For both commanders, the crisis of the battle had now been reached. It was unusual for the French to display such iron tenacity in a prolonged firefight, and they were doing so now because they believed they were winning. They had seen off Colborne’s brigade and the Spaniards and now Houghton’s battalions had shrunk to small scarlet oblongs standing isolated among their dead and wounded. In Soult’s eyes their protracted stand, which had cost his men so dear, entirely contradicted every tenet of military logic; even so, however gallantly they had behaved, their end could not be delayed for many more minutes. It was at that moment that Abercrombie’s brigade, full of fight, had appeared to ravage the right flank of his assault column and flung it back in disorder. His sole remaining reserve was Werlé’s brigade and he could only hope that it retained sufficient élan to restore some momentum to the attack and enable his troops to administer the coup de grâce as quickly as possible.

For his part, Beresford had reached the lowest point in his professional career. The Spaniards had received a mauling and could no longer be relied upon to do any serious fighting; and in Stewart’s 2nd Division, which had already fought itself to within an inch of destruction, the ammunition supply had begun to fail. Beresford undoubtedly considered himself to be beaten, and, deeply depressed, his only consideration at that moment was to save as much as he could of his army. Orders were given for Alten’s Germans to abandon Albuera village and for Hamilton’s Portuguese division to reposition itself so as to cover the line of retreat. These orders were being put into effect when the course of the battle took a sudden and totally unexpected turn.

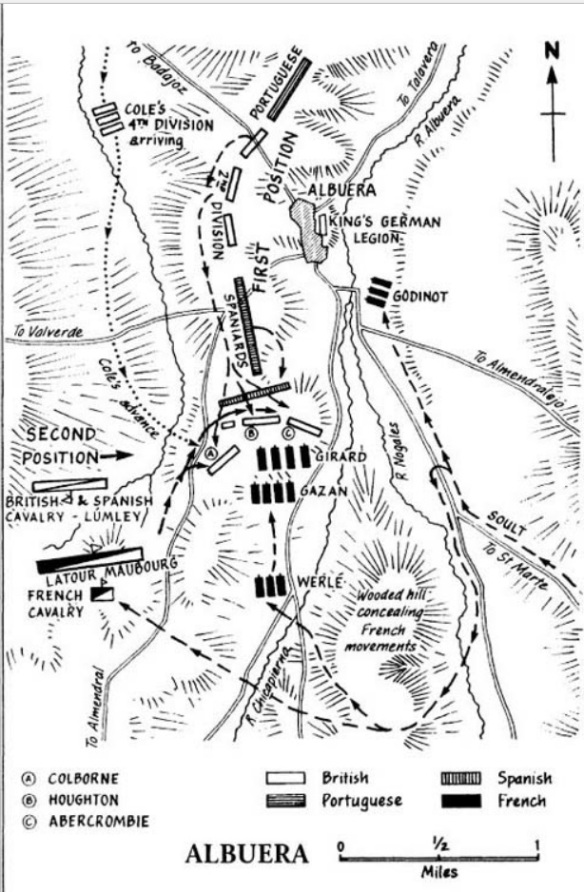

One of Beresford’s staff, 26-year-old Colonel Henry Hardinge, did not agree with the Army Commander’s gloomy assessment of the situation. Acting entirely on his own initiative he galloped across to confer with Sir Lowry Cole, whose 4th Division was positioned in reserve behind Lumley’s cavalry, urging him to mount an immediate counter-attack on left flank of the French and so stabilise the situation. Cole’s division consisted of two brigades only, Lieutenant-Colonel Sir William Myers’ Fusilier Brigade (1/ and 2/7th (later Royal) Fusiliers and l/23rd (later Royal Welch) Fusiliers, and a Portuguese brigade under Brigadier-General Harvey, and while he fully appreciated the point of Hardinge’s argument he was reluctant to commit his troops without a direct order from Beresford. Myers joined the discussion, pointing out that the French were on the point of launching their final assault and emphasising the urgency of the situation. Cole gave way but, unlike Stewart, he insisted that adequate precautions should be taken to protect the flank of the counter-attack against cavalry.

The divisional deployment was completed quickly and efficiently. All ten of the light companies, British and Portuguese, were formed in column on the right flank. Then, in line but echeloned back somewhat to the left came the four battalions of Harvey’s brigade, consisting of the Portuguese 11th and 23rd Regiments. Myers’ brigade came next with, from right to left, the l/7th, 2/7th and l/23rd, their left flank being protected by a column formed by a Portuguese light infantry unit of the Loyal Lusitanian Legion. The two brigades were drawn up in battalion columns at quarter distance so that, when the moment came, they could deploy quickly into line.

Those waiting to advance could see that the situation on The Ridge was deteriorating minute by minute. As already mentioned, Abercrombie’s brigade had pulled back into dead ground when its ammunition began to fail. Now, the battered remnants of Houghton’s brigade were being pushed steadily back by Werlé’s triumphant battalions, who already held the summit. To their right, the Polish lancers could be seen hovering in the area of the captured German battery. At length, satisfied that he had done all he could, Cole gave the order to advance. Never was a counter-attack more desperately needed, and never was one more exquisitely timed.

As the battalion columns passed through the intervals between Lumley’s squadrons, Latour-Maubourg could hardly believe his eyes. For the second time within hours Allied infantry were advancing unsupported within striking distance of his horsemen. Leaving the major portion of his strength to hold Lumley in check, he launched four regiments at Harvey’s brigade. On this occasion, while the attack would be delivered frontally against troops in column rather than, as in the case of Colborne’s brigade, against the flank and rear of battalions in extended line, a similar outcome was clearly anticipated. For a moment Cole, knowing that the Portuguese had never been in action before, held his breath. He need not have worried, for Harvey’s regiments had been trained to British standards, in which a well-drilled platoon in two ranks could fire up to five volleys a minute. The Portuguese, moreover, were perfectly steady, firing volley after volley that felled horses and riders until the French, having had enough, galloped back whence they had come. Harvey then formed a protective shoulder with which to cover the further advance of Myers’ brigade.

The Fusiliers, in their tall, peaked, bearskin caps, were the finest-looking British troops in the field that day, despite their worn uniforms and a recent issue of locally made buff-leather boots that hurt abominably. They tramped steadily upwards, breaking up a firefight that had developed in the smoke and confusion between a Spanish unit and some British troops, the latter possibly survivors of Colborne’s brigade. Ahead lay the massed ranks of the French, now in possession of the summit and believing themselves to be on the brink of victory.

Lieutenant John Harrison, commanding one of the 23rd’s companies, recalled that only when the brigade was within musket range, i.e. less than 200 yards, and the French had actually opened fire, did Myers’ battalions deploy from column into line. There ensued a series of ferocious firefights, which he says took place almost muzzle to muzzle, each being followed by a bayonet charge, in which several enemy battalions were routed in succession. Shortly after this he was shot in the thigh and was being helped to the rear when he noted, with horror, that only a third of the Fusiliers were still on their feet; notwithstanding, their remorseless advance continued.

For all that Napier’s version of the battle is burdened by his opinions on Beresford and flawed in some details, it contains the finest account possible of the Fusilier brigade’s counter-attack and its consequences. The epic quality of its prose cannot be equalled and, although it has been quoted in numerous regimental and campaign histories, this in itself justifies its being repeated here:

‘Such a gallant line, issuing from the midst of the smoke and rapidly separating itself from the confused and broken multitude, startled the enemy’s heavy masses, which were now increasing and pressing onwards as to an assured victory: they wavered, hesitated, and then vomiting forth a storm of fire, hastily endeavoured to enlarge their front, while a fearful discharge of grape from all their artillery whistled through the British ranks. Myers was killed; Cole, and the three colonels, Ellis, Blakeney and Hawkshawe, fell wounded; and the Fusilier battalions, struck by an iron tempest, reeled and staggered like sinking ships. Suddenly and sternly recovering, they closed on their terrible enemies, and then was seen with what a strength and majesty the British soldier fights. In vain did Soult, by voice and gesture, animate his Frenchmen; in vain did the hardiest veterans, extricating themselves from the crowded columns, sacrifice their lives to gain time for the mass to open out on such a fair field; in vain did the mass itself bear up, and, fiercely striving, fire indiscriminately upon friends and foes, while the horsemen hovering on the flank threatened to charge the advancing line. Nothing could stop that astonishing infantry. No sudden burst of undisciplined valour, no nervous enthusiasm, weakened the stability of their order; their flashing eyes were bent on the dark columns in their front; their measured tread shook the ground; their dreadful volleys swept away the head of every formation; their deafening shouts overpowered the dissonant cries that broke from all parts of the tumultuous crowd, as foot by foot and with a horrid carnage it was driven by the incessant vigour of the attack to the farthest edge of the hill. In vain did the French reserves, joining with the struggling multitude, endeavour to sustain the fight; their efforts only increased the irremediable confusion, and the mighty mass, giving way like a loosened cliff, went headlong down the ascent. The rain flowed after in streams discoloured with blood, and fifteen hundred unwounded men, the remnant of six thousand unconquerable British soldiers, stood triumphant on that fatal hill.’

Soult managed to form a grenadier unit into a rearguard which, together with the expertly withdrawn French artillery, covered the flight of his broken infantry across the stream and into the woodland beyond. The British, too exhausted and now too few in numbers, did not pursue. Elsewhere, two Portuguese batteries had come forward and begun to punch holes in Latour-Maubourg’s ranks while, closely followed by Harvey and Lumley, he sought to conform to the French withdrawal. Five of the KGL’s lost guns were recovered, although the battery’s howitzer had been towed away by the enemy. The Buffs’ Regimental colour was recovered by Sergeant Gough of the 7th Fusiliers and returned to its owners.

Alten’s Germans were ordered to retake Albuera village, which they did at some cost, and Hamilton’s Portuguese division assumed responsibility for the Allied right flank.

The day’s fighting had cost both armies very dear. Soult had sustained the loss of about 8,000 men killed or wounded, including 800 of the latter left on the field. His capture of a howitzer, several colours and about 500 prisoners, a surprisingly high number of whom escaped shortly afterwards, was hardly an adequate return for the loss of one-third of his army. He had failed to relieve Badajoz and he believed that he had been deprived of a well-deserved victory. There is no beating these troops,’ he wrote of the British after the battle. ‘I always thought they were bad soldiers – now I am sure of it. I had turned their right, pierced their centre and everywhere victory was mine – but they did not know how to run!’

Beresford, far from being elated by the sudden recovery in his fortunes, remained deeply despondent, a state of mind reflected in his despatch on the battle. Reading through it the following day, Wellington commented that another such success would ruin the Allied cause; then, conscious of the effect the despatch would have on those at home, he turned to one of his staff with the remark: This won’t do – write me down a victory.’

What depressed Beresford most were the crippling casualties sustained by the British portion of his army. The Germans and Portuguese had between them lost approximately 600 men, killed, wounded and missing; the Spaniards 1,368; but the British loss was in excess of 4,000. Brigades were coming out of action commanded by captains, battalions by subalterns and companies by sergeants and corporals; the following morning, it is said, one drummer collected the rations for his company in his hat. The grievous extent of the loss is set out below.

With the British completely exhausted and the Portuguese now holding the line, Beresford requested Blake for Spanish assistance in clearing the field of its thousands of wounded. It beggars belief that the Spaniard should have declined, commenting off-handedly that each of the Allies should be responsible for their own casualties. The result was that the wounded spent the night where they lay, drenched by continuous rain. As if they had not suffered enough, the scum among the camp followers and the local peasantry appeared after dark to strip and rob them, murdering any who dared to resist. Next morning, the field resembled a charnel house, the sights of which remained fixed forever in Captain Sherer’s mind:

‘Look around – behold the thousands of slain, thousands of wounded, writhing in anguish and groaning with agony and despair. Here lie four officers of the French 100th, all corpses. Here fought the 3rd Brigade; here the Fusiliers: how thick those heroes lie! Most of the bodies are already stripped; rank is no longer distinguished. Here again lie headless trunks, and bodies torn and struck down by cannon shot. Who are these that catch every moment at our coats? The wounded soldiers of the enemy, who are imploring British protection from the Spaniards. It would be well for kings, politicians and generals if, while they talk of victories with exultation and of defeats with indifference, they would allow their fancies to wander to the field of carnage.’

Among those lucky enough to have been brought off the field on the evening of the battle was Lieutenant Latham of the Buffs, unrecognisable but still incredibly alive and still with his King’s colour safe within his coat.

Beresford had expected Soult to renew his attack on the 17th but, to his intense relief, he did not and the following day the French withdrew. The siege of Badajoz was renewed although, for various reasons, neither it nor Ciudad Rodrigo fell until the following year.

There were many heroes at Albuera, but only a few survived to receive any reward. Major Guy L’Estrange, who had kept the 2/31st in action after the rest of Colborne’s brigade had been swept away, was awarded brevet promotion to lieutenant-colonel and presented with a commemorative gold medal by his brother officers. In due course he became a lieutenant-general and was knighted.

Lieutenant Matthew Latham also received a gold medal from his brother officers and, on learning of the manner in which he had come by his terrible wounds, the Prince Regent personally paid the cost of a surgical operation to repair the worst of the damage. In 1813 Latham was rewarded with a captain’s commission in a Canadian Fencible regiment but remained with the Buffs and exchanged back at the same rank the following year. He retired from the Army in 1820 with an annual pension of £100, plus £70 per annum on account of his wounds. Subsequently, his defence of the colour was permanently commemorated by the Buffs with a magnificent silver centrepiece depicting the event.

Lieutenant-Colonel Inglis, who had urged the 57th to ‘die hard.’ waited for two days before having the French grapeshot surgically extracted from his neck. After a spell of convalescent leave at home he returned to the Peninsula and took part in numerous hard-fought actions, ending the war as a major-general. ‘General Inglis,’ wrote Napier, ‘Was one of those veterans who purchased every step of their promotion with their own blood.’ In 1822 Inglis married at the age of 58 and had two sons, both of whom followed him into the service.

The carnage at Albuera also brought promotion to many other officers, since vacancy and merit also played a part in the system, and of course advancement in the careers of a much greater number of NCOs and private soldiers. As a reward for the outstanding leadership displayed by the NCOs during the battle Beresford allowed each battalion in Houghton’s and Myers’ brigades to submit the name of one sergeant for promotion to the commissioned rank of ensign; selection cannot have been a difficult matter, since so few were left to choose from.

The hardest-hit units, no longer able to function on their own, were formed into provisional battalions until their strength could be restored with reinforcement drafts. It would be two years before the Buffs and the 57th fought another battle. The 29th was sent home to recover and did not fight again during the war, arriving in Flanders just too late to participate in the Battle of Waterloo. The survivors of the 2/7th and 2/48th were absorbed by their respective 1st battalions.

Writing of the astonishing motivation that imbued the British infantry at Albuera, Sir John Fortescue commented: ‘Such constancy as was displayed by these battalions is rare and has seldom been matched in the history of war. Whence came the spirit which made that handful of English battalions content to die where they stood rather than give way one inch? Beyond all question it sprang from intense regimental pride and regimental feeling.’ True, but to that must be added additional interlinked factors such as the contemporary attitude to the French and the close bonds of comradeship. To give best to the French was unthinkable, and, if it valued its reputation, no battalion would leave the line while others were still in place; likewise, no man would leave the ranks while his comrades were still fighting, for he would have to face them afterwards. It mattered not that on this occasion the French, scenting an easy victory, were at their most formidable; rather the reverse, in fact.