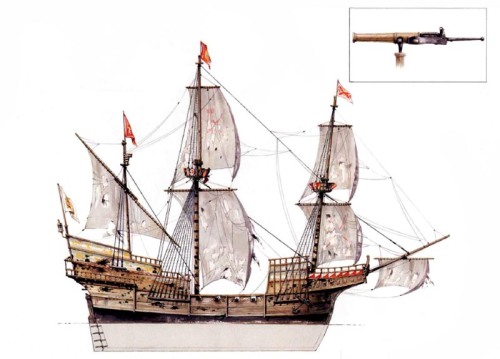

THE SAN JUAN BAUTISTA, 1588

One of 22 galleons to take part in the Spanish Armada campaign of 1588, the San Juan Bautista (one of two participating galleons bearing the same name) was the almiranta of the Squadron of Castile. She was a modern vessel with a burden of 750 toneladas, a crew of 296 men (including soldiers), and an armament of just 24 guns, excluding the smaller versos. For much of the progress of the Armada up the English Channel she was detached from her squadron, and instead formed part of an ad hoc formation of the most powerful vessels in the Spanish fleet. This ‘fire brigade’ protected the rest of the Armada formation, and consequently the San Juan Bautista participated in all of the principal engagements of the campaign. During the fighting off Gravelines (8-9 August) she was one of the four galleons which supported the fleet flagship San Martin during her legendary fight against the bulk of the English fleet, and was badly battered in the day-long engagement, her decks reportedly awash with blood. She not only survived the battle, but she subsequently managed to limp home to Spain. The San Juan Bautista was built for service in the Indies flotas, and was well built, with a relatively low profile compared to other galleons. This also accounts for her poor armament as, traditionally, Indies galleons were less well armed than those which saw regular service in the Armada del Mar Oceano. Before she sailed from Lisbon in 1588, her regular armament was augmented by the embarkation of a dozen versos of various sizes. The inset shows a verso which was recovered from the Spanish Armada shipwreck La Trinidad Valencera.

First Blood

Sunday 31 July, 9.00 am–1.00 pm: the Fleets Clash off Plymouth

Wind and Weather: wind WNW, rising; sea becoming rough

As the early morning mists cleared, Medina Sidonia saw the unwelcome sight of at least eighty-five English ships to windward of him, about 5 miles to the west of the Eddystone Rock. Other English ships, late departures from Plymouth, formed a straggling line to the north, between the Armada and the Cornish coast to within about 2 miles of the fishing village of Looe.

The Spanish commanders were probably shaken by this display of English seamanship. It had given Howard the all-important advantage of the weather-gauge, and meant that his fleet could follow their intended strategy of ‘coursing’ (harrying) the Armada up-Channel, harassing any Spanish attempt to make a landing on the English coast. Not only had the English fleet gained a vital tactical advantage by gaining the windward side of the Armada, but any lingering thoughts Medina Sidonia may have had of trapping Howard within the confines of Plymouth Sound were finally dashed.

Howard’s plan seems to have been for the ships under his own command to maintain pressure on the centre of the Spanish formation, while Drake’s and Hawkins’ squadrons attacked the potentially vulnerable tips of the horns of the lunula.

The English were overawed by their first sight of the mighty Armada. Henry Whyte, captain of the 200-ton Bark Talbot, admitted even to the formidable Sir Francis Walsingham that: ‘The majesty of the enemy’s fleet, the good order they held, and the private consideration of our own wards, did cause, in my opinion, our first onset to be more coldly done than became the valour of our nation and the credit of the English navy.’

As the English fleet approached to contact, Howard, in a chivalrous gesture that was probably entirely lost on hard-bitten privateers like Drake and Frobisher, sent the pinnace Disdain darting forward to fire a challenging shot at what he believed to be the Spanish flagship, but seems actually to have been de Leiva’s La Rata Santa Maria Encoronada. In any case, the symbolic action was hardly needed: both sides knew by 9.00 am that battle was imminent.

Spanish eyewitnesses described Howard’s attack on the centre and rear of the Armada as being made en ala (‘in file’), which has led to suggestions by some writers that the English fleet was formed in ‘line of battle’, similar to that employed by fleets at the height of the Age of Sail. This seems unlikely, as such a formation was apparently not part of recognised English tactics until almost a century later. Howard’s ships most probably made their attack in a rough echelon formation, firing their particularly heavy bow chasers as they approached, then, in a rough figure-of-eight manoeuvre, turn to fire a broadside, then their stern guns, and finally their second broadside, before retiring to reload.

The weight of Howard’s initial attack fell on de Leiva’s Rata, while Drake was heading for Recalde’s rearguard, forming the northern wing of the Armada, which could still conceivably threaten Plymouth. While the straggling English ships still coming out of Plymouth harassed the landward wing of the Armada, Howard, after his initial engagement with the Spanish centre, seems to have moved northwards to support Drake, who had about forty ships, firing as he did so at a long-range of over 400 yards.

The impact of Drake’s first assault, made by his strongest ships, which included his own Revenge and two other large Queen’s Ships, Victory and Triumph, apparently caused some panic among the naos of Recalde’s Biscayan Squadron, which veered away from the attackers towards the centre of the Armada, resulting in some confusion: while Recalde himself, who had shortened sail and turned his San Juan de Portugal broadside on to the attackers in order to bring his guns to bear, found himself temporarily alone.

Seeing Recalde under heavy fire, Medina Sidonia ordered part of his van, under de Leiva, from the unengaged right horn of the Armada, to go to the support of the San Juan, which had meanwhile been belatedly joined by Recalde’s almirante (second in command), the Gran Grin. De Leiva brought with him the Portuguese galleon San Mateo, two other galleons, and Hugo de Moncada’s four galleasses, which the English were seeing in action for the first time.

If, has been suggested, Recalde had deliberately acted as bait in order to draw Drake’s squadron to close quarters, he and de Leiva were quickly disappointed. Drake declined to fall into the trap, and pulled back, though continuing to direct an intense fire at the 1,050-ton San Juan at a range of 300 to 400 yards.

The duel continued indecisively for two hours until about 1.00 pm, with Howard providing some support for Drake. By this time, further Spanish ships, including Medina Sidonia’s San Martin, and Pedro de Valdez’ socorro (battlegroup) were also heading for the scene of action, and the battered San Juan was able to pull back into the centre of the Armada for hasty repairs. An infantry officer, Pedro Estrade, aboard the galleon San Marcos, suggests the galleasses were quick to make an impact on their opponents: ‘The vice admiral of the galleasses went putting himself into our horn of Don Pedro de Valdez, and the English, when they saw the galleasses to enter, they retired, and went away all that they could.’

As Medina Sidonia lowered his topsails in an invitation to fight, the English fleet pulled back out of range and ceased fire. The first action of the campaign was over, and as the Armada prepared to resume its formation and continue eastwards up-Channel, it was time for the opposing commanders to assess its results.

Medina Sidonia described the engagement to King Philip:

‘On Sunday, the 31st, the day broke with the wind changed to the WNW in Plymouth Roads, and eighty ships were sighted to windward of us; and towards the coast to leeward eleven other ships were seen, including three large galleons which were cannonading some of our vessels. They gradually got to windward and joined their own fleet.

‘Our armada placed itself in fighting order, the flagship hoisting the royal standard at the foremast. The enemy’s fleet passed, cannonading our vanguard, which was under Don Alonso de Leiva, and then fell on the rearguard commanded by Admiral Juan Martinez de Recalde. The latter, in order to keep his place and repel the attack, although he saw his rearguard was leaving him unsupported and joining the rest of the Armada, determined to await the fight. The enemy attacked him so fiercely with cannon that they crippled his rigging, breaking his stay, and striking his foremast twice with cannon balls. He was supported by the Gran Grin,a ship of the rearguard, and others, The royal flagship then struck her foresail, slackened her sheets, and lay to until Recalde joined the main squadron, when the enemy sheered off, and the duke collected his fleet.’

A Spanish officer, Pedro de Calderon, aboard the hulk (storeship) San Salvador, had a close view of the engagement between de Leiva’s force and Drake’s squadron, noting that the English ‘flagship’:

‘Struck her foresail, and from the direction of the land sent four vessels, one of which was the vice-flagship to skirmish with our vice-flagship [Recalde] and the rest of our rearguard. They bombarded her and the galleon San Mateo, which, putting her head as close up to the wind as possible, did not reply to their fire, but waited for them in the hope of bringing them to close quarters. The Rata, with Don Alonso de Leiva onboard, endeavoured to approach the enemy’s vice-flagship [the Revenge], which allowed herself to fall towards the Rata. But they would not exchange cannon shots, because the enemy’s ship, fearing that the San Mateo would bring her to close quarters, left the ‘Rata’ and bombarded the San Mateo. Meanwhile, the wind forced Don Alonso de Leiva away, and he was prevented from carrying out his intentions, but he exchanged cannon shots with other enemy ships. Juan Martinez de Recalde, like the skilful seaman he was, collected all his ships whilst protecting his rearguard, engaging at the same time eight of the enemy’s best ships. The duke’s flagship most distinguished herself this day, as she was engaged the greater part of the time, and resisted the fury of the whole of the enemy’s fleet.’

Lord Howard and Drake were both terse in their initial comments. Howard wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham that:

‘At nine of the clock we gave them fight, which continued until one… We made some of them bear room to stop their leaks, not withstanding we durst not adventure to put in amongst them, their fleet being so strong.’

Drake cautiously told Lord Henry Seymour, anxiously awaiting news in the Straits of Dover:

‘The 21st [31st NS] we had them in chase, and so, coming up to them, there hath passed some cannon shot between some of our fleet and some of them, and as far as we perceive, they are determined to sell their lives with blows.’

In August, writing, at rather more leisure, his official account to the privy council, Howard puts a rather more positive slant on the engagement:

‘The next morning, being Sunday, 21 July 1588 [31st NS], all the English ships that there were then come out of Plymouth had recovered the wind off Eddystone, and about nine of the clock in the morning, the lord admiral sent his pinnace, named Disdain, to give the Duke of Medina defiance, and afterward in the Ark bear up with the admiral of the Spaniards, wherein the duke was supposed to be, and fought with her till she was rescued by divers ships of the Spanish army. In the meantime, Sir Francis Drake, Sir John Hawkins and Sir Martin Frobisher fought with the galleon of Portugal, wherein John Martinez de Recalde, vice admiral, was supposed to be. The fight was so well maintained for the time that the enemy was constrained to give way and bear up room to the eastward.’

Reviewing the course of their first encounter, neither commander had grounds for total satisfaction. The English fleet had fired off a great deal of powder and shot, so much, indeed, that Howard was already calling urgently for new supplies. But firing at too long a range, they had done little harm to the Spaniards. Recalde, for example, had lost only fifteen men aboard his San Juan, which had suffered quite minor damage. As the experienced seaman Richard Hawkins once observed: ‘How much the nearer, so much the better, he that shooteth far off at sea had as good as not shoot at all.’ Howard and his commanders also had grounds for concern at their failure to break up the Armada’s formation, apart from an initial panic in Recalde’s squadron.

On the credit side, however, Howard could comfort himself with the knowledge that, if Medina Sidonia had ever intended to enter Plymouth, the morning’s fighting had carried the Armada too far east for that now to be possible. And the English retained the all-important weather-gauge.

The aspect of the enemy that had forcibly impressed itself on the Spaniards in that first encounter had been the speed and manoeuvrability of the English ships. Moving sometimes three or four times faster than their opponents, the English galleons were proving infuriatingly adept at thwarting Spanish attempts to close and board them. However, despite concern about the discipline and commitment of some of his captains, Medina Sidonia could take satisfaction in the failure of the English to penetrate his formation, or seriously damage any of his ships, despite what was obviously a much faster firing rate. He would, however, shortly have much more serious grounds for concern.