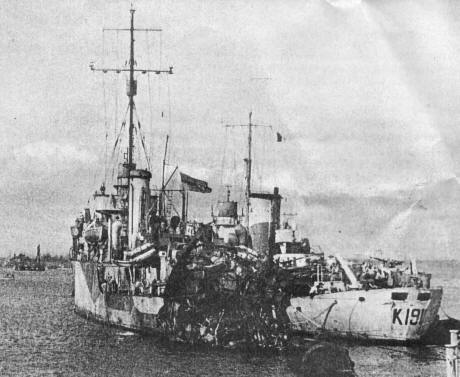

HMS Salamander after friendly fire attack – Halcyon Class Minesweeper

Massacre of the Minesweepers, 27 August 1944

Before leaving the skirmishing in the Channel, off the beaches and elsewhere, and returning to the epic destroyer battles which punctuated this period, mention should be made of one of the greatest tragedies of the Normandy landings. The attack was an aerial one and it caused heavy casualties. But it came not from the Luftwaffe, who flew very few sorties at the time, but from the RAF. The war in the Channel in 1944 showed that air/sea cooperation had not advanced one iota since the days when the RAF bombers repeatedly bombed the Newcastle and her escorts in November 1940.

On 27 August the 1st Minesweeping Flotilla was attacked by RAF Typhoon aircraft while sweeping off Cap d’Antifer. HMS Hussar and Britomart were sunk and HMS Salamander was so severely damaged as to be beyond economic repair. Two officers and forty ratings were killed in Britomart (Lieutenant Commander A. J. Galvin, DSC), three officers and fifty-four ratings were killed in Hussar (Lieutenant Commander J. Nash, MBE, RNVR) and eleven men were wounded in Salamander (Lieutenant Commander H. King, RNVR). The other ship in company, Jason, escaped without serious damage.

The flotilla had been engaged in clearing magnetic mines from the coast around Le Havre in readiness for a bombardment of that port by the battleship Warspite and monitors Erebus and Roberts, but they were switched back to the Portsmouth-Arromanches route for that Sunday only. Apparently, however, a subsequent signal ordering the ships to resume their tasks off Cap d’Antifer rather than Arromanches, where they had been chiefly employed since D-Day, was not repeated to the Flag Officer British Assault Area (Rear Admiral J. W. Rivett-Carnac). Although the aircraft leader, Wing Commander J. Baldwin, DSO, DFC, AFC, leading the sixteen rocket-armed Typhoon bombers, twice questioned his orders to attack, being sure the ships were British, the shore staff persisted with the strike in the belief that the minesweepers were enemy vessels trying to enter or leave Le Havre.

Signals made by Jason, recognition flares fired by all ships, the fact that the British ships did not fire back until they were already badly hit and sinking, and were being attacked a second time as they went down, all failed to deflect the Typhoons from their orders. Nor did the White Ensigns spread on the decks, the firing of the correct Very lights and signals by 10-inch searchlights deter them. They dived again and again, and within the space of a few short minutes, between 1330 and 1345 the flotilla was cut to ribbons. Two trawlers in company, Colsay and Lord Ashfield, were also attacked and suffered several casualties, but they and Jason managed to pick up the other ships’ survivors and wounded.

British destroyer HMS Tartar (F43) at a buoy.

Destroyer Action off Isle de Bas, 8-9 June 1944

The E-boat attacks, although not producing the results expected of them by the Germans against the mass of Allied shipping off the beaches, had resulted in a large expenditure of torpedoes. To get further supplies through quickly to the boats based at Cherbourg, it was decided that the destroyer flotilla at Brest should attempt to make the dangerous passage and at the same time to escape from what was obviously going to become a trap. If they made the journey successfully, these destroyers were to reinforce the German forces at Cherbourg for further attacks, and could also slip back to Germany if this became essential.

Accordingly, on the evening of 8 June, the four destroyers of the 8th Flotilla, under the command of Kapitän zur See von Bechtolsheim, sailed with a deck cargo of torpedoes, which added to his vulnerability. His force consisted of the big Z-32 and Z-24, armed with 5.9-inch guns, the ex-Dutch destroyer ZH-1, which was smaller and carried 4.7-inch guns, and one of the smaller so-called torpedo boats, T-24, with 4.l-inch guns. All had powerful torpedo armaments. Unfortunately for the Germans, they were quickly spotted and tracked as they made their hurried way northward. Aircraft made the initial sighting just before the cloak of darkness covered them, and plans were made to attack them.

The force sent to intercept them was the 10th Flotilla under Captain Basil Jones. This flotilla was split into the 19th Division, with the experienced Tartar as his leader and the Tribals Ashanti, Haida and Huron. This group was placed some two miles to the north of the 20th Division, which was placed to act as a guard, behind and beyond the leading ships of the line. This division consisted of the Polish Blyskawica and Piorun, and the British Eskimo and Javelin. The two British ships had somewhat less experience of this type of fighting. The whole force was disposed by the C-in-C, Plymouth, in the familiar Tunnel-type sweep, this time some twenty miles from the coast. The first ‘pass’ was made between the Isle de Bas and Isle Vierge but nothing was sighted and the expected collision course of 255 degrees drew a blank.

On the second westward run, at 0115 they had better luck, and Tartar’s radar picked up firm echoes indicating four large ships at a range of about ten miles almost directly ahead of the 10th Flotilla. Jones at once staggered his line to enable each of his destroyer’s radar sets to sweep ahead to its maximum efficiency, and to leave the Asdic operators with a clear sound field unmarred by the wakes of the next ship ahead. It was thus hoped that if the Germans adopted their usual course of firing torpedoes and running, advance warning would be available.

Captain Jones had studied earlier battle reports and made his plans accordingly. He expected the Germans to run true to form, and they did. In anticipation that they would turn and fire their full complement of torpedoes once the range had closed to less than 10,000 yards, he confidently held his course and bearing in staggered Line Ahead until 0122. Both British divisions were then altered by White Pendant 35 degrees to starboard and this was followed by a second turn of 50 degrees to port together, with the ships astern steering straight for their line of bearing positions. This had the effect of bringing the whole force’s powerful front gun armament to bear on the enemy line, and at the same time, it would comb the expected torpedo tracks. Sixty-four guns faced the oncoming German line, ready to fire.

As expected, at 0126 the Germans fired torpedoes, which were detected on their way. The range had come down to 5,000 yards and the thirty-two 4.7-inch guns opened fire in unison dead ahead and into the enemy line which was, by now, turning away in the time-honoured fashion. But this time, the British had the advantage of a steady course and full control. Although the massed German torpedo attack posed its usual deadly threat, and the Tartar leading the line was closely missed both to port and starboard, all torpedoes were avoided and the range was steadily reducing, making good hitting easier for the gunners. Receiving an unexpected battering, to which they could make no effective reply, the German force disintegrated as each ship sought its own salvation. Z-32 turned to port and steered northward; ZH-1 turned to port but went off at a tangent to her leader and finished up heading west, while the rearmost pair, Z-24 and T24, turned to port and steered a south-westerly course. The British flotilla was therefore forced to abandon its successful concentration and split up to follow the scattering German vessels as best they could.

Leaving the big Z-32 to be dealt with by the whole of the 20th Division, which was well placed to the north to deal with her, the Tartar and Ashanti concentrated on the second ship, ZH-1, while the two Canadian vessels went after the remaining pair which were heading south. Repeated hits so damaged the ZH-1 that her speed was much reduced. She vanished in a cloud of smoke and steam, and fire was switched to the T-24. This unfortunate was already fully engaged by Haida, who herself had been narrowly missed by enemy torpedoes.

Meanwhile the 20th Division had turned in Line Ahead 35 degrees to starboard and sighted their target, Z-32, on a parallel course. However, instead of turning towards her, as planned and practised, to concentrate their fire, the Polish ship held on. Z-32 immediately went into the normal routine, fired her torpedoes and turned away. The 20th Division came back with the same tactics as in earlier years, opening fire and turning away to fire a ‘fan’ of torpedoes from the tubes trained on the beam. The inevitable result was lost contact.

Her turn-away, moreover, resulted in undeserved good fortune for Z-32, who soon found herself undetected on Tartar’s beam and quickly opened fire. She heavily damaged the British leader before she herself was hit hard by the fire from both British ships. Captain Jones later described the damage:

Four shells burst about Tartar’s bridge, starting a fire abaft the bridge, cutting leads to her Directors, bringing down the trellis foremast and allradar, and cutting torpedo communications to aft.

The wheelhouse was also hit, killing the Assistant Coxswain; and on the bridge the PCO and torpedo control ratings were killed and a number wounded. As the mast fell over, the call-up buzzer from the aloft look-out position jammed on, and splinters pierced the upper deck of No. 1 Boiler Room causing loss of air pressure and reduction of speed.

The conditions of fire, noise, smoke and casualties were distracting, but with our immediate enemy silenced, I pressed on in Tartar, not realizing how much our speed had been reduced by damage to one of the boiler room ‘roofs’.

To the other ships of the flotilla, the damaged Tartar presented a sad sight. Tartar and Ashanti soon came upon the crippled ZH-1 stopped in the water and pointing to the north. Tartar passed close astern of her and raked her through in the time-honoured manner of Nelson’s day, at a range of 500 yards with guns in local control. Ashanti then fired two torpedoes into the stationary vessel and pumped in further 4.7-inch salvoes, which immediately resulted in a huge explosion and sank the ZH-1.

The Canadian ships quickly passed out of sight, intent on their victims, but although a fierce gun duel followed at high speeds the German ships again outpaced their Allied opponents, and the two Tribals were forced to give up the chase due to British minefields. Not before they had hit the Z24 with gunfire, however. Shells struck her charthouse, and her W/T office, and her after guns were put out of action, but she managed to get back to French waters. Her reprieve was but a temporary one, for there were no facilities to repair her damage, and in her stranded state she fell an easy victim to air attacks which delivered the final blows, as she lay in the Bordeaux estuary, soon after. The torpedo boat T-24 escaped undamaged. Z-32, after taking considerable punishment from Ashanti earlier, desperately struggled south trying to effect running repairs. She passed close to Tartar, which was in a similar state, and one wonders what the result would have been had the two cripples spotted each other at close range at this time. Z32 was not to enjoy immunity for long, however, as the two Canadian ships, returning from one chase, stumbled across her and once more the chase was on. Z-32 steered desperately to the east, but despite earlier damage and more hits from the Canadian ships’ forward guns, she seemed to be drawing away from them. She ran herself to the edge of the British minefield before turning south. The Canadian ships, joined by the Ashanti and Tartar at longer range, continued to engage her until, finally disorientated, the big destroyer ran firmly aground on the rocks of the Isle de Bas, heavily afire. She was later abandoned and blown up there. All the Allied ships returned to Plymouth Sound at 0530 to be cheered in by waiting crowds and welcomed by the C-in-C on the quay. On 10 June the Admiralty signalled to the Flotilla: The Board of Admiralty convey their congratulations to Officers and Ships’ Companies on the spirited action which has caused a potential menace to the main operations to be removed.

The Germans later praised the action as being a ‘significant success’ for their forces. Although only four of the Tribals had been effective in the battle against four German ships, they claimed to have sunk two of the six Allied destroyers and three light cruisers of the Glasgow type, which they maintained they had engaged!