The following is from an account by another soldier, simply identified as ‘M’:

At last the time has come, and we set off to conquer the enemy positions, which don’t offer any resistance, and the few men who are still alive come out of their holes crying, ‘KAMARAD!’

The artillery lengthen their range, one hundred metres by one hundred metres, so we continue to advance behind the wall of fire and in this way we arrive at the first line; from there, after a short five-minute breathing space, we start off again for the assault on the second line, which is the goal indicated by the General of the Division.

There, as at the first line, the enemy don’t put up any resistance.

Arriving in the line, we begin to dig some small holes to allow us at the same time to keep out of sight of the enemy, and to take cover from his artillery. The day passes like this, at night everyone works and keeps watch at the same time, and we carry on like this right up to the evening of the 25th, without being disturbed by the enemy.

Weariness begins to make itself felt, the water-bottles are empty, and the water fatigue parties don’t arrive, but all the same we put up with it in the hope of being relieved next day in the evening.

Everything adds to our misery. At eight o’clock big drops of rain begin to fall, the earth gets slippery and fills our trench with mud; on the other hand, this water, collected so preciously in our mugs set up on the parapet, this water will serve to moisten our parched lips, and in this way the night passes right up to dawn on the 26th.

At dawn the clouds begin to break and the sun appears at several points; our planes take advantage of this in order to fly over the enemy lines; the German pilot doesn’t stay inactive, and signals our new positions to his artillery. Besides this, towards 6 o’clock the shells from our guns of all calibres begin to fall around us.

At 2 o’clock, in spite of this terrible bombardment the losses are minimal, but at that very moment the missiles fall exactly in the trench; to the left of my section someone tells me that there are already several victims, but there’s not even time to ask the names of his comrades before a large-calibre shell comes exploding in the midst of us.

I feel myself struck down, this time I realise that I’m seriously injured, a wound no doubt grave grips me as if in a vice in the abdomen, and I’m certain, too, that I’ve lost all use of my right arm.

Gathering my strength, I lift myself up and look around me; my two corporals who were there have been struck down dead.

The horror of the spectacle gives me back more strength. And without caring about the consequences I drag myself painfully to the First-Aid Post. where the medical orderly immediately gives me the first attention which my condition requires.

At 5 o’clock the difficult transport of the wounded begins; the work is hard for our stretcher-bearers who are carrying us away.

At last, here we are, arrived at the first halt, the battalion First-Aid Post; there, I’m going to pass the night.

Early the next day, other stretcher-bearers come to take us and transport us to a second Aid-Post, and in this way from Aid-Post to Aid-Post we are transported right to Marceau Barracks.

From there we are transported in lorries, only a short distance; at the end of ten minutes we’ve arrived at the field hospital at Dugny. Straight away they take me into the operating room; the doctor encourages me by saying that I’ve had a bit of luck, that the wound in my abdomen, which he himself thought serious, is very light.

The same evening, I’m selected to be transported to the rear. I’m taken by lorry all the way to Souilly where I’m put on a hospital train, and from there I’m de-trained at Revigny, where I’m detailed for the English Hospital at Faux Miroir, where I am at the present time surrounded by the greatest care of the staff.

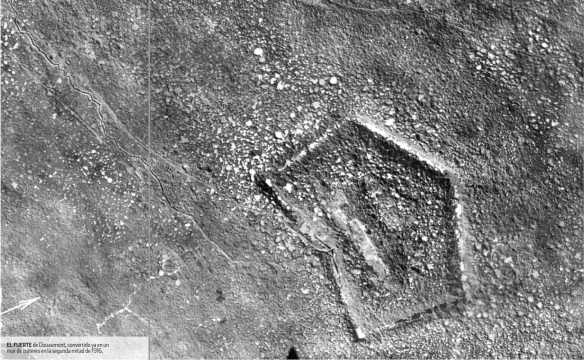

Both accounts have that closeness of vision of the fighting man caught up in the mêlée – the ants in the anthill. But the seizure of Douaumont could seem almost an experience on a mystic level for those not involved in the cut and thrust of action and thus able to understand the significance of what was taking place. Thus Lieutenant-Colonel Picard, rounding off his description of the fort’s seizure, was moved to write:

When victory, with her great luminous wings, touches the soul of a combatant, there is such an intoxication, so noble a pride that nothing, nothing, not even glorious death on the field of battle, could equal the happiness of living through such a time!

If the early phase of the battle had been observed by a distinguished British commentator in the person of H. Warner Allen, the later phase saw a visit by the well-known war correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, famous for his eye-witness reports from Gallipoli the previous year. Travelling with five other members of the British and American press, he reached the city on the day before the offensive against Douaumont. The party’s first visit was to the Citadel, where they were shown ‘every single detail of this wonderful underground fortress’; one detail which particularly impressed him was the fact that 30,000 loaves of bread were baked daily within the Citadel for its huge, constantly changing garrison. They were then entertained to a meal by the city’s military governor, General Dubois: ‘a really wonderful lunch beautifully cooked by a prize chef and washed down with some of the finest wines of France. This kind-hearted officer had actually sent all the way to Bar-le-Duc for luxuries such as cakes and pastry for which the town is famous.’ There followed a guided tour of the city streets, to be shown, again ‘in very great detail’, the steps which had been taken for the door-to-door defence of Verdun should such a contingency have arisen: ‘The scheme was to turn every single house – or rather cellar – in which the place abounds, into a separate fort, and each was to be defended à outrance.’

But the prime focus of their visit was the real fort they knew was about to be attacked and whose recapture would give them the story that would make their journey worthwhile. On the following afternoon, the 24th, having been taken to a suitable vantage-point at the Fort de la Chaume, on the left bank of the Meuse, they were able to observe, if from some distance, the actual moment of victory:

At about 3 p.m. the weather lifted somewhat and the sun made a brave effort to come out. Thus we were able to witness the final stages of the advance against Douaumont. One could watch the tremendous curtain of artillery fire creeping slowly up towards it. Suddenly some red rockets flashed skywards through the gloom. This was the prearranged signal that the fort had been re-won.

The event moved Ashmead-Bartlett to remarkable heights of eloquence:

Thus was accomplished the crowning moment of the war, perhaps of all history. The French army of Verdun – exhausted and useless, according to the enemy’s reports – retook in seven hours, without withdrawing a man or a gun from the Somme, practically the whole ground which the Crown Prince’s army was only able to gain and hold at a cost of roughly half a million of the best German troops, and by the expenditure of an unprecedented quantity of material and ammunition.

But the most memorable event of their tour was yet to come: a visit under escort to the actual fort, before the fighting was entirely over and while the area was still under fire from enemy guns. German signs were still in evidence in the galleries but it was now fully garrisoned by the French – in fact with Chasseurs like the doughty soldiers who all those months before had fought with the late Colonel Driant. Ashmead-Bartlett noted the long vaulted chambers radiating from the galleries used as barracks, each containing double rows of wooden bunks: ‘Inside you see hundreds of warriors off duty rolled in their blankets asleep.’ But what he was most eager to see were the signs of the recent successful attack:

Especially interesting was the spot in the upper galleries where 400mm shells had entered. Dawn was breaking and the pale light was shining through this arch cut out of the solid concrete by these heavy shells. Sentries stood guarding the aperture which was rapidly being put in a state of repair. You look out and beyond on to a sea of huge shell craters. There are no luxuries or comforts of any sort for the garrison, for it has only been possible to carry up the bare necessities of life and a reserve supply of ammunition. I made my way through all these long galleries, damp, cold and filthy and studied the heroic defenders. They are great fellows, these Chasseurs. They are cold and caked with mud and weary from the incessant labour of carrying up supplies, but ever determined and indomitable. They have got back the fort and will never give it up again.

Summing up his whole visit to the Verdun sector, Ashmead-Bartlett wrote, in terms that can only have been music to his French hosts:

The battlefield of Verdun has a different atmosphere from any other I was ever on. Its horrors are also greater. But withal there is a feeling of intense satisfaction. You recognise the completion of a great masterpiece. You feel, as you so seldom have the chance of feeling in this war, that something vital and decisive has been accomplished, and that the work can never be undone… It was at Verdun that the French people found themselves again, and emerged from the clouds which have hung over them for forty-five years.

When the French took back Douaumont fort they also reclaimed Douaumont village. The regiment that seized it had among its members the soldier-priest Pierre Tailhard de Chardin, though his battalion was in reserve for the actual attack. ‘The colonial troops of my brigade captured the strong-point.’ he wrote to his cousin a few days later. ‘You see that we had our share of the glory, and that almost without loss, at least during the attack itself.’ The next morning, at dawn, they moved forward to a position on the ground gained: ‘I must say that that was not the best moment. I spent a most unpleasant day with my C.O. in a shell-hole just by Thiaumont farm, under a long-drawn-out continual bombardment that seemed to want to kill us off piecemeal. Such hours are the other side of the glory of attack.’

He attempted to describe his impressions, acknowledging ‘a sort of depression and inertia, partly due to the not very active part played by my unit. Fortunately this lack of activity, this lack of “go”, were put right by the stimulus of having plenty to do. All the same I didn’t feel that my spirit was really heroic.’ So much for himself, but contemplating the surroundings and the circumstances produced a strangely exhilarating response, though the awareness of the underlying tragedy of it all was never far off:

From a more speculative, almost ‘dilettante’ angle, I profoundly enjoyed, in short bursts, the picturesque side of the country and the situation. If you forget that you have a body to drag over the mud like a snail, the Douaumont area is a fascinating sight. Imagine a vast expanse of grim, naked hillsides, wild as a desert, more churned up than a ploughed field. All this we recaptured. I saw again the places where, in August, I huddled in holes that I can still distinguish – and in which my friends fell. Now one can make one’s way over them without fear: the crest above, and two kilometres beyond it too, are now held by us. Hardly any traces of the Boche can be seen – except round certain shelters, some appalling sights that one looks at without turning a hair: everything has been buried by the shells. To get back to the rear for rations you have (until some communication trenches have been contrived) to make your way for three-quarters of a kilometre across this chaos of enormous shell-holes and treacherous patches of mud, following a few makeshift tracks…

A few concrete pillboxes were still standing, marking the painful route. You can’t imagine how odd it was to see these shelters lost in the chaos of the battlefield, particularly at night. Just as in the inns along a main road or the mountaineers’ huts among the glaciers, a whole motley population of wounded, stragglers, somnambulists of all sorts, piled in, in the hope of getting a few moments’ sleep – until some unavoidable duty or the angry voice of an officer made a little room – soon to be occupied again by some new figure, dripping, wet and apprehensive, emerging from the black night…

All these horrors, I should add, are to me no more than the memory of a dream. I think that you live so immersed in the immediate effort of the moment that little of them penetrates to your consciousness or memory. And on top of that the lack of proportion between existence on the battlefield and life in peacetime (or at any rate in rest billets) is such that the former, looked back on from the latter, is never anything but a fantasy and dream.

And yet the dead – they’ll never wake from that dream. My battalion had relatively few casualties. Others, on our flank, were more unlucky. The little White Father who went to see you at the Institute last February, was killed. Pray for him. Now once more I’m the only priest in the regiment.

The Douaumont battle produced its huge crop of fatalities and, inevitably, its greater number of wounded. Among the staff at the British Urgency Cases Hospital at Revigny coping with its influx of casualties was a senior colleague of Nurse Winifred Kenyon, Sister S.M. Edwards. She wrote a description of her experiences at this time which would eventually appear in the Faux Miroir house magazine under the title ‘Thoughts of a Night Sister’. Her account, which shows how many and varied and from what different backgrounds were the patients who came under the hospital’s care, is perhaps all the more effective for being written in the third person, almost as though it were a scene from a novel. But though she wrote with style, she wrote with much compassion:

The Surgeon has done his last round, and with a cheery ‘Goodnight,’ is gone. Sister stands at the door of the ward till his footsteps have died away. One by one the lights of the château, gleaming through the trees, go out and, save only for the glimmer of light from the huts and the shining stars above, the place is wrapped in darkness. With a shiver, for the nights are cold, she turns and enters the ward. She passes from bed to bed, giving a drink here, smoothing a tossed pillow there, tucking up as she would a child some brave fellow who has just come through the horrors of those hideous slopes on which for nine months the battle of Verdun has raged. All then being quiet, she sits by the little iron stove, trying to keep warm this bitter winter night, and as she sits she listens, and she thinks.

She hears the muttered, half-broken sentences of the men as they toss and turn in their restless sleep, and she thinks of the sons of France lying there suffering ‘pour la Patrie’. She thinks of No. 20, from far-off Brittany, his face rugged like the rugged rocks of the coast on which he has weathered many a storm. Now he has weathered his last and most terrible storm, the storm of battle. She thinks of No. 12, who has come from the heights of Savoy. Frightfully crippled he lies there, for the deadly gas gangrene has done its fearful work, and never again will he climb his beautiful mountains. He stands on the threshold of life only. ‘Oh! C’est triste la guerre’ – that is all they say, these men: ‘It is so sad, this war.’ A wonderful spirit, this spirit of France. Yes, it is many of her men who are gathered here; for here are men from the fields of Normandy; from the sunny skies and orange groves of the Côte d’Azur; from the vine-clad slopes of the Pyrenees; and from farther still have they come; for there lies Abdallah from far-away Tunis, and Bamboula from still farther Senegal. Again she listens, and she thinks.

She hears the cannon booming. How near it sounds in the stillness of the night. How it makes the hut rattle and shake. She thinks of the terrible destruction that is being wrought by the hand of man on God’s beautiful earth. She thinks of the men who, away in the firing line, where terror and desolation reign, are veritably passing through hell. And she asks the unanswerable question, Why should such things be?…

She hears the rumble of heavily laden trains, as they pass without ceasing up to the front with their load of men and ammunition, to be hurled against the might of Germany. And she thinks of the indomitable heroism and endurance which have withstood that might all these long months, and her heart is filled with gratitude and admiration. Again she listens, and she thinks.

The wind is rising, and she hears it sighing in the pines, and it is as if it were the Voix de Morts – the voices of the dead – pleading for their sacrifice not to be forgotten, and she thinks of those brave men who have passed through those pines to their last resting-place. She thinks of the little wooden crosses she sees everywhere in this sad corner of France – in the fields, in the woods, in the gardens – and she asks, ‘Is it in vain they have died?’

‘Ma Soeur, ma Soeur!’ ‘Sister, sister!’ Sister is roused from her reverie. It is No. 8 – Bébé he is called, because of his curly hair and youthful spirit. He has been dreaming. He had lost his regiment and was struggling to find it again. A reassuring word, a ‘Quelque chose à boire’ – ‘something to drink’ and he is soothed to sleep once more.

The long night has passed. They are all awake now, and how bright and jolly they are. ‘Bonjour, ma Soeur, bonjour,’ resounds from all sides, and ‘Bonjour, tout le monde,’ replies Sister as she hurries round, getting them ready for their breakfast. Brave, cheerful fellows. It is the lasting memory of the ‘blessés’, with their child-like simplicity, their good humour and their patient endurance, that Sister will carry back to England with her from a hospital ‘somewhere in France’.