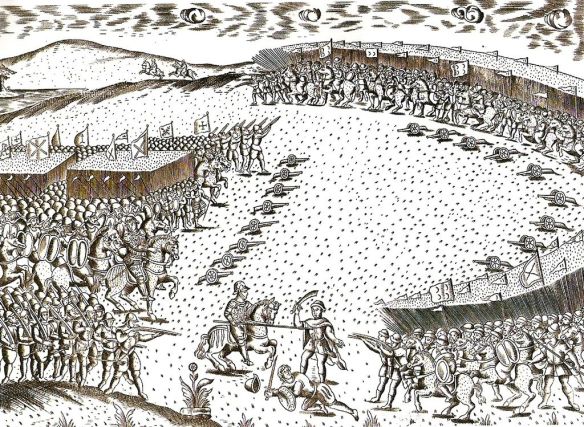

Battle at Ksar el Kebir, depicting the encirclement of the Portuguese army on the left.

The young king who led them into battle that day was like a vision from the dream chronicles of Christendom. A second Alexander, he was escorted by all the great lords of Portugal, the royal standards fluttering in the morning breeze at the head of a mass of silken pennants decorated with the heraldry of a worldwide empire. Like holy relics, King Sebastian wore the helmet of King Charles V and carried the sword of Prince Henry the Navigator into battle. A close escort was formed from the mounted troopers of the Tangier garrison, the most battle-hardened and experienced of all the army. The King rode up and down the lines, greeting his officers by name and saluting his soldiers.

Throughout the morning the cannon of the two armies spoke but it was only in the hour before noon that they drew close enough to find each other’s range. Then, as if by prearrangement, the entire Crusader army sank to its knees one last time in prayer. When they rose they chanted the battle cry of ‘Avis e Christo’. Despite the defensive arrangement of the square, Sebastian knew that he must strike hard and decisively if he was not to be overwhelmed by the enemy’s superior numbers. So, instead of standing ready and waiting, the crack troops that held the front of the Portuguese square advanced through their screen of cannon. Then they flung themselves on the centre of the Moroccan army, breaking the first Moroccan division, the Andalusians, who attempted to stand their ground. This brave frontal assault was blunted by a counter-attack by the second Moroccan division (largely composed of renegade Moors), who were in turn attacked by the crack Castilian regiments lent by King Philip. As the disciplined infantry of the two armies locked themselves in ferocious conflict, vast fields of Moroccan horsemen began to move across the surrounding plain, ready to launch the first attacks on the flanks of the Portuguese square. Like a river in spate, wave after wave of tribal cavalry descended from the hills, surrounding the whole Portuguese position and cutting them off from the ford and the road to the coast in a flood tide of horsemen.

As if in direct reply to this threat of annihilation, Sebastian launched his own surprise cavalry attack. His infantry regiments parted to allow the Duke of Aviero and the cavalry of his native ally, the deposed Sultan Muhammad al-Mutawakkil, to strike at the very centre of the Moroccan army. It was a near-suicidal charge, but if they had managed to kill Abdul Malik in clear view of his own troops they would yet have changed their fate that day. Their ferocious impetus allowed them to cut through the lines of Moroccan infantry and hack their way to within a few yards of Abdul Malik’s pavilion. For a few critical moments all hung in the balance. Two of the five royal standards of Morocco were felled by the assault but the bodyguards succeeded in holding the ground around the person of the Sharif. Then, just as suddenly as it had been launched, this audacious frontal attack was destroyed as vast numbers of Moroccan cavalry swarmed in to rescue the Sultan. It may have been at this moment that the Moroccan cavalry first became aware of supernatural support. The patron saint of the fallen Muslim city of Ceuta, Sidi Bel Abbes, was seen mounted on a grey horse, moving from tribe to tribe, encouraging them in their patriotic fervour. In the words of al-Ifrani, ‘Such things are not to be disbelieved, for it is known that the martyrs are ever living in God’s presence.’

The Crusaders’ assaults of the morning, first of infantry and then of cavalry, had been blunted and the latter overwhelmed. Yet on the ground lay proof of the ferocity of these assaults, for some two thousand Moroccan infantrymen, the disciplined cream of the army, lay dead on the field. The Crusaders now withdrew to take up their positions in defence of the original square. The field artillery of both sides had been silenced by the vicious fighting at the centre. Spiked, carriage-less or disabled, their tactical role was over and the battle took on a new shape. Throughout the long afternoon wave after wave of Moroccan cavalry launched themselves against the Crusader square. They were relentless in their courage, for where pikemen held their ground with arquebusiers embedded in the ranks, the defenders could cut lethal swaths through the ranks of the attackers.

But it was the attacks of the Sharifian regiment of dragoons, the mounted arquebusiers, which proved decisively effective that day. They were recruited from members of the Jazuli brotherhood and the Haha tribes who had formed the original core of the Sharifian army. They had been trained to discharge their weapons in the face of the enemy at the culmination of a gallop, and their horses were trained to pirouette just a few paces away from the lethal spikes of the Christian pikemen, allowing their riders to fire at point-blank range at the enemy and then double back out of danger, to reload in safety and prepare for the next attack. At first Sebastian took his place in the front rank of the front line at the centre of the square. Then he could be seen moving from regiment to regiment to inspire his men to hold their line. Three horses died beneath the King that afternoon and his magnificent bodyguard was cut down to a bare seven men.

It was the inexperienced Portuguese peasant recruits who held the rear of the square who broke first, their spirit having collapsed after the death of their valiant commander, Francisco de Tavara. But Sebastian was quick to react. He gathered together the last remnants of the Crusader cavalry and led three separate counter-attacks against the Moroccans in an attempt to give his men the opportunity to re-form their line. But it was not just at the rear that the square was crumbling. The ceaseless attrition of the mounted dragoon attacks had also broken its way through even the front line. Moroccan cavalry now poured into the centre of the square. Once they were attacked from both the front and the rear it was over for the Portuguese regiments. They retreated from their positions and fell back to the shelter of the wagon train. Effective resistance then crystallised around the sturdy German pikemen, the soldiers of Castile and the Portuguese noble-men, who alone held their positions. The last hours of the battle were long and drawn out, for the Moroccan army had started pillaging the wagon train and the victorious soldiers were now more interested in taking captives to be ransomed than in adding another corpse to the carnage of the day. In the last hour of dusk the surviving knots of Crusader resistance were subdued by the Moroccan cavalry. The Germans held their position to the end, disdaining all offers of surrender. As the sun set they were overwhelmed in one last massive cavalry charge and as the darkness thickened not a single Crusader soldier was left standing.

Of the twenty-six-thousand-strong army that had stood to arms that morning, fewer than one hundred would reach the safety of the coast. The rest were either dead, dying or captive. It was the most decisive battle of an age that was otherwise dominated by the gradual attrition of siege and counter-siege. It was the very last battle of the Last Crusade. Although it was the end of an era, it was also very much of the past: a day when monarchs led their men to war, when three kings would be counted among the tens of thousands of dead. It was a day of exhilarating bravery, where both armies displayed the utmost courage and resource. The battle had been won by the glory of the cavalry charge, and the role of artillery, the murky pre-industrial queen of battles, so decisive elsewhere, was curiously absent.

The Moroccans proved themselves impressively magnanimous. Empowered by the awesome scale of their victory, and the fortune to be made from ransoming captives, they behaved with chivalric restraint. In a bloody age so often marred by the horrendous cruelties unleashed by the sack of cities and the public torture of dissidents, it should be remembered that at the end of the Last Crusade no massacre of captives was ordered. Nor were the bodies of the dead defiled. No enemy soldiers were crucified or impaled, no heads dispatched in leather bags or jewelled caskets to horrify a foreign court. Instead, in the morning light, two Portuguese royal servants were instructed by the new Moroccan Sultan to search through the bodies of the dead and identify their king. Sebastian’s body had been stripped of its valuable armour but was otherwise undefiled. His corpse was washed and bathed in myrrh and sent back in honour to his cousin, Philip II, accompanied by the Spanish ambassador, and the captive ten-year-old son of the Duke of Braganza was released without ransom. This gesture so impressed Philip II that he sent the Moroccan court a gift by return: an emerald the size of the dead King’s heart and his body weight in sapphires, carried in solemn procession by forty Spanish lords.

During the daring cavalry attack that the Crusaders had launched right at the centre of the Moroccan army, Abdul Malik had used the last ounce of his strength to move forward and fight beside his bodyguard. Shortly after the enemy had been repulsed, he was seized by such a paroxysm of pain that he fainted. He recovered consciousness but briefly. Half an hour later he was taken from the world by an even more violent attack. His Jewish doctor continued to pretend to nurse him throughout the rest of the day, long enough for the Moroccan cavalry to begin their destruction of the Crusader square. Abdul Malik’s young brother, as commander of the cavalry that day, was directly responsible for the scale of the Moroccan victory and was able to ascend the throne in triumph. The thirty-year-old Sultan took the title of ‘al-Mansur bi Allah’, ‘Victorious by the Will of God’. There were no other claimants to the throne, for the former Sultan, Muhammad al-Mutawakkil, had also been found among the dead.1 It was reported that he had drowned at the ford, caught by a broken stirrup while trying to escape from the field of battle. This is usually accepted as fact, but may be no more than the customary denigration of a so-called ‘traitor’. He had certainly shown his martial qualities earlier in the day when he and his men had fought beside the Crusader cavalry. His body alone was signalled out for retribution. It was stuffed with straw and sent on a tour of his old allies among the cities and tribes of northern Morocco.

The garrison at Asilah and the Portuguese fleet anchored offshore could hear the distant noise of the Battle of the Three Kings, but they kept to their orders and held their position. As the news came in the next day with a trickle of survivors, a first wave of paralysis swept over Portugal. It seemed that all glory had been buried that day with their king. The survivors, though they may have behaved as bravely as any man, were tainted with a personal failure of feudal loyalty. They had not stood beside their king and defended him to the last. It would take ten days for a messenger to reach Lisbon. On 14 August the herald made his way to the Cistercian monastery of Alcobaca to break the news to sixty-four-year-old Cardinal Henry. The old regent was forced out of retirement and once again took up the reigns of power, this time as King Henry rather than as cardinal-regent. He was even prepared to relinquish his celibacy, and applied for a dispensation from the Pope to marry the thirteen-year-old daughter of the Duchess of Braganza.

That winter there was not a house, a cottage, a farm or a castle which did not have cause to join in the national grief. Portugal’s mood at that time has been compared to that of Scotland after the flower of the nation perished at Flodden Field in 1513. In a single day the nation’s proud nobility, its militant gentry, its brave young peasant volunteers, the entire court, army and administration, had perished. And with them the future lifeblood of the nation state. As Camões wrote in 1579, ‘All will see that so dear to me was my country that I was content to die not only in but with it.’ King Sebastian had never married, there was no direct heir and now only an ancient (and childless) cardinal sat slumped on the throne. Next in line for the throne, thrice cousin of the Avis through innumerable marriage alliances forged with the Habsburgs at every generation, was King Philip II of Spain. The old fears of being swamped by the Kingdom of Castile, which had first sparked Portugal in its crusading enterprise, were finally and inexorably coming true. Once news of the defeat had spread, it took but a second to realise that there was a second tragedy awaiting Portugal over and above the casualty figures of the Battle of the Three Kings. The country and its vast empire were fated to disappear into the vast conglomerate inheritance of the Habsburgs. There could be no doubt that Philip had the military power, money, determination and physical proximity to fulfil his legal right. He also had the moral satisfaction of recalling how he had counselled the young Sebastian against the invasion. He wrote to the city of Lisbon, ‘There is no man living in the world, which hath received so great of the loss of the king my nephew . . . because I lost a son, and a friend, whom I loved very tenderly.’

Seven days later the agent for Fuggers’ Bank in Lisbon sent a detailed report to his masters in Augsburg. For the commercial and financial implications of the Battle of the Three Kings threatened to topple the delicate balance of power within Europe. The King of Spain, lord of the vast silver deposits being unearthed by a slave army from the bowels of the mountain of Potosi in Peru, was fated to become the King of Pepper and the King of Sugar too.

There would be a half-hearted attempt to create a Portuguese candidate for the throne, though the cause of the claimant, Dom Antonio, would be greatly hindered by the transparent self-interest of his most ardent supporters, the dowager-queen of France, Catherine de Medici, and Elizabeth of England. Old King Henry, though he dithered about the fate of his nation, still hoped to sire an Avis child heir and was not prepared to compromise his perception of natural justice. He pronounced Dom Antonio a bastard, and in January 1580 solemnly declared in favour of the legal heir, King Philip II. Before the end of the month Henry was dead and Portugal, her empire, her wealth, provinces, fleet and fortified cities had passed into the hands of Philip II King of Castile and Aragon.