(Al-Qaṣr Al-Kabīr)

In 1557, after presiding for thirty years over his rich, prosperous and ever more diverse empire, King John III joined his ancestors in Batalha Abbey. He had outlived his own son and was succeeded to the throne by his three-year-old grandson, Dom Sebastian. The child’s mother had felt obliged to return home to Spain in order to care for her dying father, Emperor Charles V. So she left her infant son in the charge of her aunt Catherine, who was also the boy-king’s grandmother and a sister of Charles V. She did her best to preside over the royal council of Portugal as the dowager-queen-regent. She did this for five conscientious years before her place at the head of the council chamber was taken by another elderly relative of the boy-king. In 1562 the new regent, Cardinal Henry, placed his great-nephew in the care of a pair of Portuguese Jesuits, the brothers Luis and Martini Goncalves da Câmara. This switch in tutors and guardians coincided with exciting news from Morocco, where one of the few remaining Portuguese outposts, the fortress of Mazagan, had been besieged by the Moroccan army. To the pride and pleasure of the boy-king, his garrison of two thousand six hundred men had held off the entire Moroccan army. Or so it seemed. From a Moroccan perspective, the 1562 attack on Mazagan served quite a different purpose. The attack was organised by the Sharifian Sultan of Morocco, who had failed once again to recapture Tlemcen from the Turks some two years before. Despite this attack, the Turks had proved reasonable and Sultan Abdullah al-Ghalib was able to patch together a truce. The 1562 siege of Mazagan helped restore his standing as a Muslim leader who was seen to be attacking enemy Crusaders rather than fellow believers. It also seems to have been mere cover for the Sultan’s real ambitions. The siege was combined with a determined march through the northern mountains of Morocco which allowed the conquest of the Idrisid Emirate of Chechaouen, an old ally of the previous Wattasid dynasty. This explains why during the siege there were just twenty-four Moroccan cannon available to fire upon the strong fortress walls of Mazagan. None of this realpolitik interested the boy-king of Portugal, who remained thrilled by the heroism of his soldiers and their commander, Rodrigo de Sousa de Carvalho. In due course De Carvalho was promoted to become the next governor of Tangier, from where his young master repeatedly urged him to launch an aggressive forward policy.

Six years later the fifteen-year-old Sebastian formally came of age. The grave, good-looking prince became a taciturn, athletic and dignified young king. His favourite possession was a suit of armour that had been manufactured for him by the master-smiths of Augsburg, the tempered steel chased with elegant gilt symbolism. When King Sebastian exercised in this armour, the four virtues on his arms moved, while the proud achievements of the Portuguese crown that were etched into the breast and backplate – Power, Victory, Peace and Navigation – remained still. It was noticed that the dark-haired, swarthy, sensual bloodline of the Avis was absent from Sebastian’s make-up. The slender young man, with his pale skin, blue eyes and fair hair, seemed to be a throwback to his English and Trastamaran ancestors. The combination of Jesuit tutors and a complete lack of parental relationship burnished his nature with a clear absolutism. Sebastian possessed the bright stare of a fanatic, determined to return Portugal to the pure zeal of its crusading inheritance. He was said to be equally inspired by the victory over the Turks at Lepanto and the massacre of Protestants in France on St Bartholomew’s Day in 1572. At first he imagined that he might follow in the footsteps of Alexander and launch an attack on the Muslim heartlands through India. Indeed the Portuguese garrison in Goa had to defend itself against a very determined siege made in the very same year as Lepanto. However, in due course his attention shifted back to Morocco, the traditional enemy of a Portuguese Crusader.

In 1570 a well-travelled warrior who had served in Portugal’s vast empire returned home. He was a cousin of Vasco da Gama. His own father had been drowned in the Indian Ocean and he himself had lost an eye as a young man while serving in the defence of Ceuta. He went on to serve the crown in Macao, Malacca and the Moluccas. When at last he returned home to Lisbon, he found that his old city, his beloved country and countrymen, seemed to have been transformed into something unfamiliar, mercenary and unwelcome. Throughout his long, adventurous service and worldwide travels this Portuguese soldier had been composing an ode to his motherland that was inspired by Virgil’s Aeneid. The work had been destroyed at least twice, once in Mozambique, another time in a shipwreck off the River Mekong. However, the destruction of these earlier drafts, married to the disillusionment of home-coming, made the final work much tighter and stronger. The epic poem was dedicated to the young King Sebastian, who read Camões’s masterpiece, The Lusiads, while it was in manuscript. The defining national epic of Portugal concludes with a call to return the nation to its days of martial glory and to cleanse it of the corruption and confusion of its great wealth. Camões was rewarded for his work. His ode was printed at royal expense and he was given a small annual pension, which in those pre-copyright days was the best a writer could hope for.

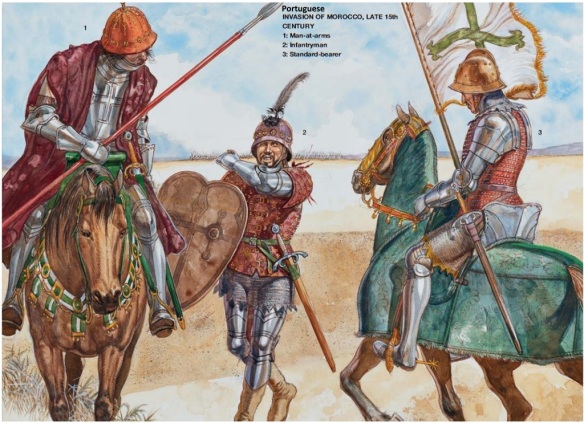

In 1574 Sebastian was at last able to test himself, and his years of martial training, by leading an expedition into Morocco. Like his ancestors before him he crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and landed at Ceuta. That summer the gates of this fortress opened and the young king led a column of twelve hundred armed knights through the Anjera hills of northern Morocco. A cavalry battle was fought outside the walls of Tangier, where Sebastian proved himself a skilled and determined young commander. Those long years of obsessive boyhood training had not been in vain.

That winter the King was back in Lisbon. He started plotting with the arch-schemers and spy-masters of the Queen of England’s court. Inspired by the assassination of Sharif Muhammad by Ottoman agents which had taken place some twenty years before, King Sebastian proposed establishing his own fifth column of secret agents within the Moroccan army. To do this he suggested that a handful of English corsair captains, men of the piratical stamp of Francis Drake, be employed to enslave a boatload of loyal Portuguese soldiers and sell them as military slaves to the Moroccan Sultan. It was a daring if slightly hare-brained scheme and was soon dropped. For in 1576 the young Sultan of Morocco was deposed by his uncle after just two years on the throne. The former Sultan fled to the fortress of Ceuta as the Portuguese were his only possible allies. It had become apparent that his uncle Abdul Malik’s palace coup had the advance approval of both the Ottoman Empire and the King of Spain.

Sultan Abdul Malik had assembled some formidable backers for the coup d’état that finally put him on the throne. Born into the holy bloodline of the Sharifian dynasty of southern Morocco, Abdul Malik was one of five sons who served in the army led by their father, Sharif Muhammad esh-Sheikh. After the assassination of the Sharif by Ottoman agents in 1557, the young prince had been forced to escape Morocco. For his elder half-brother, Sultan Abdullah al-Ghalib, had begun to purge the country of all possible dynastic rivals. The fifteen-year-old Abdul Malik, in the company of his younger brother and their capable mother, Sahaba Errahmania, sought refuge in Algeria. They lived – closely watched by their hosts – first in the old medieval city of Tlemcen before moving to Algiers on the coast, the new booming city enriched by the booty of the corsair captains. Years later they were given permission to travel to Istanbul, where they petitioned the Ottoman court for assistance in taking the Moroccan throne. These petitions fell on deaf ears but the brothers made some good and unusual friends during their years of exile in Algiers and Istanbul: a Christian barber-surgeon, a Spanish priest working among the slaves and a French sea captain. It may have been the example of these free-spirited friends that encouraged the two brothers to take their fate in their own hands. They volunteered to fight in the fleet, and though Lepanto was a catastrophe for the Ottoman navy, the two Moroccan princes survived. Their fighting spirit brought them to the attention of the Ottoman court. When they also volunteered to take part in Admiral Uluj Ali’s campaign to recapture Tunis and Goletta in 1574 they acquired an influential patron in the person of the corsair admiral of Algiers, turned commander-in-chief of the Ottoman navy. Two years later ministers at the Ottoman court, where Murat III had replaced his father Selim II on the throne, agreed to provide the two exiled princes with men, money and munitions. In exchange Abdul Malik promised to reward his backers with a payment of five hundred thousand ounces of gold and to lease the Moroccan port of Larache to the Ottoman fleet. The acquisition of an Atlantic port would allow the Turks to out-flank Spain in any future maritime conflict and would give the corsair captains of Algiers a chance to prey on the silver bullion being shipped into Seville from Peru.

Abdul Malik’s Ottoman-backed invasion of Morocco in 1576 proved to be a most efficient coup. His half-brother Sultan Abdullah al-Ghalib had died and his son, Muhammad al-Mutawakkil, had but a loose grip on the throne. Abdul Malik was well supported by his network of friends and confidential agents, many of whom dated back to his days as a refugee in Istanbul. The troops loaned by the Pasha of Algiers (then under the command of Ramadan Bey, a renegade from Venice) were handsomely rewarded and sent back home before they made themselves unpopular. The question of the lease of Larache was politely shelved, for Abdul Malik had no desire to antagonise Spain or to allow Morocco to become an Ottoman protectorate.

But it was this coup of 1576 that gave King Sebastian both a pretext and a local ally for his invasion of Morocco. He could invade Morocco under the cover of placing Muhammad al-Mutawakkil back on the throne. In 1577 he crossed the frontier to have a meeting with his cousin, King Philip II of Spain, at the monastery of Guadalupe. Philip was intrigued to meet a man even more austere, passionate, zealous, isolated and friendless than himself. It seems to have brought out the best in him and he tried to counsel his young cousin: to be cautious and not to risk his life until the succession of Portugal had been secured by marriage and the birth of an heir. It was good advice but Sebastian, too young to have joined the Holy League and fought under Don John of Austria at Lepanto, could not be dissuaded. Philip agreed to assist with the loan of an experienced Spanish regiment, but only if a rational timetable was adopted and an achievable tactical target were set, such as the seizure of the port of Larache. Assured of the support of Spain, Sebastian sent his financial agents on a shopping tour of Europe to recruit German soldiers and acquire Italian and Flemish munitions. At the same time he licensed four proprietary colonels to tour the inland provinces of Portugal recruiting four regiments of native infantry. The Portuguese peasants had little understanding of the nature of modern warfare but it was a good time to hire experienced mercenaries from the Duchy of Burgundy. Both the Catholic and Protestant factions within the Duchy (the Netherlands and Belgium had not yet been created from the wreckage of the Dutch Revolt) were sick of their ‘own’ soldiers. The Prince of Orange was disgusted by the excesses of the Protestant soldiery of such mercenary commanders as Duke Adolf of Holstein, just as Catholic loyalists had been appalled by the spectacular own goal of the sack of the royalist city of Antwerp – the so-called ‘Spanish Fury’ – by the very men who were supposed to be defending them.

Munitions were another matter. The Italian powers were enthusiastic in principle about a crusade but very exact on matters of price. The Duke of Tuscany would be honoured to release a loan of two hundred thousand gold ducats so that King Sebastian could acquire arms from Ferrara, Milan and Mantua, but only after Portuguese pepper had been landed at the docks of Livorno. So Sebastian’s agents went to talk to the Jews of Antwerp, who were less keen on listening to the broad principles of a crusade but were much more flexible on matters of schedule. They released enough money to his agents for them to buy three thousand muskets and four thousand arquebuses on the open market. In exchange they got a paper promising the delivery of ninety-two thousand quintals of pepper in three years’ time.

The Englishman Sir Thomas Stukeley (or Stucley) came in as an after-thought to King Sebastian’s crusade. Sir Thomas had a varied career, by turns a pirate, spy, counterfeiter, secret agent and diplomat. Or, as Camden described him, he was ‘a ruffian, a spendthrift and a notable vapouriser’. He had, however, been one of the very few Englishmen to fight in the Holy League under Don John at Lepanto. He was also rumoured to be the natural son of King Henry VIII, which helped him win the financial support of the papacy. When he sailed into Lisbon harbour in the spring of 1578 he was supposedly leading a scheme to land a Catholic army in Ireland and march to the aid of the Irish leader Shane O’Neill, who was struggling against the troops of Protestant England. To that end the Pope had just made Sir Thomas the Marquis of Leinster and lent him enough money to buy a ship and the loyalty of a regiment of six hundred mercenaries.

When he called into Lisbon (whether by chance or privy arrangement) Stukeley at once offered his service to King Sebastian and scuttled his ship as too unseaworthy to cross the Bay of Biscay. The Pope was appalled, Queen Elizabeth I relieved, although the subtle monarch of the English had already decided to play it safe and support both sides in this conflict. England and Morocco had a lot in common in the last years of the sixteenth century, for both countries feared an invasion by a Catholic army and needed to acquire armaments. It was not considered expedient by either the Christian Queen or the Muslim Sultan to make too much noise about their trade, but Moroccan saltpetre was liberally traded for English munitions. The one attempt to create indigenous English gunpowder had been an interesting experiment. All the earth-closets of London had been commanded to deposit their night-soil in a low pyramid covering some five acres on the edge of the city. This was then drenched with various chemicals, in the expectation that saltpetre crystals would emerge like mushrooms to be plucked from the heaving morass of rotting, rain-drenched excrement. The experiment was not repeated. Instead such well-connected arms dealers as Edmund Hogan continued their private missions to the Sharifian court. Hogan led a curious double life, publicly upbraided by the Queen when in earshot of a Portuguese or Spanish ambassador, but privately cherished in the meetings of her inner counsellors.

So, in the immediate pre-war months, we hear that captain Francis Drake had dropped in at Mogador and sent one of his crew, John Fry, to take a message to the Sultan. The Queen also arranged that an English grain ship would call into Lisbon. This was full of mercenary types who would enter the King of Portugal’s service once they landed and included two trusted agents embedded among their number.