Flying by moonlight, No. 161 Squadron, RAF, slipped into occupied France to deliver precious cargoes of secret agents.

The need to supply the various resistance units around Europe, particularly in France and Yugoslavia, with weapons, radios and equipment led to the formation of a specialised RAF unit known as No. 1419 (Special Duties) Flight. This small unit utilised the Westland Lysander and the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, aircraft that Bomber Command were happy to part with as they were considered obsolete.

This unit would then go on to form the nucleus of a much larger operation as SOE came in to prominence, forming No. 138 and No. 161 Squadrons. The former would use large bomber type aircraft to drop agents, known as ‘Joes’, and stores into occupied territory whilst the latter would specialise in the ferrying of agents in and out of occupied territory. The formation of these units went against the wishes of the head of Bomber Command, Arthur Harris, who thought that every available aircraft and aircrew should be involved in the night bombing campaign of Germany’s industry. The importance of SOE and the supply of resistance fighters around occupied Europe made his wishes redundant and were overruled.

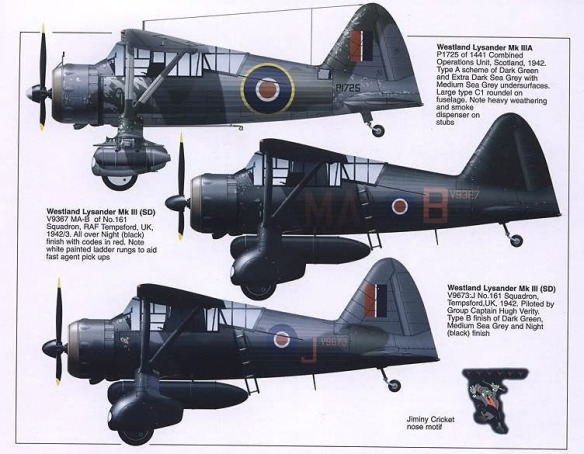

This did however mean that the supply of aircraft to the units came in a trickle. The first aircraft was the Lysander, initially used as an Army cooperation aircraft, spotting for artillery. The aircraft had one major advantage. It had an incredibly short take off and landing capability and with the addition of a ladder attached to the rear cockpit this was used as a fantastic ‘taxi’ for agents without parachute training to enter or leave occupied territory. In the months leading up to D-Day 101 agents were inserted whilst 128 were recovered by the Lysander flights. The RAF also used the American designed Lockheed Hudson, a twin-engined aircraft with a much greater range than that of the Lysander but with a landing and take off run twice that of the smaller aircraft. However, this was capable of carrying a far greater number of agents, ten as opposed to a maximum of three, and was used when suitable landing sites could be found. The Whitley, was a two-engined bomber that was quickly replaced by the much larger Handley Page Halifax. This aircraft was a four-engined bomber and capable of carrying a vast amount of stores that could be parachuted down in containers, it also had a fantastic range, managing to reach as far east as Poland, whilst flying from bases in southern Italy.

The squadrons were based mostly in southern England, for ease of flying their missions to France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy, their main bases being at RAF Tempsford and Newmarket. However, if they were required to fly to Norway Scottish airbases were used as were North African bases or Italian bases used when flying to Eastern Europe.

The USAAF also introduced specialised squadrons of aircraft for the delivery of stores to the resistance fighters of Europe. Their first operation, flying heavily modified Consolidated B-24 bombers, was Operation Carpetbagger which began in early January 1944 and would continue until September of that year. From then on the units would be known as the ‘Carpetbaggers’.

Supply missions would mostly be carried out on nights where there was a full moon to aid in navigation. The aircraft would fly alone and at the relatively low level of 500–1,000 feet. This would also help in navigation as river, rail and road networks could be clearly seen from that height. On the ground the resistance fighters awaiting the arrival of a drop would mark the drop zone with torches or fires or later on the introduction of Eureka and Rebecca radio direction finding sets, these were rare and often failed. In total tens of thousands of weapons and supplies were dropped by these units throughout the war, without these missions many of the resistance units would have found it impossible to take the fight to the enemy.

No. 161 Squadron

No. 161 Squadron, brought into the fray in February 1942, was formed at Newmarket in Suffolk around a nucleus supplied by elements of the disbanded King’s Flight and of No. 138 Squadron. Wing Commander E H. ‘Mouse’ Fielden, who previously was captain of the King’s Flight, became No 161 Squadron’s first commanding officer, and the new squadron’s aircraft, an assortment of Lysanders and bombers, included one Lockheed Hudson from the disbanded unit.

On the night of 27/28 February 1942, Flight Lieutenant A.M. `Sticky’ Murphy, piloting a Lysander carried out the squadron’s frost pick up operation Everything went according to plan, unlike an earlier sortie flown by Murphy when he was serving with No. 138 Squadron. On that occasion he had landed m a field in Belgium and come under fire from German troops lying in ambush. Although wounded m the neck and losing a lot of blood, he, nonetheless, succeeded in flying his Lysander back to Tangmere. In March 1942, Murphy was promoted to squadron leader and took command of ‘A’ Flight. His next mission to France was rather unusual, as it was the only occasion on which an Avro Anson borrowed from a training unit was used for a pick up operation. It was needed because four passengers were to be collected from a field near Issoudun, and the Lysander’s normal passenger load was only two. Although visibility was poor, which made visual navigation difficult, Murphy eventually reached the landing zone.

‘Landing completed without trouble and the four passengers embarked very rapidly,’ he later reported. One of these passengers was Squadron Leader J. Whippy’ Nesbitt Dufort, a Lysander Special Duty pilot of No. 138 Squadron who had been forced by heavy ice to crash land in France during a pick up operation on 28 January. After a month in hiding with the resistance, he was relieved to be rescued and breezily reported of his homeward flight: ‘The skill of the pilot and the navigator proved in this case to be exceptional, as we were only lost the majority of the way home.’

In March 1942, No. 161 Squadron moved from Newmarket (where it had operated from the famous race course) to Graveley in Huntingdonshire, before settling at Tempsford, Bedfordshire, in April. This airfield, which it shared with No. 138 Squadron, then became the centre of RAF Special Duty operations: ‘It was not much of a station,’ thought Squadron Leader Hugh Verity. ‘It was a rush job quickly built in wartime, like hundreds of others. Officers’ mess, station headquarters, squadron offices and all the rest were temporary huts,’ A farmhouse on the site, Gibraltar Farm, was used by the SOE to prepare agents for parachute drops and to store supply containers, while the Lysander missions were generally flown from the forward base at RAF Tangmere in Sussex, where No. 161 Squadron used a cottage opposite the main gates as their crew room.

The Lysanders used for pick up operations were stripped of all armament and carved a 150 gallon auxiliary fuel tank beneath the fuselage to order to increase endurance to eight hours. A ladder was fitted to provide easy access to the rear cockpit, which usually accommodated two persons but could take three or even four adults cramped together. Since the pilot had to navigate himself over enemy territory, usually relying solely on map reading, it was essential that operations took place within the full moon periods Wing Commander Lewis Hodges, commanding officer of No. 161 Squadron during 1943/44, who was destined to retire from the RAF as Air Chief Marshal Sir Lewis Hodges, recalled:

‘Our lives were governed by the phases of the moon. We needed moonlight to map read by; we needed moonlight to find our way to the dropping zones for parachuting and to the small fields that served as landing grounds; and we needed moonlight to be able to see the ground clearly enough to make a safe landing.’

The resistance ‘reception committees’ were warned by a cryptic radio message over the BBC’s French service that a pick up or parachute drop was scheduled for them that night. The pre-selected landing fields had to have an approach unobstructed by tall trees or other obstacles, and were expected to provide a firm and level surface of at least 600yds in length. However, in practice many fields fell far short of these requirements, sometimes with serious consequences. The reception committee was responsible for laying out a rudimentary flare path, consisting of three lamps, to mark a landing run into the direction of the wind. Once the Lysander pilot had found the field, an identifying code letter was flashed to him in morse to signal that all was well. The Lysander would come in to land and turn into the wind to be ready for take-off, before disembarking its agents, (invariably known as ‘Does’ or ‘Janes’, according to sex) and picking up those to be carried out. The time on the ground was naturally kept to a minimum, and a smooth pick up could be accomplished within three minutes.

Parachute dropping operations, which were far more frequent than landings, employed broadly similar procedures. The dropping zone was marked by a pattern of lights, and the reception committee again identified itself to the Special Duty pilot by a code letter. The supply containers, sometimes accompanied by agents, were then dropped from an altitude which was sufficiently high to ensure that the parachutes deployed properly, but not so high that the containers were scattered over a wide area This kind of operation called for precise flying skills if the loads were to be delivered within the designated dropping zone. By 1944 the job of supply dropping had been made easier by the introduction of the Eureka/Rebecca navigation beacon system, which enabled the aircraft to home onto the dropping zone.

The pilot and reception committee were also able to communicate using the `S phone’. In theory, all the Special Duty pilots were proficient in French and at least one member of each reception committee was to have received training in basic flying control techniques, but since, in practise, these requirements were often relaxed, the S phone was not always particularly useful.

Despite the operational dangers it faced: 161 Squadron’s casualties were not especially heavy, a fact attributable largely to the high standards of navigation and airmanship achieved by its crew. Enemy action was an ever present threat, with the Special Duty aircraft being vulnerable to German flak and nightfighters when in the air, and to ambush when landing in France. In the event, two Lysanders were lost to German anti-aircraft fire, but the only ambush attempted by the enemy failed to prevent Flight Lieutenant ‘Sticky’ Murphy from returning to base. Bad weather, especially when it involved poor visibility and ice, was another hazard. On one disastrous night, 16/17 December 1943, two Lysanders were lost and their pilots killed when they crashed in fog while trying to land at the end of a mission. Again, aircraft were frequently damaged or bogged down after landing on unsuitable fields. For example, on 16/17 April 1943, Flight Lieutenant John Bridger’s Lysander hit a high tension cable when attempting to land on a field south of Clermont Ferrand. The blinding flash temporarily destroyed his night vision, but he kept control of the aircraft and landed to disembark his passengers. One of the mainwheel tyres had burst and Bridger decided to puncture the other with a shot from his revolver in order to make his take off easier. Fortunately the wheel rims did not dig into the ground and he was able to return safely to base.

The landing strips were sometimes found to be too boggy to take the weight of an aircraft, and on several occasions pilots were forced to abandon their trapped aircraft in France. One of the less serious of these incidents took place on the night of 24/25 February 1943 and involved a twin engined Lockheed Hudson. Its pilot was Wing Commander P.C. Pickard, who had relieved Fielden as commanding officer of No. 161 Squadron on 1 October 1942, when the latter was promoted to Group Captain and given command of RAF Tempsford. Pickard was probably the best known bomber pilot in the RAF at that time, thanks to his role as the captain of the Wellington ‘F for-Freddie’ in the documentary film ‘Target for Tonight’ he was subsequently to be killed in action in February 1944 when leading the famous Mosquito raid on Amiens prison. Pickard had carried out the first pick up sortie flown by a Hudson on the night of 13/14 February and this had gone according to plan. However, on the more eventful mission 11 nights later, his aircraft had become stuck in a patch of muddy ground and, as one squadron member recalled, ‘his crew were armed to the teeth with revolvers, Sten guns and so on, but not so much as a teaspoon to dig themselves out.’ Eventually they succeeded in freeing the aircraft hindered rather than helped by an excited crowd of French villagers only to see the aircraft become bogged down again, By the time that the Hudson had been freed a second time dawn was approaching, and the aircraft was fortunate to reach England unmolested by German fighters.

The experience of Flight Lieutenant Robin Hooper on 16/17 November 1943 was even more nerve racking. His outward flight was uneventful and he recalled:

‘After two unsuccessful attempts I got down off a very tight low circuit (even for a Lizzie!), dropping in rather fast and rather late through the mist. I soon realised that the ground was very soft indeed . . .At first, when I braked the wheels just locked and slid; but very soon it was a question of using quite a lot of throttle to keep moving at all and it seemed best to keep moving at all costs. Turning was all but impossible since the wheels dug into deep grooves. Finally we managed to turn 90° to port and there stuck. The aircraft was immoveable even with +6 boost, so I told the passengers to get out and got down myself to inspect. We were bogged to spat level; the ground appeared to be wet, soggy water meadow. The reception committee came running up: I organised them to push and we attempted some more +6 boost without the slightest effect, except perhaps to settle the wheels a little more firmly in their ruts…

‘At this point someone suggested getting some bullocks from the nearest farm; after a certain amount of fuss this was agreed to and a small, well-armed party set off to collect bullocks, spades and some planks or brushwood . . . The rest of us continued to dig trenches in front of the wheels with the idea of making a kind of inclined plane up which they could be pulled. About 20 minutes later an odd procession loomed out of the mist; two very large bullocks trailing clanking chains, the farmer, his wife, his two daughters and the three chaps from the reception committee. The farmer shook me warmly by the hand and asked me when the British were going to land in France, and got to work.’

Despite the efforts of this team, later augmented by a further two bullocks, the Lysander remained firmly stuck. Flight Lieutenant Hooper decided to burn the aircraft and go into hiding with the resistance. He was picked up by Wing Commander Hodges a month later.

The liberation of France greatly reduced the calls on the Special Duty squadrons’ services, although drops of supplies and agents continued over other areas under enemy control. No. 161 Squadron’s last pick up operation was flown on 5/6 September 1944, by which time over 200 such missions had been successfully accomplished. The squadron’s contribution to the Allied war effort was greater than that figure suggests. In all some 6700 agents had been flown into Occupied Europe, of which not many more than 400 had been carried during pick up operations. Yet the latter flights had extracted more than 600 persons out of enemy territory and it was this service which was so uniquely valuable to the Allied resistance and intelligence networks. Moreover, No. 161 Squadron had made a significant contribution to the dropping of supplies to resistance forces, which in all received some 42,800 tons of materials supplied by air.

For the crest of its official badge, No. 161 Squadron adopted the motif of an open fetterlock. Its motto is ‘Liberate’. Neither is an overstatement of the vital role played by the squadron in releasing Europe from the yoke of Nazi occupation.