavy and light cavalry, had yet to be fully integrated into Greek warfare. With the addition of mounted shock and missile capabilities to the armies of Greece, classical warfare would reach its apogee. After the rise of Macedon, the era of phalanx-versus-phalanx warfare was never to return to the western way of war.