Chariots

Apart from weapons and panoply, both the Greek and Trojan chiefs were sufficiently wealthy to maintain horses and chariots. These were essential to their way of fighting. The normal purpose of a chariot was to carry a fully armed warrior to the battlefield, where he would dismount and fight on foot, while his charioteer waited at a discreet distance with the horses and vehicle. If the warrior survived, he would eventually retire from the fight, remount his chariot and be driven back to his own lines.

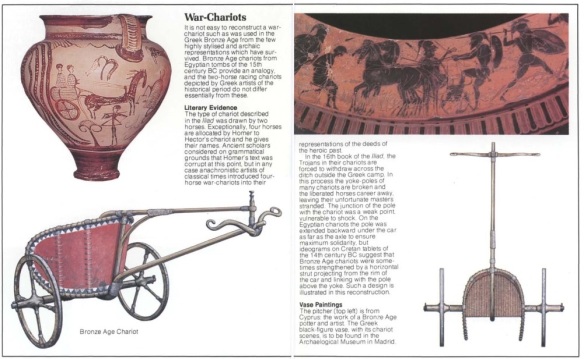

In practice, chariots often became more deeply involved in the fighting. They were frequently within bowshot, spear throw – or even stone’s throw – of the enemy. Homer describes how an arrow missed Hector in his chariot and killed his charioteer. Another charioteer was later killed by a stone flung by Patroclus. In the thick of battle, horses and chariots ploughed their way through the wreckage of enemy chariots, trampling and crushing the bodies of fallen men, while they themselves were spattered with blood. Patroclus, with a thrust of his spear, impaled an enemy warrior in his chariot and hauled him out, over the rim of the chariot, still impaled, like an angler hauling a fish to land. The chariot needed smooth terrain for efficient performance; on difficult ground the pole that connected the yoke with the car itself could easily break, allowing the horses to bolt. This happened to many Trojan chariots as their drivers tried in vain to negotiate the ditch round the Greek camp.

Homeric chariots were drawn by two horses and carried two persons, the warrior and the charioteer. A detailed description of the chariot of the goddess Hera is instructive, though a chariot owned by a goddess must be presumed more luxurious than those available to mortal men. Hera’s chariot had an iron axle-tree. Her horses had gold frontlets. The circumference of the wheels was of gold, with bronze tyres, and the centre was of silver. The wheels themselves had eight spokes, though in early artistic representatives of chariots four spokes are characteristic. In contrast, the axle-tree of Diomedes’ chariot was of oak, not metal.

The highly ornamental turn-out of Hera’s chariot is possibly fanciful, just as the shield of Achilles, fashioned by Hephaestus, the smith of the gods, can be in no way regarded as typical. Yet we may have here the faithful description of a ceremonial chariot, resembling in some respects those of Tutankhamun’s tomb with their rich gold and inlay. These, too, were products of a world in which iron artefacts were making a first appearance.

Methods of Fighting

In normal circumstances, as we have observed, the Homeric warrior chieftain dismounted from his chariot and approached the enemy on foot. He carried either one or two spears, which he launched against his opponent. If the enemy remained unscathed, he then protected himself with his shield against the inevitable retaliatory shafts. If the spears of both parties were thrown in vain, the two champions might immediately set about each other with swords or, before resorting to these weapons, they might hurl heavy stones or small rocks at each other. With these ready-to-hand missiles the Trojan plain seems to have been extremely well provided.

There was a good deal of opportunitism in such fights. When Menelaus and Paris tried to decide the issue of the war in single combat, Menelaus’ sword broke in three or four pieces against the crest of Paris’ helmet. Menelaus, however, despite his disappointment, seized Paris by the helmet crest and began to drag him towards the Greek lines. Paris was thus nearly strangled by his helmet strap, and no doubt would have been but for the attention of his goddess mother, who arranged for the strap to break. Menelaus was left holding the helmet while Paris made good his escape.

Most descriptions of fighting centre in the heavily armed leaders themselves, but attention is drawn to the large numbers of the Greek army and the Trojans are sustained by one contingent after another of loyal allies. In scenes of violent fighting, not only are we made aware of anonymous casualties but of many flying spears and arrows sped by anonymous hands. The rank and file of the army is described as fighting in formations (phalanges). Both sides were marshalled by their leaders in good order, but after battle was joined the scene was confused and sanguinary. The enemy ranks were more easily broken when one of their leaders was killed. This might lead to full-scale rout, when chariots were useful in pursuit. It does not, however, seem that the word phalanges – Homer only once uses the singular phalanx – denoted the closely packed formations with which it was associated in the fighting of a later epoch. Quite certainly the Homeric phalanx did not rely on the spear as a thrusting weapon as the classical phalanx did.

Discipline in the Greek army was on the whole good. The Greeks marched in silence, unlike the Trojans who chattered volubly, perhaps because of their language and liaison difficulty. One notably insubordinate character on the Greek side should, however, be mentioned in this context. Homer is very contemptuous of Thersites, who was a thorn in the flesh of the Greek leadership. His demagogy was not of the subtle kind which we have noticed in Agamemnon and Achilles, but consisted in raising laughs at the expense of the commanders: something which, in the circumstances, cannot have been difficult. Odysseus at last beat him and reduced him to tears. In the Aethiopis, Achilles grows sentimental over the Amazon queen whom he has killed in battle. Thersites accuses him of having been in love with her. But Achilles is unamused, and kills Thersites.

In the Iliad, there are frequent allusions to arrows, though as a weapon the bow seems to have been secondary to the spear. Some of the leaders on both sides were good archers, notably Paris and Pandarus among the Trojans. Of the Greeks, Teucer was the best archer, shooting down nine of the enemy in the course of the Iliad. But like other aristocratic archers, he was also able to fight hand-to-hand with spear and shield; when his bow string broke he was quick to arm himself with other weapons. Odysseus, according to the Odyssey, was conspicuous for his archery, but he did not use a bow in the Trojan War except on a very special commando mission, which we shall describe shortly. Odysseus, in fact, left his bow at home when he came to Troy.

Generally speaking, in Homer, “a good spearman” is synonymous with “a good fighter”. Yet archery was a crucial factor in the Trojan War. Both Achilles and Paris met their deaths from enemy arrows. It had been prophesied that Troy could not be taken without the bow of Philoctetes, the unfortunate Greek leader who languished long in the island of Lemnos, hors de combat and suffering from a festering snake-bite. Only when his services were re-enlisted was Paris killed and Troy taken.

Not only Philoctetes himself but his whole contingent were noted for proficiency in archery, while on the Trojan side the Paeonians, who came from Macedonia, constituted a corps of archers. Apart from this, the presence of massed bowmen may be inferred from the frequent reference to arrows, not all of which were launched by the bows of the aristocracy. It should perhaps be noted that the bows described by Homer were not of the most efficient kind. Nor were they used in the most efficient way. The bows themselves were composite, made of two curved horns joined at the centre. The string was drawn by the archer only to the breast, not to the ear as was done with the English longbow of the Middle Ages. The range of an arrow was possibly not much greater than that of a well-thrown spear.

Greek Strategy and Siege Warfare

The prose summary of the Cyclic epic narrative tells us that, after the death of the Trojans’ ally Eurypolus, the Greeks “besieged Troy”. Whatever this implies, it is not recorded that during the first nine years of the war any attempt was made to starve Troy into surrender. Indeed, the arrival of successive relief forces proves that any such attempt would have had little prospect of success. There were no walls or trenches of circumvallation. On the contrary, the Greeks were obliged to dig a ditch and build a rampart on the shore to protect their own camp and beached ships. After the withdrawal of Achilles and his troops from the war, Hector led a heavy attack on the Greek camp and penetrated the ramparts in an almost successful attempt to burn the ships. The situation was at last saved by Patroclus, commanding Achilles’ troops and wearing Achilles’ armour.

After Achilles’ own return to the war, the Greeks were able once more to take the offensive. According to one tradition an argument took place between Achilles and Odysseus as to whether Troy could best be captured by force or fraud, each of the two heroes making recommendations in accordance with his own character and abilities. Achilles, in pursuit of his policy, led a violent attack on the Scaean gate (i.e. the West gate) of the city and died fighting there. Odysseus’ counsels were vindicated when Troy was eventually captured through the stratagem of the Wooden Horse.

Not only was no attempt made to starve Troy into surrender, but no assault was made upon the walls. It should be stressed that Achilles’ final attack was launched against one of the city’s gates; and this in turn should remind us that the Trojans, in making their earlier attack on the Greek camp, broke in through the camp gates. Hector himself smashed the gates in with a heavy stone, breaking the hinges and the long bar which held them. At the same time, he had ordered that chariots should be left temporarily at the edge of the ditch and assault made against the rampart on foot. One commander disregarded his orders and attempted to pursue the flying enemy through an open gate on the left flank of the beached ships. But the gate was well defended and the assault came to no good. Meanwhile, the outcome of the fight on the ramparts remained in doubt, though the Lycian leader Sarpedon succeeded in dismantling some of the battlements. When the attackers were eventually driven out of the camp, they poured back over the ditch, many of their chariots – which had previously entered the enclosure – coming to grief in the process.

The inference to be drawn from these facts is that the Greeks of the Homeric period knew virtually nothing of siegecraft. By contrast, the eastern peoples of whom we hear in the Old Testament were capable of both reducing cities by starvation and of attacking fortifications. It might be possible to draw the further inference that the Trojans were more skilful than the Greeks in assailing fortified positions – something which they had perhaps learnt from their Oriental contacts – though it seems unfair to compare the ramparts of a military camp with the permanent walls of a city.

Intelligence and Commando Operations

The Thracian expedition in defence of Troy, to which we have just referred, was singularly ill-fated. Its leader, King Rhesus, did not survive his first night on the Trojan plain. The story is told in the Tenth Book of the Iliad. On the night in question, the Trojans were deployed on the plain before their city, poised to strike at the Greek camp. They were now under no pressure to retreat within their walls and their watch fires were everywhere visible. The Greeks were tense and anxious. If possible, some communicative prisoner was required, from whom the enemy’s immediate intentions might be learned. In order to gain such intelligence, Odysseus and Diomedes volunteered for a highly perilous night reconnaissance.

By good luck, Hector had also sent out a Trojan spy called Dolon, to bring back information about the state of affairs in the Greek camp. Odysseus and Diomedes encountered Dolon in the darkness. After a brief chase, they captured him, induced him to talk and then killed him. Apart from other useful information, they learnt the position of Rhesus and the newly arrived Thracian allies. These became their target. The Trojans, according to Dolon’s information, were keeping watch while their allies slept. His information proved correct. Odysseus and Diomedes slaughtered 12 of the Thracians who surrounded Rhesus and finally killed the king himself, driving away his fine Thracian horses. On the way back to the camp, they stopped to collect the bloodstained arms and equipment of Dolon, which they had hung on a clump of tamarisk to mark their route.

The differences of arms and equipment described in Book Ten from those which feature elsewhere in the Iliad have led some scholars to regard the episode of Dolon and Rhesus as an interpolation. For the purposes of the night raid, Diomedes wore a leather helmet without a crest, while Odysseus borrowed a bow and quiver of arrows, setting on his head a leather-and-felt cap overlaid with boar’s tusks. It must be remembered, however, that the occasion was exceptional. For a night operation of this kind, it was only natural to avoid the use of brazen armour which would gleam in the light of the Trojan watch fires.

Information about chariots and their use may also be gleaned from the episode. Not only Rhesus, but also all his henchmen possessed chariots. Diomedes at one point considered dragging Rhesus’ chariot by hand or even lifting it in his arms with the valuable armour inside it. This, even when one allows for Diomedes’ heroic strength, suggests that the Thracian chariots were very lightly constructed. Dolon’s information related not only to the Thracians but to other allies of Troy, and he described the Phrygians and Maeonians in words which can most naturally be interpreted as meaning that they were chariot-fighters and chariot-owners. Among the Trojan allies, chariots were perhaps not always a purely aristocratic prerogative. One gains the impression that in some contingents a chariot and two horses amounted to standard equipment. There is no hint of this in the account of the Trojan allied forces given at the end of Book Two, but such an interpretation accords well with the prominent part later played by chariots in the attack on the Greek camp.