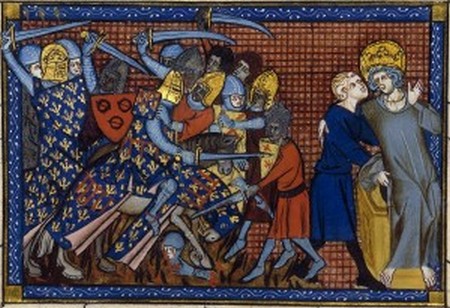

Battle of Al Mansurah.

The Battle of Al Mansurah was fought from February 8 to February 11, 1250, between Crusaders led by Louis IX, King of France, and Ayyubid forces led by Emir Fakhr-ad-Din Yusuf, Faris ad-Din Aktai and Baibars al-Bunduqdari

The town of Mansurah (mod. El-Mansûra, Egypt) was founded by the Ayyūbid sultan al-Kāmil (1218–1238) as a forward military base against the Fifth Crusade (1217–1221), which in November 1219 had seized the vital port of Damietta at the mouth of the eastern branch of the Nile following a prolonged siege.

Mansurah was, in fact, a large fortified encampment of a type typical in Middle Eastern Islamic warfare. Its location also dominated the eastern Nile and the Bahr al-Saghir, a strategic waterway linking the Nile and Lake Manzala. After a long pause, largely caused by the divided leadership of King John of Jerusalem and Cardinal Pelagius, the crusader army advanced along the eastern bank of the Nile in July and August 1221, heading for Cairo. It was, however, halted by the Ayyūbid forces at Mansurah, and al-Kāmil ordered that the irrigation dykes be broken, and the surrounding land flooded. The crusader army found itself caught on a small island between the eastern Nile and the Bahr al-Saghir and was obliged to negotiate a humiliating peace. However, in return for the surrender of Damietta, still held by a crusader garrison, the trapped army was permitted to retreat in safety at the end of August 1221.

In 1249 Damietta again fell to a crusade army, led by King Louis IX of France. Although he was dying, the sultan al-Kāmil (1240-1249) assembled an army at Mansurah, supported by a river fleet. In November. December 1249, the crusaders advanced up the Nile toward Mansurah. The death of al-Sālih on 23 November was kept a secret from his army, which skirmished with the crusaders outside the town during December and January. Eventually the crusaders crossed the Bahr al-Saghir to attack the town, but on 11 February 1250 the king’s brother Robert, count of Artois, disobeyed orders and entered Mansurah, where he was defeated in street fighting. The Egyptians then counterattacked, and the crusaders were besieged in their camp, while the Egyptian river fleet won control of the Nile. In March and April the crusaders retreated toward Damietta before being forced to surrender near Fariskur, where King Louis was taken prisoner. In May 1250 some senior crusader leaders were released after paying large ransoms, but much of their army was enslaved.

This second battle of Mansurah was one of the most important during the entire crusades, confirming three strategic points: that Egypt was the center of Islamic power in the Middle East, that Frankish power in the Holy Land could only be preserved by dominating Egypt, and that the conquest of Egypt by a seaborne assault was probably impossible, given the military technology of this period. The Ayyūbid sultanate collapsed during this campaign, to be replaced by a military regime, which evolved into the Mamlūk sultanate. Victory at Mansura gave the Mamlūks great prestige, helping them to inflict a major defeat upon the invading Mongols a decade later.

The Mameluk coup d’etat, St Louis is watching in prison. One third of France’s entire annual revenue was paid as ransom for Saint Louis and those of his men who were taken captive. The Mamluks had assumed power in Egypt after a bloody coup d’etat and allowed the king to go to Acre, still the de facto capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, where he met with his queen, Margaret of Provence, after her flight from Egypt with her son, born a day days after the Battle of Fariskur. Margaret had aptly named the infant Jean Tristan. While Tristan probably means “clanking swords” in the old Welsh, Cornish and Breton sources of the famous tale, it was interpreted as “sadness” in the courtly culture of the High Middle Ages. Louis remained in the Holy Land for four years, strengthened what was left of the defences of the Crusader principalities after the defeat at La Forbie, dabbled in the intricate politics and diplomacy of the Near and Middle East, but was at least rewarded with an elephant and a zebra by Aybak, the Mamluk sultan of Egypt when he refused a new alliance with the Syrian Ayyubids.

Louis IX’s Crusade

Hopes for the recovery of Jerusalem were vested in the king of France, Louis IX after the expiration of Frederick II ‘s treaty with al-Kāmil, the Ayyūbids moved to occupy Jerusalem. The Capetian kings of France had a tradition of crusading, but they were also known as hard-headed and practical men of affairs. The leading French historian of Louis IX, Jean Richard, has argued that he did not make a decision to go on crusade without overcoming a certain reluctance on his own part as well as the opposition of his mother, Blanche of Castile. What decided him was a serious illness that nearly cost him his life. Once determined, he set himself to the task with great energy. He entrusted the government of the kingdom to his mother and devoted himself to raising the required funds and making the necessary preparations. Although he worked with the pope, Innocent IV, the entire initiative was in his hands. The thoroughness of his preparations is demonstrated by the fact that he improved the Mediterranean port of Aigues-Mortes to serve as a point of departure and made arrangements for supplies to be stored in Cyprus. His objective was Egypt, and specifically the same port of Damietta that had been attacked by the Fifth Crusade.

Although Louis’s crusade was preached in various countries, it remained a French enterprise. Louis’s army was not large, but it was quite respectable in medieval terms. Louis spent about six times his annual income on the crusade, but most of the money came from nonroyal sources. He left for the East on 25 August and landed near Damietta on 5 October, meeting almost no opposition. The garrison of the city fled, leaving it open to him. He immediately took over the city and made preparations to move inland. Some thought was given to the capture of Alexandria, but this was rejected in favor of an attack aimed at Cairo. On 20 November Louis moved south along the east bank of the Nile toward Mansurah. There the army stalled, unable to cross the canal that lay in its path, until a secret crossing place was made known to them. The king’s brother Robert of Artois led an advance guard across the canal but rashly attacked the Muslim camp. Louis, who crossed to aid his brother with the bulk of the army, was stymied by the arrival of the Ayyūbid sultan with reinforcements. Forced to retreat, he suffered heavy losses and had to surrender. Louis was ransomed, but Damietta was once more returned to the Egyptians. Louis left for Acre, where he devoted himself to improving the coastal fortifications of the Latin kingdom.

Perhaps more than any previous crusade, Louis’s expedition showed the magnitude of the task confronting those who desired to liberate the Holy Land. When the king returned home in 1254, he had accomplished little more than repairing some of the damage resultant from his failure at Damietta. He had not, however, lost his sense of commitment to the crusade, which, if anything, had been reinforced by the increasing depth of his personal piety.

Bibliography Donovan, Joseph P., Pelagius and the Fifth Crusade (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950). Gottschalk, Hans L., Al-Malik al-Kamil von Egypten und seine Zeit (Wiesbaden: Harassowitz, 1958). Humphreys, R. Stephen, From Saladin to the Mongols (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977). Irwin, Robert, The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamluk Sultanate 1250–1382 (London: Longman, 1986). Powell, James M., Anatomy of a Crusade, 1213–1221 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986). Richard, Jean, Saint Louis: Crusader King of France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Strayer, Joseph R., “The Crusades of Louis IX,” in A History of the Crusades, ed. Kenneth Setton, 2d ed., 6 vols. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969–1989), 2: 487–508. Van Cleve, Thomas C., “The Fifth Crusade,” in A History of the Crusades, ed. Kenneth Setton, 2d ed., 6 vols. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969–1989), 2:377–428.