After the invasion of Norway the Germans took control of all aspects of Norwegian production, with one major coup being the capture of the hydroelectric plant at Vermork next to the Rjukan waterfall. This plant specialised in separating hydrogen molecules in water in order to produce ammonia, which could then be used in the production of fertilisers, a by-product of which was heavy water, which in turn could be used by the Nazi war machine in its Plutonium production. With a nuclear weapon the Axis powers would be unstoppable so a plan was put into action to knock out the plant and destroy all the heavy water that had already been produced.

Luckily for the Allies an engineer from the plant, Einar Skinnarland, was on a month-long sabbatical from the plant and managed to escape to Britain. Here he gave valuable information to the SOE who decided to return Skinnarland to Norway before his break was over so as not to arouse suspicion and to help lead a sabotage attack against the plant. RAF bombing of the plant was thought to be too costly as the weather was unpredictable in the mountainous region as well as the plant being a formidable construction, many many bombs would have to be expended before any tangible results were to be seen.

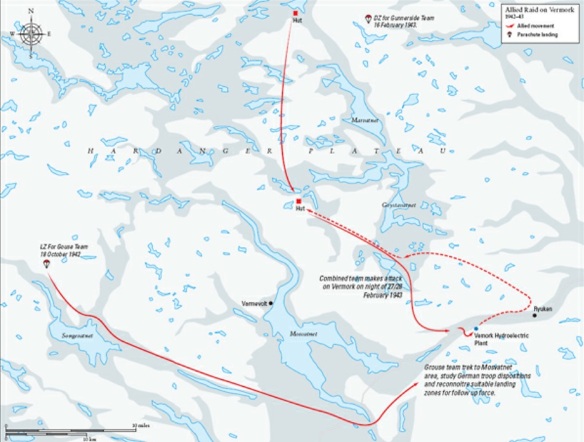

With Skinnarland successfully dropped back into Telemark, it was decided to send an advance party made up of four Norwegians familiar with the region. This would be known as Operation Grouse. These men were; Jens-Anton Poulsson, the leader, Knut Haugland, Claus Helberg and Arne Kjelstrup. They had undergone intensive training in the wilds of Scotland courtesy of the Commandos, learning invaluable skills such as sabotage, unarmed combat and extreme weather survival. After several attempts, which were aborted due to inclement weather the team was finally dropped on the Hardanger Plateau on 18 October 1942. They landed well west of any German garrison and it took them several days of trekking and cross country skiing to make the rendezvous at Mosvatn, where they met with Skinnarland’s brother. They immediately set about reconnoitering the area for a suitable landing zone for the gliders that would bring in the Commando assault team. This was found and reported back to London via radio. The men also sent back information gleaned by Skinnarland and his brother that the Germans had placed around twenty-four low grade troops to guard the dam and plant area, but with reinforcements within easy reach to repel any attack. The plant itself was perfectly protected, being in a steep valley with the approaches mined and guarded by machine guns.

With all the details assessed it was decided by Combined Operations to send in thirty-four sappers drawn from the Royal Engineers that were attached to the 1st Parachute Division, known as Operation Freshman. These men would be towed by Halifax bombers in two Horsa gliders, they would then land on a area 3 miles from the plant and rarely patrolled by the Germans. The men would then be escorted by the men of the Grouse Team to attack and destroy the plant and all heavy water.

On 19 November 1942 the operation was launched, even though the weather was far from perfect. The operation did not go to plan as the first combination of Halifax and Horsa could not locate the beacon set up by the Grouse team. Due to heavy ice the tow rope snapped, leaving the Horsa to crash land in southern Norway near Fyljesdal. Seventeen men were on board, eight being killed in the crash with many of the others badly injured. These men were found by locals but soon after the Germans located them and took them into custody. The other combination fared even worse, both the Halifax and the Horsa crashed, with no crew surviving aboard the Halifax. Aboard the Horsa seven men were killed and the rest injured. The men managed to make contact with the locals but again were discovered by the Germans and taken to a prisoner of war camp.

Unbeknownst to the Glider men Hitler had decreed the Commando Order a month previously, that all commandos should be shot immediately on capture. All the survivors of the two glider crashes were summarily executed. Along with this hideous war crime a map was found amongst the wreckage plotting Vermork as the target for the raid, the Germans increased security of the plant immediately.

With the failure of the operation the men of the Grouse team now had to retreat into their mountain hideaway, a small ski cabin high on the plateau north of the plant and exist on meagre rations, even resorting to eating lichen, until further on into the winter a reindeer was spotted and butchered.

On the evening of the 16 February 1943 a further six men were dropped on the plateau to supplement the Grouse team, known as Operation Gunnerside, these men were also Norwegian nationals who had been trained by SOE and the Commandos. Bringing with them much needed supplies and sabotage equipment the night of 27/28 February was chosen for the attack. Due to the discovery of the documents amongst the Freshman raid German security had been substantially raised, especially the bridge linking to the plant. It was decided that the team would descend into the valley and climb the opposite side then follow a rail line into the plant. Thanks to intelligence gleaned from workers inside the plant the men were able to gain access to the plant without alerting the German guards. However a caretaker was disturbed but he was happy to let the men continue their sabotage mission. Charges were placed and a British sub-machine gun was purposely left behind to show that it had been a Commando raid and therefore reduce local reprisals.

The men escaped without discovery and the machinery and stocks of heavy water were destroyed. Four of the raiding party decided to stay in the area to monitor the German response and act accordingly whilst two men moved to Oslo to continue work with the Norwegian underground, whilst the rest headed east to neutral Sweden.

Within two months the plant had been restored to full capability and this was relayed to SOE back in Britain. The chance of another raids success was minimal now that the Germans had increased the protection of the plant, but by early 1943 the USAAF had started to arrive in numbers in Britain, so a daylight raid, carried out by over 140 bombers was flown in November when the weather permitted a reasonable chance of target acquisition. However many of the bombs fell without result and the machinery itself was easily protected by the heavy concrete construction of the plant. However this caused the Germans to fear further raids and decided to transfer what stocks of heavy water they had produced and the machinery to a safer location in Germany. In order to transfer the remaining heavy water to the coast for transport to Germany it first had to travel a short distance from the plant to Mael. Here it would be loaded on to the steam ferry SF Hydro. Four men of the Norwegian resistance decided to sabotage the vessel whilst it was over the deepest part of lake Tinnsjo and deny the Germans the heavy water. The Germans decided to move the stock on a Sunday, lucky for the saboteurs as this would reduce any Norwegians travelling on the Hydro too.

The men snuck aboard the ferry on the evening of Saturday 19 February 1944 and proceeded to place an explosive charge in the bows of the ship. With the timers set the men withdrew.

The ferry left the station on time and by 10.30 am it was over the required area and the explosives blew as hoped. The ship started to list almost immediately, with those on deck managing to clamber aboard lifeboats or stumble over the side, however eighteen people were killed, including three Norwegian passengers, seven crew and eight German guards. The rest were picked up by locals using nearby boats to drag them out of the freezing water. The Hydro itself sank to below 400 metres, well beyond salvageable depth. The German Atomic programme, although never advanced, had taken a massive blow and would never recover.

SF Hydro at the rail dock on Lake Tinnsjo. She would be later sunk by Norwegian operative in order to deny the Germans heavy water from the plant at Vermork.

Elsewhere in Norway, particularly in the south and especially in and around Oslo, there quickly formed a strong resistance movement, the men and women of the country having a strong patriotic streak and being disappointed by how quickly their country had fallen to the Nazi oppressor joined in droves. With the leaders of what became known as ‘Milorg’ making contact with the government in exile, based in London, the resistance grew and grew.

At first underground papers were the only course of action these groups could take, counteracting the strong bias of the local press and the propaganda that abound through all sources of media. Nearly 300 such papers were founded but would only appear at random intervals as the men and women of the publications played a cat-and-mouse game with the Gestapo and their Norwegian counterparts.

To assist the Norwegian underground the SOE set up what would become known as the Shetland Bus. This was a group of Norwegian trawlers that were tasked with infiltrating and bringing back agents from occupied Norway. Using fishing trawlers they were ideally camouflaged and only lightly armed. They still ran the risk of having to cross the North sea at night, in winter under the constant threat of discovery, however they were extremely successful right up to the end of the war.

Armed resistance and sabotage in Norway itself posed other problems, with any act of sabotage usually met with harsh reprisals by the occupies. However, members of the Norwegian Independent Company No. 1 were highly successful, notably Max Manus, a veteran who had fought in the Finnish campaign of 1939–40. Having seen his country capitulate to the Germans in 1940 he actively worked in underground propaganda. He was then caught and injured trying to escape custody. He then dramatically escaped the hospital he was being treated in and arrived in Scotland for Commando training following an epic journey through Sweden, Soviet Russia, Africa and eventually to Canada.

Following training he was dropped into Norway along with a friend Gregors Gram. They were tasked with attacking shipping in Oslo harbour using Limpet mines, a small explosive charge, attached below the waterline of a ship by magnets.

The first raid was carried out on the evening of 28 April 1943, where they successfully sunk two transports and damaged a third.

In January the following year the decision was made to attack the large troop carrier Donau. This vessel had previously been used to transport Norwegian Jews to Germany where they were then sent onto concentration camps. This time canoes could not be used to approach the ship at night as security was high by the wharf. However, with great audacity Manus and his companion, Roy Nielson, entered the docks dressed as workmen. Whilst a colleague distracted the gate guards the two men were only given a cursory security check and proceeded to a small area beneath a lift where an insider had left a dinghy. The men took off their boiler suits to reveal full British uniform, so if they were captured reprisals would be reduced to the local populace. The explosives were placed and the men withdrew without any attention. At ten o’clock that evening the charges blew, and although the captain of the Donau tried to beach her, she was lost.