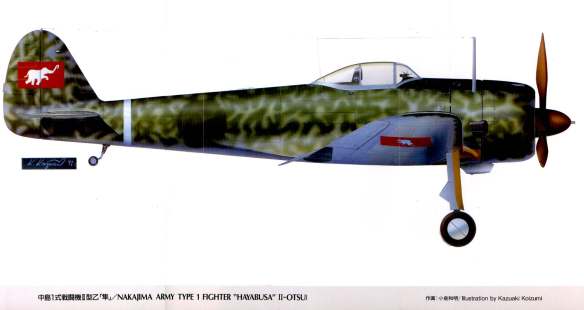

Ki-43-IIb Unit: BKh.13, Royal Thai Air Force RTHAFB Don Muang, circa 1944.

They were soon put to the test during the evening of December 7, 1941, when a request was received from Japan for free passage of its troops through Thai territory on their way to the invasion of Burma and Malaya. The sudden mobilization of British armies there necessitated rapid deployment, the Japanese explained, and Thailand was invited to take part in the operation for the reconquest of additional lost territories. If the Thais refrained from joining, permission was asked to cross their borders for “temporarily” engaging the enemy. The Japanese formally apologized for the urgency of the situation, which required an immediate response.

The note sparked intense debate among Thai government and military officials meeting in emergency session. Some urged defiance of the Japanese; others pointed out the suicidal futility of resistance. A few wanted to accept their offer of alliance. Still others hesitated to accept any proposal. While these contentious discussions raged back and forth, the impatient Japanese took matters into their own hands early the next day by simultaneously landing at four different places along Thai coastal provinces, including Samut Prakarn, south of the nation’s capital.

Individual army and air force commanders, minus any orders from their indecisive superiors in Bangkok, opposed the invaders at their own initiative with predictably disastrous results. The first three Curtiss Hawks that tried to take off from Weatatna Nakorn base at Aranya Prathet were quickly destroyed by 11 Nakajima fighters of the 77th Sentai sweeping in low over the airfield. Another pair of Hawks was similarly dispatched at Prachaub Kirikhan, where most of the 39 KTAT personnel lost during the brief campaign perished, and 120 survivors, grounded by the abrupt annihilation of their aircraft, were somewhat more successful as infantrymen, defending the base from numerically superior assaults. As soon as reports of the fighting arrived at Bangkok, Prime Minister Phibun contacted the Japanese over the strenuous minority objections of his government, and a cease-fire went into effect at 07:30, little more than three hours after the invasion began.

The Japanese proved themselves nonvindictive and ultimately generous conquerors. Thailand’s independence and the lands reclaimed during the recent war with the French were untouched, while troops and supply columns, seen nowhere else in the country, only occupied a territorial corridor enabling them to pass through a narrow strip of Thailand toward Burma. Instead of treating the Thais as defeated enemies, the Japanese once again solicited their alliance. On December 21, both peoples concluded a pact that guaranteed mutual assistance and close cooperation “in perpetuity.” Thereafter, KTAT received from Japan the first of what would eventually amount to perhaps 200 warplanes. Never before, or since, had the Royal Thai Air Force become so powerful.

But the price for such growth was Thailand’s participation in the invasion of Burma, plus a January 25,1942, declaration of war against the Anglo-Americans. Changing signs of the times were most apparent in the new insignia now carried by KTAT aircraft. Their blue-white-red roundels too closely resembled Allied markings, and were replaced by rectangles of the same colors. When these, too, resulted in occasional misidentification, they were substituted later that year by the image of a white elephant on a red triangle. This deltoid insignia appeared on either side of the fuselage, plus the upper and under-wing surfaces. Vertical stripes of the national tricolor adorned vertical stabilizers. Upper sides were dark green; undersides, light green, as worn by Imperial Japanese Army Air Force warplanes to further avoid confusion with the Allies, who, in fact, operated some of the same types flown by the Thais.

The arrival of Japanese aircraft in Thailand filled out the Kong Bin Yai Phasom Phak Payab, or “Northern Combined Air Wing;’ based at Lampang, where three squadrons-Foong Bin 21, 41, and 62-were already equipped, respectively, with Vought Corsairs, Curtiss Hawks, and newly arrived Nakajima Ki-27bs. Code named “Nate” by its U.S. opponents, Thai pilots knew the agile fighter as Ota after the Japanese city where the type was manufactured. Additional numbers replaced Curtiss Hawks of the Foong Bin 16 and were highly valued for their 3,010 footper-minute rate of climb afford by a 650-hp, air-cooled, radial engine. The b (Army Type 97b) was an improved version of the Ki-27, featuring a canopy affording better visibility and a more efficient oil cooler, together with provision for additional fuel tanks or four 55-pound bombs under the wings, which qualified the Ota for ground-attack duties.

To assist the Royal Air Force in flight instruction, the Imperial Japanese Army donated three gliders, all built by the Nihon Kogata Company: a Tobi primary kasa (literally, “umbrella”), one Ootori “soarer,” and a Hato elementary glider. In April 1941, the big Mitsubishi Ki-21s were at last available for service, enabling KTAT to establish its first bomber wing, Kong Bin Noi 6. They missed out on the Franco-Thai War, because crews were still in training, but now, throughout December, men and machines were winging their way over the Shan region of Burma in concert with old Martins, usually escorted by Nakajima fighters flying out of Lampang’s Koh Kha’s air force base in northern Thailand. During early 1942, Kong Bin Noi 6 extended its reach into China at the behest of its Japanese allies. Targets were confined to arms plants and marshalling yards in Yunna province, defended exclusively by antiaircraft batteries. They scored a few hits on the Thai bombers more by chance than design, but none were shot down.

In appreciation of these successes, the Japanese donated a dozen Martin B-10s recently captured from the Dutch East Indies Air Force. They and the Mitsubishis were temporarily diverted from bombing raids to humanitarian missions in October, when Kong Bin Noi 6 flew food supplies to the residents of Bangkok, then plagued by major flooding. On January 29, 1943, Kong Bin Noi 6 resumed its operations over China, striking the Mong Sae air base, which, reconnaissance revealed, had just received a batch of Allied fighters. These were destroyed with incendiaries, along with an arms depot that illuminated the city with its fiery annihilation. Several Thai aircraft were hit by flak, incurring only light damage. Crews of Kong Bin Noi 6 undertook almost 47 continuous months of missions against Burma and China for the loss of just one “Sally,” which accidentally crashed into a mountainside on September 6, 1942.

By late 1943, the squadron was relocated further south to Lom Sak air base, in Phetchaboon province, because the war that had already ravaged other Axis powers now threatened Thailand itself. As Allied longrange bombers were about to strike across Southeast Asia, Nakajima Ki-43-II-bs began to arrive from Japan for homeland defense. Known as the Hayabusa, or “Peregrine Falcon;’ it was responsible for the destruction of more Allied aircraft than any other Japanese fighter, including the more famous Zero. The fighter was light at just 5,710 pounds, maneuverable, and easy to fly, with a 1,150-hp Nakajima Ha-115 radial engine for a maximum speed of 329 mph at 13,125 feet. A pair of fixed forward-firing Ho-103 machine-guns mounted in the cowling fired 500 12.7-mm rounds.

Most of the 24 imported Hayabusas were formed into a special interception squadron, FoongBin 16, headquartered at Don Muang. Their first encounter with U.S. aircraft came on December 31,1943, as a flight of B-24 Liberators from the China-based 308th Bomber Group raided Chaing Mai and Lampang without causing any damage because both target areas were altogether missed. No less ineffectual were KTAT efforts to engage them. Thai pilots needed better instruction in the fine points of interception. They were on the receiving end of a March 2, 1944, raid carried out by Curtiss P-40s of the 14th Air Force. A pair of Warhawks strafed the airfield at Kengtung, but only destroyed a single Vought Corsair between them. Events in the South Pacific theater distracted the Americans for the next three months.

Their first attack on Bangkok occurred June 5, but KTAT fighter pilots, prepared this time for the reappearance of the old Liberators, were unable to catch up with the 55 B-29s, which were 28 mph faster. The XXth Bomber Command’s ineffectual raid on the Thai capital represented the operational debut of this new and monstrous warplane. When the same number of Superfortresses returned to destroy Bang Sue’s marshalling yards on November 2, they were intercepted this time by seven Ki.43s of Foong Bin 16 and twice as many Japanese Hayabusas. Flight Lieutenant Therdsak Worrasap scored accurate hits on one of the big bombers, which later crashed with the loss of all hands before reaching its base, but was himself shot down by the enemy’s defensive fire. He survived with severe burns, parachuting over Petchburi. Another B-29 was badly shot up by Pilot Officer Kamrop, who, like Worrasap, thereafter received his second Medal of Valor.

The KTAT and IJAAF pilots had pressed home 45 attacks against the combined firepower of 660 12.7-mm Browning Ms/AN machine-guns, losing two Thai and five Japanese fighters. Their interception spoiled the American bombardiers’ aim, and the marshalling yards suffered no hits.

On November 11, nine P-51 Mustangs and seven P-38 Lightnings sortied against a railway line between Chiang Mai and the Ban Dara bridge, damaging a locomotive, then turned their attention to Lampang airfield defended by just five serviceable Nakajima fighters. Out-numbered by more than three-to-one odds and almost totally outclassed by superior fighter planes, the Thai airmen fought like the peregrine falcons after which their aircraft had been named. A Lightning spun out of control under the guns of Pilot Officer Kamrob Plengkham, who then dove on a P-51 that disengaged from the battle after receiving several hits. Two more Mustangs were badly shot up by his comrades, and fled the scene of combat before one crashed in northern Thailand, the other inside China.

After making a forced landing, Flight Lieutenant Chalermkiats Ota sprinted from the wreckage of his Ki-43, as it was strafed by one of the Americans. They had nonetheless been prevented from destroying all but one of Lampang’s Hayabusas left parked in the open on the airfield. Although every KTAT pilot had been shot down and wounded, Chief Warrant Officer Nat Sunthorn was the only Thai fatality.

A week later, 10 B-24s raiding Bangkok were opposed by just three Hayabusas, which were mostly intimidated by the Liberators’ heavy defensive fire. Flight Sergeant 1st Class Wichien Buranalekha alone damaged a single B-24, which broke formation trailing smoke from its inner starboard engine, but successfully limped back to base.

Forty five more Superfortresses once more raided the Bang Sue marshalling yards on November 27. Although unopposed this time in the air, they yet again failed to hit their target and did not return until the following year, on January 3, 1945, to attack Bangkok’s Rama VI bridge. By then, attrition, unavailability of replacements, and lack of spare parts had so impacted the Royal Thai Air Force that it could only field five Nakajimas and three Curtiss Hawk biplanes, none of which was able to catch up with the much faster enemy bombers.

USAAF Mustangs reappeared on April 7, destroying seven fighters on the ground and killing as many personnel at the Don Muang airfield. Forty P-51s returned two days later, but were opposed by two Hayabusas. Both were promptly shot down, although their pilots survived to witness the further destruction of four more KTAT warplanes. The Royal Thai Air Force had been reduced to 14 Ki.43s, 4 of which were still operational, plus 8 Nakajimas, and 6 of these were not in service.

These few, surviving fighters were all that opposed a British Navy task force of nine destroyers, a cruiser, and the aircraft carrier, HMS Ameer, gathering to attack Chalong Bay, Phuket, between July 24 and 25, 1945. Commanders of the Royal Thai Naval Air Service had wisely withdrawn most of their own, remaining seaplanes before the operation commenced. Accordingly, supporting U.S. Navy F6F Hellcats found just one Watanabe to destroy; two more were damaged. A dozen of the reliable floatplanes were still in flying condition, and had performed their coastal patrol duties effectively, spotting enemy submarines and chasing off Allied reconnaissance aircraft. Imperial Japanese Navy commanders had been impressed with Thai diligence, and donated three specimens of their best seaplane in 1942 to the 1st Naval Squadron, which was upgraded to a Naval Wing with bases at Sattahip and Chalong Bay.

The “Jake;’ as Allied pilots referred to it, was a vast improvement on the old Watanabes, with its 1,080-hp Mitsubishi Kinsei 43 radial engine. It was fast for a seaplane at 234 mph, and could do more than merely reconnoiter with its 551 pounds of bombs. An extended endurance over 1,300 miles rendered it suitable for long patrols above coastal waters, where USAAF long-range heavy-bombers attempted mine laying operations in early 1944. Appreciative Japanese officials presented three more Aichi E13A-ls to the Naval Wing in May, after a B-24 was shot down into the Gulf of Thailand. This aerial victory bespoke Thai skill and determination, because the Jake had no forward armament, and carried only a single, rearward-firing, 7.7-mm Type 92 machine-gun for its observer.

The very notion of this lightly armed seaplane taking on a faster heavy-bomber bristling with 10 .50-caliber machine guns, let alone destroying it, was extraordinary. Apparently, the Aichi’s Thai pilot made straight for the intruder, setting a head-on collision course. Just before impact, he dove underneath the big bomber and along the underside, allowing his observer to fire upward into its belly. A fireball consumed the Liberator from which only its wings twirled into the Gulf.

World War II came to an end for Thailand on August 15, 1945, with the surrender of the last, remaining Japanese troops to the Allies. Just four years earlier, a Victory Monument had been erected to Thai servicemen who fell in the war against the French. It still stands in the capital’s Ratchathewi district, on a traffic island at the center of one of Bangkok’s busiest intersections.

An institution more specifically aimed at commemorating KTAT’s World War II veterans is the Royal Thai Air Force Museum, located on Phanonyothin Road, just south of Wing 6, at the Don Muang Airport’s domestic terminal. Established in 1952 for the preservation and restoration of historic aircraft used by the Kong Thab Akat Thai, its collection displays more than one ra’ra a’vis. Featured are the original Tobi and Hato gliders donated by Japan. Nearby stands KTAT’s leading fighter during the Franco-Thai War, a Curtiss Hawk 75N. Only two other examples exist-one at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, in Dayton, Ohio; the other at Duxford, in England’s Fighter Collection.

So, too, just three specimens still exist of the Curtiss BF2C Goshawk, one of which is housed at the Royal Thai Air Force Museum, together with an ancient Breguet 19. Found nowhere else is the Thais’ indigenous Baribatra Bomber Type 2, and the wreck of an Imperial Japanese Army Air Force Nakajima Ki-27b discovered by local fishermen near Nakhon Si Thammarat in January 1981.

Most rare is a Vought 02U Corsair, once the mainstay of nine air forces around the world, now the last one of its kind anywhere on Earth.