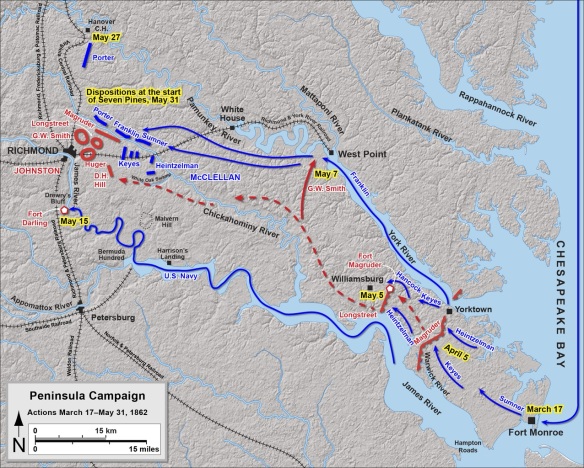

Peninsula Campaign, map of events up to the Battle of Seven Pines.

Western technological development transformed warfare and eventually swept away the Zulus’ world. Although many of the developments for which it is famed – the use of railways, telegraph and ironclad steamships – were not in fact new, the American Civil War is nevertheless often referred to as the first ‘modern war’. In terms of scale – with its mass armies, mass production and mass casualties – it certainly did represent modernity, but it was fought using largely Napoleonic tactical methods.

Following a disastrous opening to the war at First Bull Run (or Manassas Junction) in 1861, the Union appointed Major-General George B. McClellan as general-in-chief. His urgent task was to reorganize and train the Army of the Potomac, both for the defence of Washington DC and for future offensive operations with a view to capturing the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. ‘I can do it all’, McClellan assured President Abraham Lincoln. McClellan was known as ‘the Young Napoleon’ and affectionately as ‘Little Mac’ by his troops. He was an able administrator and trainer, but lacked resolution in the face of the enemy. At this time the Union intelligence service was run by the Pinkerton Detective Agency, founded by the ex-Glaswegian Allan Pinkerton, which later became renowned throughout the West. As a military intelligence bureau, however, it was hopelessly inadequate and provided wildly exaggerated reports of rebel strength in the area immediately south of Washington. Despite ample evidence to the contrary, Pinkerton reported Confederate forces as totalling 270,000 men, with 150,000 within striking distance of Washington. Little Mac refused to move until he had 270,000 men of his own.

Then in September rebel pickets were driven surprisingly easily from a position they had occupied within a few miles of Washington, revealing that the guns McClellan’s spies had assured him were trained on the capital were nothing more than stripped logs, painted black with wagon wheels tacked onto the side: one scornful reporter christened them ‘Quaker Guns’. Lincoln became so frustrated with Little Mac’s lack of resolution that when the latter was ill early in 1862, Lincoln told a White House war council that ‘if General McClellan does not want to use the Army, I would like to borrow it for a time’. Eventually however, McClellan was persuaded to take the offensive, albeit not via the direct route (which he remained convinced was strongly defended) but by a landing on the York–James peninsula and approaching Richmond from the south-east. The Confederates in front of Washington then abandoned their position to reveal an entire battery of Quaker guns at Centerville.

John Bankhead Magruder

On the peninsula Little Mac’s army, which totalled over 120,000 men, was initially faced by just 8,000 Confederates under John Bankhead Magruder, a lover of amateur theatrics known as ‘Prince John’ because of his lavish parties, fancy dress uniforms and pomposity (he even affected a ‘Horse Guards’ lisp). Friends recounted how he had tried to impress visiting British officers with his dinner and wines and displayed surprise when asked how much American officers earned, saying he had no idea and would have to ask his servant. This, like his entire lifestyle, was in fact a grand bluff; he had no independent income at all. Now he set to bluffing with a will.

Having anchored off Fort Monroe on 2 April 1862, Little Mac was initially filled with optimism but soon became despondent when the roads proved far worse than expected, slowing his baggage and artillery. Although Magruder had built his defence works with great energy, he had a thirteen-mile line to defend and there were simply not enough guns to cover it: he had been able to secure just fifteen, including light field pieces, and had barely sixty rounds for each. Therefore he made up the numbers with Quaker guns, hoping to replace them all with real ones in due course, but McClellan had arrived before he had a chance. So Magruder mixed Quaker guns with real ones along the line, hoping this would prove sufficient to delay the advancing enemy just enough, which with the cautious McClellan proved the case. With 67,000 men immediately to hand, McClellan could have brushed Magruder aside, but to add colour to the deception, Prince John conspicuously moved his handful of units about and ordered his bandsmen to play loudly after dark, while he himself rode ostentatiously about with a colourful following of staff officers. One battalion was sent to march along a road that was heavily wooded, except for a single gap in plain view of the Union lines. In an endless circle through the same clearing they swept past in seemingly endless array. ‘[We] have been travelling most of the day, seeming with no other view than to show ourselves to the enemy at as many different points of the line as possible,’ wrote an Alabama corporal, ‘I am pretty tired.’

It worked all too easily. Little Mac halted his infantry when it could have walked through the Confederate position at any point it chose and ordered his artillery to begin probing the defences. As early as 7 April he was telegraphing Washington to whine: ‘General J. E. Johnston arrived in Yorktown yesterday with strong reinforcements. It seems clear that I shall have the whole force of the enemy on my hands, probably not less than 100,000 men and possibly more.’ He believed therefore that his own force was ‘possibly less than that of the enemy’. No attack could succeed and, ‘were I in possession of their entrenchments and assailed by double my numbers I should have no fear as to the result.’ Despite intelligence reports that the enemy had no more than 15,000 men (which McClellan acknowledged as early as 3 April), the Young Napoleon believed that nobody, still less a professional soldier, would try to hold so precarious a line with so few. On 5 April McClellan declared, ‘I cannot turn Yorktown without a battle, in which I must use heavy artillery and go through the preliminary operations of a siege.’ In fact, by the 11th Magruder’s force still amounted to just 34,000 men and Johnston did not even reach Richmond until the 12th. When the Confederates eventually retired on the night of 3 May, just as Federal siege preparations were being finalized, their forces amounted to only 56,000 men. McClellan, who had been deeply impressed by his visit as an observer to the siege works of Sebastopol in the Crimea seven years previously, was probably more impressed with the works facing him than the apparent size of the garrison. Nevertheless, the diarist Mary Chesnut recorded that ‘it was a wonderful thing how [Magruder] played his ten thousand before McClellan like fireflies and utterly deluded him – keeping down there ever so long.’

Another Confederate general put on a command performance in May 1862. At Corinth, Mississippi, following the Battle of Shiloh, Major-General Pierre G. T. Beauregard sent ‘deserters’ to the Union lines with carefully rehearsed stories about his ‘offensive’ plans together with cavalry raids to spread panic and rumour. But he knew he could not hold the town if it came to a siege and decided that, in order to save his army, a retreat was necessary. Keeping his plans a secret from all but those who strictly needed to know, he arranged to evacuate the wounded, send on baggage and even remove the signposts beyond the town to hinder any pursuit. Meanwhile, with all his bands playing, a regiment was kept cheering the trains that arrived to take away his wounded, to convey the impression that reinforcements were arriving.

When the time came to tell the front-line soldiers that they were to withdraw, they were happy to join in the fun. They stole out of their trenches that night, leaving drummer boys with wood supplies to tend their fires and beat reveille in the morning, together with a single band to play at various points and a detachment to continue cheering the single train of empty cars that rattled back and forth in and out of the station all night. At 0120 hours that morning the Union commander, Major-General John Pope, sent word to his superiors that ‘the enemy is reinforcing heavily, by trains, in my front and on my left . . . I have no doubt, from all appearances, that I shall be attacked in heavy force at daylight.’ Instead, when daylight came, according to Brigadier-General Lew Wallace, the Union troops found ‘not a sick prisoner, not a rusty bayonet, not a bite of bacon – nothing but an empty town and some Quaker guns’. Worse, the dummy guns were served with dummy gunners fashioned from straw and old uniforms.

General Nathan Bedford Forrest and King Philip [the horse] by Mort Kunstler

Nathan Bedford Forrest, ‘the Wizard of the Saddle’, was described by William Tecumseh Sherman as ‘the most remarkable man our Civil War produced on either side’, although this did not prevent Sherman ordering that Forrest be ‘hunted down and killed if it cost ten thousand lives and bankrupts the federal treasury’. Forrest’s instinctive, brilliant command of cavalry included a flair for deception: he consistently managed to exaggerate his strength by a considerable margin. When he crossed the Tennessee River near Clifton on 17 December 1862, he needed to complete his task before the Union had time to concentrate forces for his destruction. Having captured some Union civilians, he drilled his men as infantry in their presence before allowing the civilians to escape, and in this way spread the rumour that his command included a large body of infantry. By the same token his men always carried a number of kettledrums which they kept beating to further reinforce the impression that there were infantry with him.

In April 1863 Forrest was given the task of defeating a Union raid into Alabama by Colonel Abel D. Streight. When Forrest finally cornered Streight and demanded his surrender, Forrest claimed to have a column of fresh troops at hand. ‘I have enough men to run straight over you,’ he said. Streight refused even to contemplate laying down his arms unless Forrest could prove this was so, but Forrest would not show his hand. Meanwhile, as previously instructed, Forrest’s artillery commander repeatedly brought his two guns over a rise in the road, into cover and round again, which Streight could observe over Forrest’s shoulder. ‘Name of God’, cried Streight at last, ‘how many guns have you got? There’s fifteen I’ve counted already.’ ‘I reckon that’s all that has kept up,’ said Forrest, looking round casually. Streight returned to his own line and soon afterwards surrendered to a force less than half the size of his own.

Forrest, who rose from private to lieutenant-general during the war, captured Athens, Alabama, on 24 September 1864 by bluff and sheer force of personality. He sent a flag of truce to Union Colonel Wallace Campbell with a note demanding immediate and unconditional surrender, like Cawdor at Fishguard, ‘to stop the effusion of blood’. When the two parties met, he insisted (as he often did) that if he was compelled to storm the works of the fort in which Campbell was ensconced it would result in the massacre of the entire garrison. Forrest claimed to have over 10,000 men, but Campbell would only agree to surrender if he could see them for himself. Forrest agreed to allow Campbell and one other officer to review his array and Campbell returned duly convinced that Forrest indeed commanded 8–10,000 men with nine guns, and that it would be murder to attempt further resistance. He had been stalling in the hope that reinforcements might arrive, but now agreed to surrender. In fact, Forrest’s command amounted to only 4,500, but he made the sum total of his command add up to 10,000 in the eyes of his opponent by a practice he often used. He displayed a portion of his troops dismounted, as infantry; once the Union colonel had passed to another detachment, these mounted and moved position to appear as cavalry. He also moved his guns about to give a similar impression. However, Campbell was not wrong about the arrival of reinforcements. These arrived shortly afterwards and were also compelled to surrender.