Thai success in the air contrasted with events on the ground, where neither side could gain an advantage. A French counterattack of January 16, 1941, on the Thai-held villages of Yang Dang Khum and Phum Preav in Cambodia ignited the war’s bloodiest battle. Victorious Thai forces were too weak to pursue the French, who withdrew in good order and effectively covered their retreat with accurately directed Foreign Legion artillery fire.

Admiral Jean Decoux, the Governor General of Indochina and Commander-in-Chief of Naval Forces, argued that Thailand’s power in the air and on land proved stronger than anticipated, but her forces were decidedly inferior at sea. He pointed out how the Royal Thai Navy comprised little more than two modern Japanese-built coastal defense vessels, each displacing 2,500 tons and armed with pairs of 8-inch guns. They were joined by 12 torpedo boats, 4 submarines, and a pair of old British-built, armored gunboats with 6-inch guns.

While these elements were outclassed and outnumbered by available French units, more vexing to Decoux were the 20 aircraft of the Royal Thai Navy, especially if they could be backed up in a timely fashion by far greater numbers dispatched from the Kong Thab Akat Thai. He nonetheless decided on an aggressive operation by placing the Groupe Occasionnel, a warship squadron, under the command of Capitaine de Vaisseau Regis Berenger, with orders to support a planned ground offensive against advancing Thai troops: “Attack the Siamese coastal cities from Rayong to the Cambodian frontier, compelling Siam government forces to retreat from the Cambodian

Berenger chose to attack the enemy anchorage at Koh Chang because its numerous, often lofty islets offered superb cover for an ambush. He needed to know the disposition of enemy surface forces before proceeding, so he ordered reconnaissance aircraft to be launched at first light on January 17. His two Gourdou-Leseurre GL-832 HYs were metal, low-wing monoplanes featuring twin floats and fabric-covered wings capable of being folded to permit stowage aboard ship. But the scouts with their unusual tailplanes attached to the underside of the rear fuselage, and two open cockpits in tandem for pilot and observer were inoperable due to a malfunctioning catapult.

Fortunately for the Groupe Occasionnel, it was covered by flyingboats based at Ream, and one of them reported the presence of a coastal defense ship accompanied by two torpedo boats on the early morning of January 14. Lieutenant Pleniemaison’s Loire 130 attacked with 330 pounds of bombs, while 7.5-mm rounds from its twin Darne machineguns raked the decks of HTMS Chonburi. But she out-maneuvered the onslaught, and drove off the seaplane with intense return fire.

Alerted to the presence of the enemy, Chonburi tried to break out of Ko Chang Harbor with another Thai torpedo boat, HTMS Songhkla, but they were surprised by Berenger’s flagship. Both vessels sank rapidly under a relentless barrage fired by the 9,350-ton light cruiser. The Lamotte-Piquet, then trained her eight 6.1-inch guns on a coastal defense ship, which had quickly gotten up steam and was trying to make good her escape on a northwest heading at 06:38. HTMS Thonburi traded shot for shot with the Lamotte-Piquet in a running battle amid the anchorage’s many islands. The former warship’s eight-inch shells could have wreaked havoc with her French opponent, but Thai gunnery was poor, and fires resulting from several hits broke out on the Thonburi by 07:15. Her speed fell off, enabling the sloops Dumont d’Urville, Amiral Charner, Tahure and Marne to catch up and join in the slaughter.

Against these overwhelming odds, she continued to fight on, even though suffering mounting damage. Desperate, repeated radio transmissions to the Royal Thai Air Force went unanswered, because its nearby base at Chanthaburi was closed until the beginning of the regular work day! Only an hour after the 7honburi began to burn did Kong 7hab Akat Thai commanders learn of the naval battle taking place just 12 miles away. In their panicky haste to make up for precious lost time, KTAT Corsairs mistakenly bombed vessels of their fellow countrymen, including the Dunburi, a coastal defense monitor, and, still worse, the Royal Thai Navy’s own flagship. The pilots’ inability to distinguish friend from foe was equaled by their attack skills, which, fortunately for all concerned, failed to inflict any casualties or damages. Twenty minutes later, a single Corsair appeared over Koh Chang to finally sortie against the real enemy. A bomb exploded within 15 feet of the Lamotte-Piquet, partially rupturing her port side hull, and damage control reported flooding.

Shortly thereafter, a combined flight of Martin B-10s and Mitsubishi Ki-21s went after the same warship. Impressive defensive fire from its four 75-mm antiaircraft guns spoiled the aim of the attackers, their bombs falling wide of the entire Groupe Occasionnel by 600 feet. By then, the badly damaged but resolute HTMS Thonburi got the range of the Lamotte-Piquet to make some hits on the light cruiser, until the burning Thai vessel’s decks ran with the blood of crew members killed in action, including her captain, Commander Luang Phrom Viraphan. His second in command redirected fire on the less-well-armored sloops, particularly the Admiral Charner, inflicting some damages and casualties before a salvo from the Lamotte-Picquet put the Thonburi’s after turret out of action.

No longer able to properly defend herself and beset with spreading fires, she made a dash for the imagined safety of shallow waters, where the French could not follow for fear of grounding their deep-keel warships. The Lamotte-Picquet fired a parting shot of 550-mm torpedoes after the fleeing vessel, one of which hit HTMS Thonburi, and she disappeared, presumed sunk, behind an island.

At 08:40, Corporal Chamraj Moungpaseart dove his Corsair on the enemy cruiser, hitting her squarely amid ships with a single, 110-pound bomb that failed to explode, though it did cause some damage. When Admiral Decoux read Capitaine Berenger’s report of Moungpaseart’s attack, he remarked that some Thai airmen obviously flew with the skill of veteran dive-bombers.’ A final, ineffective raid by KTAT Nagoyas at 09:40 closed the Battle of Koh Chang, which decimated Thai sea power with the loss of five warships and 36 men on the Thonburi, Songkhla, and Chonburi.

Eleven French sailors had been killed aboard the Lamotte-Picquet and her sloops. But all that remained of the Royal Thai Navy were four submarines and a few, small support vessels. No French ships had been sunk in the action, but every one incurred damages of varying degrees, particularly the Lamotte-Picquet, which required prolonged repairs. She would continue to serve as a light cruiser until disarmed during December 1941, in Saigon, where she was retired as a training ship. On January 12, 1945, carrier-based bombers from U.S. Task Force 38 sank the immobilized Lamotte-Picquet at her moorings.

Contrary to Berenger’s assumption, however, he did not sink the Thonburi. Although on fire and listing badly to starboard, she ran herself aground on a sand bar at the mouth of the Chantaboun River. After the French departed the combat zone, her surviving crew members were rescued by HTMS Chang, a transport that towed their gallant warship back to Koh Chang Harbor. She was later sent to Japan for repairs and used as a training vessel-as was her opponent-until her retirement after World War II. Today, her gun and deck belong to a memorial at the Royal Thai Naval Academy in Samut Prakan.

Undaunted by KTAT’s failure to turn the Battle of Koh Chang in their favor, its airmen continued to engage the enemy. In late January, the first of a dozen, two-place Mitsubishi Ki-30 light-bombers arrived from Japan. Powered by a 950-hp Nakajima Ha-5-kai, 14-cylinder, radial engine, the “Ann;’ as the Americans later called it, could carry 882 pounds of bombs over 1,066 miles at 236-mph cruising speed.

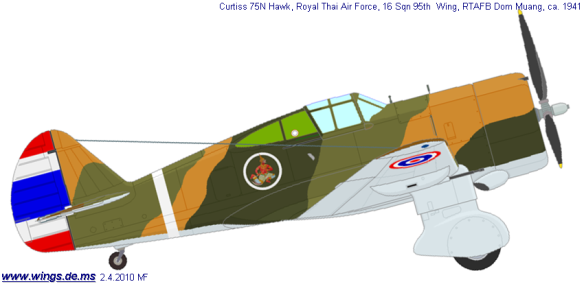

On the 24th, Flight Lieutenant Chalermkiat Wattanangura led a patrol of three Curtiss Hawks along the Thai border. At Ban Yang, near Aranyapradesh, they jumped a Potez 25 escorted by two Moranes. During the aerial combat that ensued, the French fighters were engaged, while Chalermkiat shot down the reconnaissance plane. Four days later, nine Mitsubishi Anns, four Curtiss Goshawks, and three Martin bombers, escorted by a trio of Curtiss Hawks, raided the Armie de /Air’s important airfield at Angkor, near Siem Reap. Several French fighters standing in the open were blown up or badly holed by shrapnel, and irreplaceable repair depots wrecked. Elated by his success, Wing Commander Fuen broke formation from the homeward-bound attackers, and flew back alone over Angkor to personally document the carnage at Angkor.

While photographing the smoldering enemy facility, he was himself jumped by a pair of Morane-Saulniers that had somehow managed to take off from the recently cratered airstrip. Fuen could not hope to fly a slow, ponderous bomber against two nimbler, faster interceptors, but he was left with no other option. Fighting for his life, he put the rugged Nagoya through maneuvers it had not been designed to withstand, while his rear gunner endeavored to keep both M.S.406s at bay by constantly firing in their general direction. This decidedly uneven aerial combat went round and round until both Moranes had exhausted all their ammunition. The French pilots flew alongside Fuen, and, to his amazement, waved goodbye before peeling away. After returning to the KTAT base at Chantaburi, he was further astounded to observe that his Mitsubishi had escaped the engagement without incurring a single bullet hole.

In fact, the Franco-Thai War, perhaps because of its brevity, was unmarred by atrocities on either side, but, on the contrary, generally conducted with chivalry and mutual, if grudging respect. The conflict’s last KTAT mission was conducted by Martin bombers of the 50th Bomber Squadron screened by 13 60th Fighter Squadron Curtiss Hawks and two Curtiss Goshawks on that same day, at 07:10 hours, against Pailin and Sisophon, which suffered extensive damage. These last, two Royal Thai Air Force missions went unopposed, because attrition had bitten deeply into the dwindling stocks of Armee de lAir fighters. By then, the war was stalemating. The Thais were marginally ascendant in the air, but they had been decisively defeated at sea, and both sides were deadlocked on land. Like Prime Minister Phibun, Japanese authorities wanted his armed forces to conclude their operations with the limited expulsion of colonial occupation troops in as short a time as possible, certainly inside a month.

After the French success at Koh Chang, however, the probability of a prolonged conflict, wherein Thailand’s ultimate victory was no longer certain, prompted Tokyo to impose an armistice on both warring powers. For its intended invasion of Burma and Malaya and the valuable raw materials-particularly oil-of these lands, Imperial Japan needed an active, cooperative alliance with either power, who were weakening each other in a mutually destructive conflict. The war came to a close when a January 28 cease-fire went into effect at 10:00 hours, followed May 9 with a Tokyo peace treaty signed by representatives of all three governments. In dictating its terms, the Japanese showed remarkable impartiality and fairness, making the French relinquish those original Thai enclaves of what had since become colonialized Cambodia and Laos but nothing more. While these territories comprised some 43,000 square miles, they nonetheless represented a fraction of French Indochina and had been, in any case, negotiated with Thai diplomats long prior to the outbreak of war.

The French, afraid all their colonial holdings would be carved up between Japan and Thailand, were relieved to learn so relatively little was demanded of them. Unlike the Treaty of Versailles, Tokyo’s accord did not demand reparations or stipulate a guilt clause, and neither side was declared “victor” nor “vanquished:” Its goal was the satisfaction of most, but not all territorial claims against the French, whose honor and colonial integrity were to be upheld, at least until early autumn, when gathering American intervention in China necessitated occupying the port of Haiphong by the Japanese.

Their formal request for “this temporary concession, to be returned to French authorities as soon as the military situation permits;’ was rebuffed by Governor General Decoux. Without further notice, Japanese forces took Haiphong against virtually no resistance. They were covered by some 500 warplanes, which prevented the badly outnumbered Armee de /Air crews from carrying out anything more than infrequent reconnaissance missions and furtive sorties against invading ground troops.

On September 25, the conflict’s one and only aerial combat took place when Nakajima Ki-27 fighters of the 84th Sentai claimed a Potez 25 observation aircraft. Before its Morane-Saulnier escort was also shot down, its pilot-the redoubtable Captain Tivoliere, who yet again managed to survive-scored a “kill” against his attackers. These were the only “official” losses in the air, although Sergeant Labussiere-the same Labussiere who had survived a crash landing following aerial combat with Thai fighters the previous January 11-jumped and destroyed a single Nakajima on patrol duty during the afternoon of October 20, after the agreed cessation of hostilities. Decoux concealed all knowledge of the attack. If word of the illegal “kill” had leaked to the outside world, international law would have obligated him to surrender the impetuous Labussiere to the Japanese for prosecution on homicide charges. Otherwise, the French would have to face a renewal of Japan’s overpowering aggression. As far as the Japanese knew, the lone Ki-27 simply went missing.

Throughout Thailand, the May peace agreement was celebrated with ecstatic acclaim as a unique, unmitigated triumph. Never before had a Southeast Asian people extracted concessions of any kind from European imperialists, an achievement unmatched in the whole modern history of the Orient since Japan defeated the Russian armada at Tsushima, back in 1905. But the billowing of national pride swelled into overconfidence among some Thai politicians and generals, who were certain their armed forces were now strong enough to deal equally with all outsiders.