The battle for Grozny was an intense six-week urban combat experience. Total Russian losses during the battle are estimated to be approximately 1,700 killed, hundreds captured, and probably several thousand wounded. Chechen casualties are completely unknown due to the inability to distinguish fighters from civilians and the decentralized and informal structure of the Chechen forces. Most of what is known of the battle is the result of researchers putting together snippets from contemporary news reports, official Russian reports, and interviews with participants on both sides. Both the Chechen and Russian leadership had, and continue to have, a vested political interest in portraying the performance of their forces in the best possible manner and denying operational difficulties. On the Chechen side the defense of the city has to be considered a victory despite the loss of the city. The outnumbered and underequipped defenders of the city prevented a larger, lavishly equipped force from securing the city for almost fifty days. Simultaneously, they inflicted significant tactical losses on the attackers, waged an effective information campaign, and greatly strengthened the political strength and legitimacy of the Chechen independence movement. The best that can be said for the performance of the Russian forces is that they eventually achieved their objective. The battle revealed a surprisingly low level of capability within the military forces of Russia.

The actual operational details of the battle are sparse, but a great deal is known about the tactical techniques applied by both sides. On the defense, the Chechens fought what some have called a defenseless defense. They relied on the unusual urban tactic of mobile combat groups rather than strongpoints. This tactic was particularly effective in the early stages of fighting because the Russians attacked to penetrate the city along specific axes of advance rather than on a broad front. The Russian approach, lack of adequate command and control, as well as insufficient numbers and disregard for their flanks, allowed the Chechen mobile groups to maneuver throughout the city at will and control the initiative in the battle even though they were on the defensive. As the Russian force grew in size and the Russian attack became more systematic in the second and third phases of the battle, it became more difficult for the Chechen forces to maneuver.

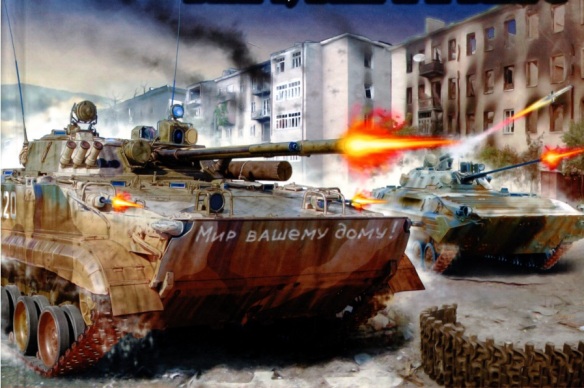

A Russian response to the Chechen tactic was the development of “baiting.” Small forces, such as a mechanized platoon or squad were sent forward to spring a Chechen ambush. Once exposed, a larger mobile force, supported by attack helicopters and artillery, used massed firepower to overwhelm the Chechen fighters. The Chechen response to the deliberate and expansive use of artillery and airpower by the Russians was “hugging.” Once engaged, Chechen fighters moved as close as possible to the attacking Russians to make it impossible for the Russians to employ their massive advantages in artillery and airpower. The Russian goal in the streets of Grozny was to identify the Chechen defenders before becoming decisively engaged and then destroy them with long-range direct and indirect firepower. The Chechen approach was just the opposite: stay as closely engaged with the Russians as possible. The employment of these tactics resulted in massive amounts of damage and significant civilian casualties as neither side considered collateral damage an important tactical consideration.

The most effective tactical weapons employed in Grozny were a mixture of old and new technology. The sniper armed with his scoped rifle proved a very reliable and essential element of successful urban combat. The Chechen forces employed formally trained snipers as well as competent designated marksmen in the sniper role. The Russian army, once they reverted to systematic offensive operations, included snipers to cover the infantry as they assaulted buildings. A new weapon, employed by both sides but with particular effect by the Chechen forces, was the rocket-propelled grenade, the RPG-7. This weapon was incredibly easy to use and lethal to all armored vehicles, including tanks. It was lightweight and easily carried by one man and so could quickly be positioned in the upper stories of buildings and on rooftops. The Chechens demonstrated the versatility of the weapon as they used it against armored vehicles, in open areas against infantry, against low-flying helicopters, and even in an indirect fire mode by launching the rockets over the tops of buildings at Russian forces on the other side. The Russians had access to this weapon as well but limited its use primarily to the traditional anti-armor role. Chechens sometimes increased the lethality of their snipers by equipping them with an RPG as well.

Russian forces employed a new weapon, one that had not been seen in urban combat before but which was ideally suited to the environment: the RPO-A Sheml. The Sheml was called a “flamethrower” by Russian sources but in its operation bore little resemblance to the traditional flamethrower that literally projected burning fuel at the target from short range. The Sheml was a rocket-propelled thermobaric weapon. It launched a 90mm rocket from a lightweight launch tube at targets up to a thousand meters away. When it hit the target the warhead of the rocket dispersed a fuel igniter which exploded after mixing with oxygen from the surrounding air. The resulting explosion was extremely powerful and hot. Enclosed areas such as bunkers, caves, and buildings magnified the effect of the explosion. Typically, any flammable materials in the vicinity were ignited. The Sheml became a favorite weapon for dealing with suspected sniper and RPG positions. The devastating effects of the weapon had a psychological impact on Chechen fighters, who rapidly abandoned firing positions before the Russians could launch a Sheml in response.

Tanks were a critical component of the Russian army’s success, as proven in other conventional urban combat experiences. However, the use of tanks evolved over the course of the month-long battle. At the beginning, Russian attacking forces relied extensively on tanks as the basis of operations: tanks led the attack and were supported by the other arms. Using these tactics Russian tank losses were extensive. The high losses among the tank forces caused the Russians to change their tactics by leading with dismounted motorized rifle troops and paratroopers. Dismounted forces were followed closely by infantry fighting vehicles and antiaircraft systems such as the ZSU 23-4. Tanks overwatched operations and added the weight of their main guns to the fight but were careful to always remain behind a screen of infantry.

From the very beginning of the battle, the Russians made frequent and liberal use of artillery. Artillery was a traditional weapon of the Russian army in battle but in Grozny it had only limited positive effects. The availability of supporting artillery in large numbers did much to reassure Russian troops of their firepower superiority over the Chechen forces. This was an important psychological effect given the shock to Russian morale caused by the New Year’s Eve attack. However, Russian artillery was not particularly effective against the Chechen forces because of the fluid nature of their defensive tactics. The lavish use of artillery, however, had a large adverse effect on the civilian population and on Russian civilian support for the war. Most of the residents of the central part of the city were ethnic Russians and they became the victims of Russian air and artillery bombardment. Estimates of civilian casualties in the six-week battle range from 27,000 to 35,000 killed. The number of wounded civilians was estimated to be close to 100,000. The Russian and international media reported negatively on the civilian loss of life and support for the Russian war effort suffered both within Russia and in the international community.