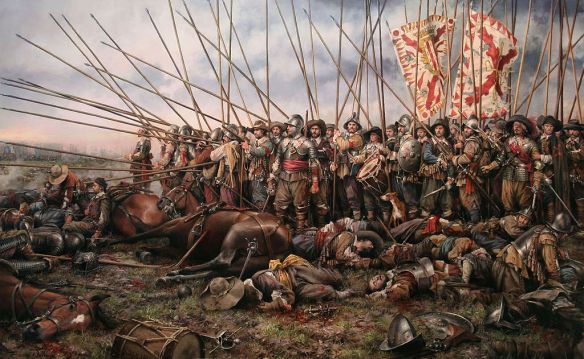

Rocroi, the last tercio, by Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau

In contrast with his simpler strategy of 1642, when he had fought with united forces, (and in accordance to his penchant for secrecy and drama) Melo decided to split his troops into six army corps whose commanding officers did not learn the true objective of the campaign until the very last minute. The first detachment, led by don Andrea Cantelmo would closely watch the Dutch in the northern front, the second led by the Count of Fuensaldaña would defend the province of Artois, the third composed of six thousand soldiers marching from Luxembourg under Infantry General Jean de Beck he assigned to the siege of Chateau-Regnault, about 12 kilometers from Rocroi on the river Meuse, meant to serve as a conduit for troops and materiel; the fourth under the Count of Bucquoy was based in Hainault; Melo kept the fifth under his command and ordered the so-called “Army of Alsace” under Count Ernest of Issembourg to feign a move on Landrecies and then quickly turn southeast to invest the town of Rocroi. Issembourg promptly obeyed on the 12th of May and after joining with Bucquoy’s Walloons Melo took control of the operation on the 13th. Meanwhile in France, the young Louis de Bourbon, Duke of Enghien and later Prince de Condé, seeing an opportunity to inaugurate his generalship with distinction, began hurriedly to prepare a relief expedition. Like Melo, he was willing to gamble on one massive thrust but unlike his counterpart he decided to unite most of his forces to fight at maximum strength. In order to do this he stripped French border garrisons of personnel and thus significantly raised the stakes on the outcome of the battle. Had the tercios won they might have found their way to Paris open.

Rocroi was an attractive target. Regarded by the Spaniards as “the gate of the Champagne” and described by Enghien as “one of the best fortresses in France” it could serve as an excellent plaza de armas or rallying point for a drive towards Paris such as the Cardinal-Infante had conducted seven years earlier. Its fortifications were reportedly in some disrepair, the garrison was known to be manned by roughly four hundred soldiers, and its Governor, Monsieur de Geoffreville, was ill and unable to lead the defense. Furthermore, Rocroi’s location presented several clear tactical advantages. The town stands in the middle of a plain several kilometers wide, ideal for the encampment of a besieging army (and of course, for a battle). The surrounding woods and marshes, more abundant then than today, made access difficult for a relief force, and the only direct path into the open plain before the city gates was easy to guard. Thus it seemed, at least at first sight, that all the political, tactical and topographical premises were in Melo’s favor and against Enghien. But, unbeknownst to the Captain General, the French had already intercepted some of his communications, the surprise factor was gone and, above all, the Army of Flanders had serious problems of its own.

“When have so many errors ever been seen as on this occasion?” asked Albuquerque after the battle. In his haste to go out early on campaign Melo had committed some major logistical blunders. The spring of 1643 had been unusually cold; frosts were still common in May and in the Ardennes the ground may have been frozen in many places; these conditions had prevented or slowed the growth of forage grass and hay and cavalry horses were ill-fed, weak and unprepared to engage in battle. Normally the cavalry did not ride out on campaign until there was grass enough to feed it, and there was difficulty in obtaining food supplies during the siege. Furthermore, money sent from Madrid had not been enough to provide new horses and saddles for the cavalry or even enough bread for the tercios who were thus forced to advertise their presence by raiding and ravaging the surrounding countryside. Although there were not enough carts to carry provisions there was, as usual, a lavish baggage train with the officers’ personal belongings, to which Melo seems to have added some fanciful touches such as a private orchestra. This baggage train, which was to play a major role in the outcome of the battle, was so precious to this luster- hungry Captain General that he rejected all advice to leave it behind. (In contrast, Enghien left most of his miles away).

Despite their large baggage train, the tercios did not carry enough heavy artillery to force the surrender of Rocroi before the arrival of the French relief army and the town was found to be much better fortified than had been reported, the first of a series of crucial failures of military intelligence. Consequently the French garrison fired upon Melo’s troops, delaying their advance and inflicting sobering casualties, especially among the army’s Italian tercios who shouldered the brunt of the early assaults. Shovels, spades, cudgels and other siege instruments that would have allowed the tercios to fortify their position and avoid battle, were insufficient (perhaps because many had been shipped to Spain earlier) and probably the hard semi-frozen ground made digging difficult. In addition, erroneous military intelligence had led Melo to conclude that the French would not be able to organize a relief effort on time. Given the topographical conditions described above, had the Spanish army been able to strengthen its encampment with the defensive works that besieging forces generally used in this period (and which had, ironically, been pioneered by Spanish commanders in the early sixteenth century), it would have been in an unassailable position, Enghien’s arrival, had he mounted an unlikely relief effort under such conditions, would have been for nought and Rocroi would have almost certainly fallen as ‘sHertogenbosch had fallen to the Dutch fifteen years earlier. In fact French and the Spanish accounts concur that only one more day of siege would have been necessary for the capitulation of the town. But the Army of Flanders would not get that extra day. The lack of proper siege equipment precluded the effective encirclement of Rocroi as well as the construction of an outer line to protect the besiegers from a relief force, and, as the French realized, left enough room to squeeze a second army into the surrounding plain. Enghien rapidly took advantage of this oversight and introduced reinforcements into Rocroi on the night of the 17th which guaranteed that the siege would go on for a few more days, and gave him time to approach.

At this point Melo blundered again. Although he must have been aware that given their unfortified position the tercios would have no option but to fight if Enghien came near, he did nothing to prevent the French from filing through a series of narrow paths through the woods and marshes into the plain of Rocroi. As contemporary observers, French, Italian and Spanish, agreed, this was one of the most delicate land operations in seventeenth-century warfare, and it would have been relatively easy or at least feasible to ambush the French as they could not have kept in formation while approaching. Melo could have at least held them off and gained time for Beck to arrive with six thousand reinforcements who would have given the Army of Flanders a significant numerical advantage. However, the Captain General took no steps of any sort to challenge Enghien at this favorable moment and permitted him to come through unhindered, either because he knew very little about French troop movements or else due to the rivalry between Albuquerque, who may have offered to set up an ambush, and Fontaine who refused to allow it. Then, instead of charging the arriving soldiers before they could fall into line, he allowed them to arrange themselves in battle formation. (The French skirmishers Jean de Gassion had sent forward may have provided the necessary cover for the second wave of infantry, as one contemporary narrative suggests). Even at this point, Melo might have taken cover behind a stretch of marshland that laid behind him to his right, between his forces and Rocroi. There he would have been in a strong position to wait for Beck, force the surrender of the town and then fight the battle but Melo again did nothing. His inactivity was partly the result of a command style and ethos based on aristocratic values expressed through grand gestures and poses, that did not admit tactical retreat as an honorable option, for according to Melo, “the courage of a General of the King of Spain could not allow [him] to show fear by hiding behind a marsh, but [forced him] to go out in the open to wait for the enemy there.” Clearly the old tactical principles of the Duke and School of Alba, built upon ambush, skirmish and the avoidance of battle unless in overwhelming numerical and positional superiority had already been abandoned in favor of a bolder, riskier policy, more in tune with a new type of high command officer and a more desperate strategic situation. Perhaps too Melo had an inordinate confidence in his generalship and a more justified trust in the quality and reputation of his troops, undefeated in a previously chosen battlefield position for more than a century, (although, as some had already noticed, the time when the enemies of Spain had systematically avoided direct confrontations with her celebrated infantry was already drawing to a close). Other likely factors include the apparent inability of the tercios, in their deep formations, to move quickly enough to challenge the French or to go very far in any direction as well as certain political considerations. Possibly aware of Louis XIII’s death on the 14th, Melo may have also been seeking a major victory that would drive the French to the peace table, reaffirm his position as Captain General after the fall from favor of his patron Olivares and might even help the Count-Duke return to power (an event widely expected in Madrid those days). If it was a clash that Melo wanted, he would get his wish. As French riders, musketeers and pikemen poured into the plain and quickly took up combat positions other tactical options vanished. Soon the sun began to set, making any further moves extremely chancy. The tercios were caught between the woods and bastions of Rocroi and the pikes and guns of Enghien. Battle was now the only way out.