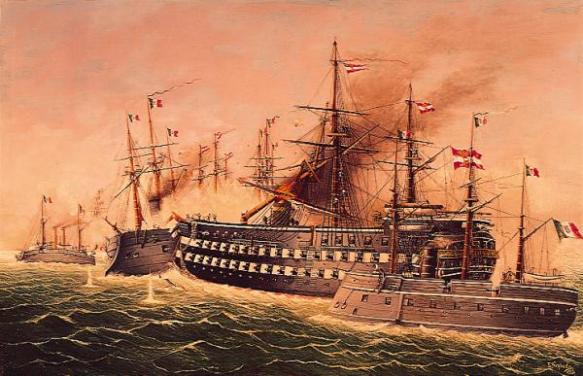

Eduard Nezbeda, ‘Die Seeschlacht von Lissa, 1866’. oil painting, 1911, private collection, Vienna. Portrayal of the Austrian triple-decker wooden battleship Kaiser (centre of picture) ramming the Italian ironclad Re di Portogallo. The Kaiser suffered substantial damage in the engagement. Reproduced in A.E. Sokol, Seemacht Österreich. Die Kaiserliche und Königliche Kriegsmarine 1382-1918 {Austrian Seapower: The Imperial and Royal Navy 1382-1918}, F. Molden, Wien, 1972.

‘Admiral Persano’, circa 1860. Contemporary photograph. Reproduced in Lamberto Vitali, Il Risorgimento nella fotografia {The Risorgimento in Photographs}, Giulio Einaudi editore, Torino, 1979, p.216.

Speaking to parliament in 1850, Massimo d’Azeglio observed that Piedmont was ‘an ancient home of honour, an ancient warrior country’. Although not much of a warrior himself, the prime minister understandably chose to emphasize his country’s military ethos. Turin was not an imperial capital like Rome or an artistic capital like Florence or a capital of a maritime republic like Venice. It was the most military city in Italy, capital of a country in which the army had for centuries been identified very closely with the state.

The Piedmontese were eager to continue this association when they formed the new Kingdom of Italy. Distinctions between civil and military were quickly blurred by the presence of twenty-five generals and four admirals in the new parliament, some of them as elected deputies, others as senators nominated by the king. The chiefs of the army and navy could be parliamentarians and even cabinet ministers. There was thus little time for them to do their jobs properly and no chance of political neutrality. In June 1866 General Alfonso Lamarmora was not only prime minister and foreign minister but also chief-of-staff of an army on the verge of fighting a war.

The officer corps of the Italian army was dominated by Piedmontese veterans eager to implant their particular ethos in the new force, many of whose soldiers came from despised areas that had traditionally produced poor fighters. Unfortunately the Piedmontese themselves seemed recently to have lost their fighting skills, and their generals were fusty and unimaginative men who distrusted flair and initiative (especially when displayed by Garibaldi) and relied too much on conventional tactics and use of the bayonet. A typical example was General Alfonso Lamarmora, who had been prime minister after Cavour’s resignation in 1859 and who was appointed again to the post in 1864. A commander with no sense of strategy, he was obsessed by drill and invariably hostile to innovation.

Lamarmora’s statue in Turin, soaring in one of the city’s finest squares, is an object so impressive that foreign visitors would be forgiven for believing that they were viewing a great conqueror, a sort of Piedmontese Hannibal. Like the Savoia, he rides a fine steed, and the plinth below him is decorated with lions’ heads and inscriptions commemorating his career. The general made his name by his rough suppression of the revolt in Genoa in 1849, an action which hinted that the Piedmontese, recently defeated by Austria, might be venting their frustration on one of their own cities. Having established his reputation as a tough and reliable soldier, Lamarmora was rapidly promoted and selected to lead the expedition to the Crimea, where his brother Alessandro, founder of the plume-hatted bersaglieri, died of cholera. As chief-of-staff in 1859, serving loyally if awkwardly under Victor Emanuel, he won the small Battle of Palestro before his army arrived too late to fight at Magenta and later performed poorly at San Martino. Shortly afterwards the king, who longed for his premiers to be pliant generals rather than difficult politicians, appointed him prime minister. Lamarmora then spent the next seven years in politics, a sphere where his lack of skills and vision were all too evident. In June 1866 he resigned his political posts to concentrate on his duties as chief-of-staff and travelled to Lombardy eager for the much-trumpeted ‘baptism of blood’. Almost everyone seemed confident of the outcome, partly because the Austrians were concentrating on Prussia and had only a small army in Venetia, a region they no longer wanted and had already offered to give up. Italy, by contrast, had been expanding its forces in recent years and could now outnumber its enemy by more than two to one for the contest which took place near Verona.

The second leading general in the campaign was Enrico Cialdini, a Modenese suspicious of Lamarmora and other Piedmontese generals, whom he regarded, in most cases rightly, as inferior commanders. He had served in Lombardy in 1859, but his earliest military experiences had been acquired in the fiercer circumstances of Spain’s first Carlist War in the 1830s. The invasions of 1860 and the savagery with which he overcame any type of resistance in the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies: the declarations of martial law, the burning of villages, the summary executions of peasants caught with weapons, the pitiless bombardments of Ancona, Capua and Gaeta. He treated the inhabitants of states with which Piedmont was not at war as if he were wreaking vengeance on a barbarous people rather than hoping to persuade them of the merits of Italian unification. For his role in expelling the Bourbons in 1861, he was rewarded with a dukedom, as if to imply that as a commander he ranked alongside Marlborough or Masséna, Duke of Rivoli. Soon afterwards he returned to Naples as the king’s lieutenant-general to deal with the civil war his actions had done so much to promote.

In the summer of 1866 the Italian army was divided: Lamarmora had the bulk of the army in Lombardy; Cialdini commanded a substantial force at Bologna; and Garibaldi led his volunteers in the Alpine foothills. This arrangement, a consequence of the jealousy and distrust among senior generals, made cooperation difficult. Lamarmora met Cialdini to discuss the campaign but failed to establish a joint plan. In the event he advanced without waiting for the others and marched his troops towards the fortresses of the Quadrilateral. Believing the Austrians to be east of the Adige, he crossed the River Mincio without making an effort to reconnoitre. He was thus astonished to discover, on the east bank of the Mincio, an Austrian force, which attacked his advance guard at Custoza and drove it back. Giuseppe Govone, the best of the Piedmontese commanders, counter-attacked with his division and regained some ground but could not retain it without reinforcements. Desperately he appealed to the general to his rear, Enrico Della Rocca, to send his fresh divisions to the front, but his colleague refused to help. More of a courtier than a soldier, Della Rocca stuck to earlier orders from Lamarmora instead of following the elementary military rule of marching to the sound of gunfire.

Throughout the day Lamarmora himself panicked. His army was strung out over a considerable distance, and he galloped madly from one unit to another so that his subordinates were seldom able to find him; for some reason, inexplicable even to himself, he ended the fight about thirteen miles from the battlefield. A message was sent from the king to Cialdini ordering him to come to the rescue, but the general refused; he had in any case been positioned too far away to reach the battlefield in time to affect the result.

Both the senior generals mistook a reverse for a rout and chose to retreat. Yet Cialdini could have led his men towards the Po and threatened the Austrian flank, and Lamarmora could have regrouped on the Mincio and counter-attacked with the divisions that had not fired a shot during the battle; he had lost fewer than 1,000 men at Custoza, and his army was still far larger than the enemy’s. His excessive and unnecessary retreat – the Austrians were not even pursuing him – added embarrassment to the humiliation of the defeat and deepened the demoralization of a nation that had been told victory was inevitable. The actions of Lamarmora, Della Rocca and perhaps Cialdini deserved examination before a court-martial. None of them faced one. Instead of being condemned as the incompetent general that he was, Lamarmora was posthumously rewarded with the magnificent statue in Piazza Bodoni.

Turin’s military monuments were not all erected to commemorate individual kings and commanders. Some of them are collective memorials, representing units of the armed forces, principally the bersaglieri (who are always shown running) but also the cavalry, the carabinieri and the Alpine regiments. Only one monument, that dedicated to the men who went to the Crimea, contains a statue of a sailor.

Piedmont had no nautical traditions; indeed, until it was given Liguria by the Congress of Vienna, it possessed no coastline except around Nice. Its insignificant navy did little in the early wars of the Risorgimento and was never required to fight a proper battle. United Italy, however, had an extremely long coastline. Since it also had aspirations to join the Great Powers, it set about building an impressive fleet, though its only plausible enemy was Austria, which had little naval history or ambition of its own. By 1866 this new fleet included twelve new ironclads and was commanded by an admiral, four vice-admirals and eight rear-admirals. The Austrian navy was smaller, slower and less well equipped: it possessed only seven ironclads. The Italian force was thus superior in all material respects though generally inferior in most human ones, most markedly in the abilities of the admirals in command.

The Italian commander was Carlo Pellion, Count of Persano. Unlike Garibaldi, who was a seaman both by birth and by aptitude, the Piedmontese Persano had seafaring neither in his blood nor in his upbringing. He came from the inland rice-growing area of Vercelli and was apparently unable to swim. Some people believed he chose to be a sailor because there was so much less competition for posts in the navy than there was in the army. He himself owed his very rapid promotion not to his exploits but to his talent at flattery, intrigue and making himself popular at court. He managed to ingratiate himself with Cavour and became an unlikely friend of Azeglio, possibly because that amorous statesman was attracted to his English wife. A vain and quarrelsome individual with a taste for fighting duels, Persano was both frivolous and irresponsible: he once asked Azeglio, who was prime minister at the time, to give him a false passport so that he could pursue a ballerina in Austrian-held Milan. His friend refused to help.

Persano’s seamanship could be embarrassing. In 1851 he ran his ship aground outside Genoa harbour when carrying Piedmont’s contribution to the Great Exhibition in London. Two years later, even more embarrassingly, he ran aground again, this time while transporting the royal family to Sardinia for a hunting trip; apparently he was trying to take a short cut and hit some rocks that were not marked on his charts. Although he was arrested and reduced in rank for six months after this episode, the setback did not harm Persano’s career. In 1860 Cavour entrusted him with the job of shadowing Garibaldi and stirring up trouble in Palermo and Naples, and in the autumn of that year Persano assisted Cialdini in the capture of Ancona by bombarding the papal port from the sea. Over the next two years he became a parliamentarian, the minister of the navy and the admiral who in 1866 found himself in charge of the fleet at Ancona under government orders to defeat the Austrians and rescue Italy’s reputation after the fiasco of Custoza.

Persano was not, however, eager for combat and, although he had only brought his ships up from Taranto, claimed that they needed an overhaul. To repeated orders from Agostino Depretis, the current naval minister in Florence, he responded with a range of reasons for delay: the fleet was not ready, the crews were not trained, water had got into the cylinders and something was wrong with the coal; most important of all, the Affondatore (the Sinker), the best and newest ship, was still on its way from England, where it had been built. When Depretis told him to make himself master of the Adriatic, Persano replied that he had no proper charts of the one conceivable sea where his navy might fight. While the fleet was still being overhauled after its voyage from Taranto, the audacious Austrian admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff appeared with his navy off Ancona, fired a few salvoes and waited for the Italians to come out and engage him; when they remained in port without returning fire, he sailed away and claimed a moral victory.

An exasperated government eventually used the threat of dismissal to force Persano out and attack the island of Lissa off the Dalmatian coast. The navy was duly shelling the Austrian batteries on the island and preparing to land its troops when Tegetthoff reappeared and made a reckoning unavoidable. While Persano was organizing his line, the long-awaited Affondatore steamed up, its arrival persuading him to abandon his flagship, the Re d’Italia, and direct the battle from an armour-plated turret on the new vessel. Most of his captains were unaware, however, of the changeover and continued to look for signals from the Re d’Italia – until it was rammed and sunk by Tegetthoff’s own flagship. The simultaneous loss of another ship, which caught fire and exploded, convinced Persano that the battle was lost, even though he still easily outnumbered the Austrians and could have carried on the fray. Like the generals at Custoza, he converted a setback into a disaster and, as with Lamarmora, ordered an unnecessary retreat, leading his ships back to Ancona, where expectant crowds were waiting to cheer captured Austrian vessels.

Lissa ended the career of Persano, who was accused of cowardice but cashiered for the lesser sins of negligence and incapacity. The defeat had other repercussions, especially for the future of the Italian navy, which henceforth tried to avoid battles on the open seas; one consequence of this was the disaster of November 1940, when the British disabled half the fleet that lay anchored in the harbour of Taranto. Yet the most insidious effect of the 1866 war was its impact on the psyche of the Italian nation. The very names Lissa and Custoza became reproaches, incitements to redress and redemption. Instead of persuading Italians not to attempt to become a Great Power, they encouraged them to try even harder. As Austria seemed the obvious place to seek such redemption, Victor Emanuel suggested to Bismarck in 1878 that a joint attack on the Habsburgs would give each of them victory and new territory. When the chancellor replied that Germany was big enough already, Italy abandoned the idea, became an ally of Austria and embarked on colonial adventures in Africa. Yet the defeats of 1866 rankled and continued to do so well into the twentieth century. The obsession with amends was a fundamental motive in the decisions to take part in the world wars in 1915 and 1940.