On December 30, 1941, HMS Triumph dropped off Lt George Atkinson, a soldier working for the Special Operations Executive, who was to meet up with 18 Allied soldiers who had escaped from Italians and bring them back to the submarine.

But HMS Triumph failed to show up again and the group’s cover was blown. The men were all arrested, including Lt Atkinson who was later charged with espionage and shot.

Submarines figured prominently in both world wars but in each case attention has focussed mainly on the role of the German U-boats, ignoring the work of British submariners and for that matter their American counterparts who did so much to interrupt supplies from Japan’s newfound empire to the home islands. British submariners wreaked havoc in the Baltic and the Bosphorus in the First World War, and maintained an outstanding campaign in the Mediterranean in the Second World War. So much of this has passed by unremarked and with little attention.

As in the Fleet Air Arm, the Royal Navy’s submariners received extra money, but while the former described it rather nobly as ‘flying pay’, the submariners were blunt and to the point; to them it was ‘danger money’. Both these sections of the Royal Navy had been regarded as not very respectable when first formed, and indeed one First World War submariner was turned down for an important posting despite being favoured by an Allied government because the Admiralty thought he was ‘something of a pirate’.

Submariners and airmen were a breed apart. They had come together briefly between the two world wars with the ill-fated M2, the Royal Navy’s only attempt at an aircraft-carrying submarine whose aircrew, flying the diminutive Parnall Peto seaplane, were reputed to have received both danger money and flying pay. The extra money was necessary to attract men into the submarine service, for apart from the extra dangers there were many other hardships including cramped accommodation with the smell of diesel oil always present and a shortage of fresh water, which was why beards, known as a ‘full set’ in the Royal Navy, were so common among submariners. The Submarine Service was organized in flotillas for control and administrative convenience. There was never a set size for a flotilla; it could be just two or many more vessels, but they were usually grouped around a base such as the headquarters, HMS Dolphin, a stone frigate at Haslar, Gosport, or a depot ship such as HMS Forth.

Submarines were more than just another means of striking at enemy shipping. In contrast to the nuclear-powered submarine that spends most of its operational life submerged, Second World War submarines spent much of their time on the surface, only diving when threatened or when needing to be concealed before making an attack. Many attacks were made on the surface, using the deck gun rather than a more expensive torpedo, of which only replenishment stocks could be carried. The submarines of the day could cruise at a reasonable speed on the surface, but were very slow when submerged unless they made a high-speed dash, itself still not very fast, in which case their batteries would need recharging after about an hour.

Submarines could be used for mine-laying, inserting special forces and for reconnaissance or guiding an attacking force towards a landing area and also to carry urgent supplies. They had a greater radius of action than a destroyer and made use of much less manpower. In theory, they could get much closer to an enemy warship than a destroyer without being detected. The Royal Navy’s submarines varied greatly, ranging from the larger boats (submarines were never ships) for mine-laying and smaller craft for operations in confined or shallow waters, and of course there were the X-craft, the midget submarines.

Among the more notable successes of British submarines were the torpedoing and sinking of the German light cruiser Karlsruhe off Kristiansand during the Norwegian campaign by Truant on 9 April 1940. Later the ‘pocket battleship’ or Panzerschiff Lutzow was caught by Spearfish, commanded by Lieutenant Commander John Forbes, as the German ship was on her way from Norway to Germany for repairs to bomb damage. Although not sunk, Lutzow was disabled and had to be towed into harbour at Kiel.

This was not the last British success against a major German warship. The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, believed by many to have fired the fatal shell that destroyed HMS Hood and which had participated in the celebrated Channel Dash in February 1942, was discovered in Norwegian waters by Lieutenant Commander George Gregory in Trident on 23 February 1942 and a well-placed torpedo blew off part of her stern. A slow crawl with a temporary rudder to Trondheim was needed for temporary repairs before the ship could go to Kiel for permanent repairs, putting her out of service for the rest of the year.

British Submarine Strategy

Submarine strategy and tactics varied greatly between the belligerent nations during the Second World War. In 1939, the British Admiralty decided that the priority target for British submarines would be enemy warships. Submarines were to wait in their individual patrol areas, submerged, waiting for enemy warships to appear. By 1941 this strategy had been amended, especially in the Mediterranean where submarine commanders were given what amounted to a roving commission to attack anything that appeared worthwhile and, of course, merchantmen supplying Axis forces in North Africa or the Balkans were very worthwhile. The same approach later applied in the Far East.

The Royal Navy did not neglect specialized craft, including the midget submarine. After experimenting with a one-man design known as the Welman – basically a cross between a midget submarine and a human torpedo – British midget submarines evolved into the X-craft with a four-man crew. One or two members of the crew had to leave the craft in wet suits with breathing apparatus to place explosive charges on the target. This was a different approach from the Axis navies, who used midget submarines armed with torpedoes carried externally. The finest hour for the X-craft was on 20 September 1943 when six of these vessels penetrated the defences around the Altenfjord in Norway and placed explosive charges on the hull of the German battleship Tirpitz, damaging her machinery and main armament so that she was out of action for seven months. Tirpitz had earlier been the target for British human torpedoes, known to the Royal Navy as ‘chariots’, that had mounted an unsuccessful attempt to sink the ship in October 1942.

Later, on 6 June 1944, two X-craft undertook beach reconnaissance before the Normandy landings and then provided guidance to the British beaches.

Other targets included a floating dock in Norway, while a development of the X-craft, the XE-craft, was used in the Far East to disable Japanese communication cables and they also damaged a cruiser.

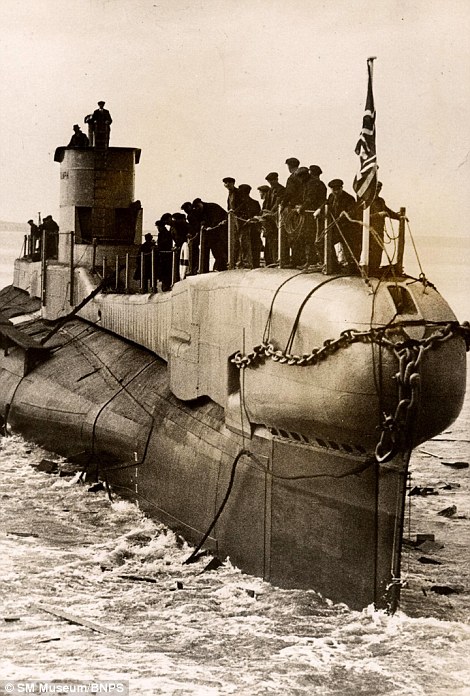

During the Second World War, British submarines sank 169 warships, including 35 U-boats, and 493 merchant vessels, but at a high cost with no fewer than 74 British submarines sunk, a third of the total number deployed during the war. A third of British submarine losses were due to enemy minefields. Just one submarine, Triumph, survived contact with an enemy mine and her survival was all the more remarkable as she lost her bows as far back as frame eight, which meant that she also lost her torpedo tubes and ten torpedoes!