Italy’s foreign policy has generally had clear, but unassertive, objectives. Before unification, the lack of cohesion among ministates and principalities under Austrian, Spanish, or Pontifical jurisdiction made unrealizable any territorial ambitions on the part of those few states that were autonomous. Moreover, a paucity of industrial raw materials and the vulnerability of two long coastlines warranted a certain modesty. After the peninsula’s unification, however, the aim became to establish Italy’s credentials as a power by pursuing a colonial policy in Ethiopia and in Libya.

Successive governments also negotiated the so-called Triple Alliance, tying Italy to Germany and Austria-Hungary. However, Italy increasingly chafed at the limitations of the Triple Alliance. Calculating that Italy’s security required control over the mountain passes to its north and the absence of a rival power on the Adriatic, the Italian government competed for influence with Austria in the Balkans. It was calculated that Austria would see no reason to share either mountain passes or seas with the Italians in the case of a joint victory in a European war. On the other hand, a victorious Anglo-French alliance would surely have no objection to parceling out formerly Austrian holdings to an Italian ally.

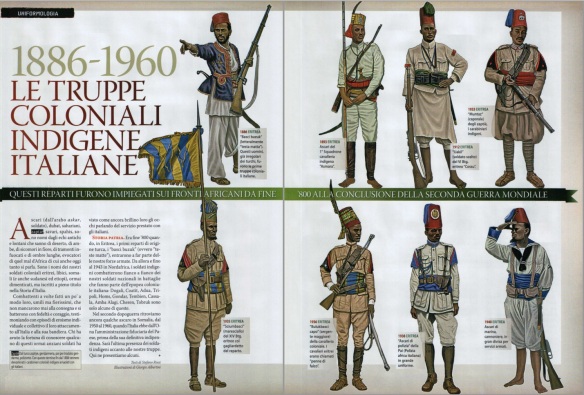

Readiness to experiment with the politics of violence was growing on the political right too. Italy’s colonial adventures, which began with Depretis in the mid-1880s, and continued under Crispi in the 1890s, failed to leave Italy with an adequate place in the sun and, on two occasions—at Dogali in 1887 and Adowa in 1896—ended in military setbacks at the hands of Ethiopian tribesmen. By the first decade of the 20th century, nationalist theorists (including some socialists) were claiming that Italy was a “proletarian” nation that had been robbed of its birthright by rapacious powers such as Britain and France. This resentful mood led directly to a short war with Turkey that ended with Italy occupying the Dodecanese Islands, including Rhodes, and most of modern-day Libya. These gains were confirmed by the Treaty of Lausanne in October 1912. Such a minor war (only 3,000 Italians were killed) was hardly sufficient for the more headstrong members of the nationalist intelligentsia, or for “futurist” thinkers such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, whose Futurist Manifesto (1909) described war as the world’s only “true hygiene.”

The desire for war at all costs was a decisive force in pushing Italy into war on the side of the Entente in May 1915, although a majority of the Italian people were opposed to intervention and Italy was bound by treaty to Austria and Germany. Italy had followed a pro-German foreign policy since 1882, when it joined the Triple Alliance. The Triple Alliance, which gave Italy an Austro-German military guarantee in the event of an aggressive French war, made perfect sense in strategic terms, but it was unpopular with a vocal section of Italian public opinion, the so-called irredentisti, who resented the fact that no effort was being made to recapture the “unredeemed” territories of Trento and Trieste. After the outbreak of war in August 1914, Italy’s leaders saw the opportunity to bargain for a return of the Italian-speaking parts of the Austrian Empire. Italy argued that it deserved compensation for entering the war, and a cynical auction took place between the two warring blocs of powers, with Austria eventually offering a generous territorial settlement in exchange for Italy’s at least remaining neutral. Giolitti famously wrote that the Central Powers had offered parecchio (a large amount) and favored neutrality. The Entente offered more, however. The Treaty of London, secretly signed in April 1915, promised to satisfy Italy’s imperial dreams in the eastern Mediterranean. Huge, intimidating public demonstrations were held by the nationalists during what was called the “radiant May,” and a climate of support for intervention was created. On 24 May 1915, Italian troops invaded Austrian-held territory near Trieste.

LIBYA

In the 16th century, the Ottoman Turks combined Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan to form Libya. Two hundred years later, a Libyan dynasty established independence from Turkey. Turkish control was reestablished in 1835.

By 1887, Italy had secured the acquiescence of Europe’s Great Powers for eventual Italian initiatives in Libya. Following France’s annexation of Morocco in 1911, the Italian government insisted on a counter for French gains. In October 1911, Italy landed troops and quickly proclaimed the annexation of Libya; Giovanni Giolitti proclaimed on the eve of the landing that the invasion was a “historical inevitability.” Within months, 150,000 Italian settlers had arrived in Libya. Libya was proclaimed to be under “the full and entire sovereignty of the kingdom of Italy” on 5 November 1911. Determined resistance, initially by Turkey’s Enver Bey, continued until 1931, however, when Italian forces under Rodolfo Graziani captured and executed the Senussi leader, ’Umar al-Mukhtar.

Italy carried the war against Turkey into the eastern Mediterranean. In April and May 1912 Italian warships entered the Dardanelles and shelled, then occupied, the island of Rhodes and some of the Dodecanese Islands. By the fall, several Balkan states had declared war on Turkey, leading it to sign the Treaty of Lausanne with Italy on 18 October 1912. Under its terms, Italy was to end its occupation of the islands (which it failed to do) in exchange for the Turks leaving Tripoli (although they were to retain religious primacy by appointing a caliph).

Libya’s role in World War II was as a springboard for Italian moves against Egypt—and subsequently, as a theater of Italian military debacles. Italy’s armed forces suffered a series of disastrous defeats in Libya, and the territories were liberated by the British. Libya was recognized as an independent state after Italy signed the peace treaty with the Allies in February 1947. Subsequently, the United Nations established Libyan independence from Italy (1951) under a Senussi monarch, Idris I. By 1969, oil revenues had inspired a group of ambitious army officers, led by Mu’ammar Gadafi, to overthrow the monarchy in favor of “modernization.” One of Gadafi’s first acts, between January and July 1970, was to seize all property belonging to Jews and to 35,000 Italians. While the Jewish community was compensated with 15-year bonds, the Italian community was denied any compensation as reparations for the depredations Libya had suffered during Italian rule. Relations between the two countries became extremely strained, although in February 1974 Italy and Libya signed an accord in Rome that committed Libya to send to Italy 30 million tons of oil (up from 23 million) in exchange for technical assistance in building petrochemical facilities and shipyards, and improving agriculture.

ETHIOPIA

Some 20 years after unification in 1861, Italian governments embarked on a program of imperial expansion. After France had blocked Italian ambitions in Tunisia, Italy made inroads on the Red Sea, occupying several cities in what was to become Eritrea. Between 1887 and 1889, the Italian government aimed at establishing a protectorate over neighboring Ethiopia, to which Britain agreed so long as Italy remained no less than 100 miles from the Nile and did not interfere with the flow of its water. When Menelik, Ethiopian King of Kings, gave France a railway concession in exchange for munitions and other supplies and renounced the 1889 Treaty of Uccialli (which, in the Italian reading, had given Italy a protectorate over Ethiopia), Italy declared war. Menelik’s 100,000-strong force roundly defeated the badly led 25,000 advancing Italians at Adowa on 1 March 1896. The immediate consequence in Italy was a wave of popular strikes and protests that forced the government of Francesco Crispi to withdraw the army and to resign. In November 1896, Crispi’s successor, Antonio Di Rudinì, signed a peace that left Italy with Eritrea but recognized the independence of Ethiopia.

Benito Mussolini took Italy’s revenge nearly four decades later. After creating border incidents in the unmarked area between Italian Somaliland and Ethiopia, the Duce provoked a brief but bloody war of conquest, opening hostilities on 3 October 1935. Foreign military observers were impressed by the speed of Italy’s victory over a territory larger than metropolitan France, its ruthless use of aircraft against civilians, and its use of gas against the poorly equipped Ethiopian army. In May 1936, Addis Ababa fell, and Emperor Haile Selassie fled the country, not to return until British forces recaptured Ethiopia in the course of World War II.

Mussolini’s victory was also a diplomatic triumph. Playing on the imperial powers’ fear of Germany, Mussolini was able to extract from the French a virtual blank check to do as he wished so long as no French colonies were threatened and from the British a policy in the League of Nations of avoiding sanctions that might antagonize the Italian government. The League’s threats regarding oil shipments and scrap iron sales did nothing to impede Italian acquisition of those war goods in trade with non-League members, including—conspicuously—the United States. Moreover, League threats enabled Mussolini to portray Italy to the Italian public as the struggling “proletarian” nation facing alone the hostility of the plutocratic European powers.

The conquest of Ethiopia, added to Eritrea (after the war, incorporated in newly independent Ethiopia) and Somaliland, created Italian East Africa, thereby enabling Mussolini to confer on King Victor Emmanuel the title of emperor and to make Pietro Badoglio viceroy. For many, the conquest was proof of Mussolini’s boast that Fascism would show the world that Italy could be a nation of warriors. Subsequent failures in Greece and North Africa in 1940–1941 would prove that such hopes had no military basis.