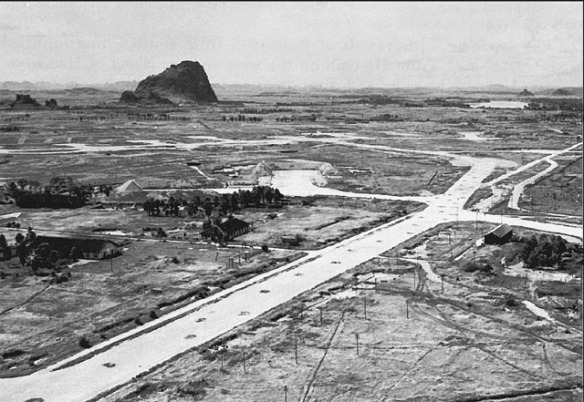

LIUCHOW AIRSTRIP as it looked when Chinese troops recaptured the airfield.

The Chinese Combat Command, headed by Maj. Gen. Robert B. McClure, was designed to make the advisory effort more effective in the face of Chinese practices and attitudes that had caused problems in the past. The key issue was leverage. McClure wanted every Chinese ALPHA Force commander down to regimental level to have an American adviser. If a Chinese commander refused to accept the advice of the American working with him, the matter would be referred to their next higher Chinese and American superiors, ultimately ending up with Chiang Kai-shek and General Wedemeyer. Any Chinese commander who continually refused to follow advice would be replaced or have American support withdrawn from his unit.

Personnel shortages prevented the system from being extended to the regimental level, but eventually all 36 divisions, 12 armies, and 4 group armies of the ALPHA Force received American advisers and liaison personnel, some 3,100 soldiers and airmen, all linked by radio. Each advisory team had about twenty-five officers and fifty enlisted men, picked from different arms and services so that qualified technicians from ordnance, logistics, and engineer specialties would be available to help the Chinese. Advisers also furnished technical assistance to the Chinese in handling artillery and communications, and American military medical personnel worked with Chinese medics, nurses, and doctors who generally lacked formal training. Each advisory team also had an air-ground liaison section, operating its own radio net to provide air support. At the unit level, the American advisers accompanied Chinese forces in the field, supervising local training as best they could and working with Chinese commanders on plans and tactical operations. In no case were Americans in command, and their influence depended primarily on their own expertise and the willingness of Chinese commanders to accept foreign advice. And, not surprisingly, in those Nationalist units which Chiang hoped to conserve for his expected postwar struggle against the Red army, operations against the Japanese were not pursued with great vigor.

Training, American officers believed, was the key to success. While the Chinese divisions received unit training from personnel of the Chinese Combat Command, U.S. troops assigned to the Chinese Training Center, under the command of Brig. Gen. John W. Middleton, trained individual soldiers and, in some cases, cadres of special units. Training Center members established and then operated service schools, prepared and distributed training literature, and gave technical assistance to those assigned to the Chinese Combat Command. Ultimately, General Middleton operated seven service schools and training centers, the majority located near Kunming. Of those, the Field Artillery Training Center was the largest and, at its peak some one thousand Americans were instructing about ten thousand Chinese in the use of American-supplied artillery.

In addition, the China theater operated a command and general staff school and a Chinese army war college; training centers for infantry, heavy mortar, ordnance, and signal troops; and an interpreters’ pool to teach English to the large number of Chinese serving as interpreters for the American advisers. Although the Americans wanted as many of the Chinese senior officers as possible exposed to the China Training Center coursework, only a small percentage of those officers actually attended the schools.

U.S. advisers also helped establish a Chinese services of supply (SOS) logistical organization to support the ALPHA Force. Emphasizing the movement of supplies from rear to front, it sought to supplant the traditional Chinese practice of cash payments and foraging. Of the approximately 300 Americans serving in the Chinese SOS headquarters, 147 officers and enlisted men worked in the Food Department, 84 served in the Quartermaster Section, and the rest were divided among ordnance, medical, transportation, communications, and other staff departments. In the field, 231 Americans manned a Chinese driver training school, and another 120 worked with various Chinese service elements. In a departure from standard practice, Chiang gave the American SOS commander, General Cheves, the rank of lieutenant general in the Chinese army and command of the Chinese SOS for the ALPHA divisions.

The ALPHA Force, concentrated around Kunming and commanded by General Ho Ying-chin, the former chief of staff of the Chinese army, gradually began to take shape. Wedemeyer hoped that U.S. assistance would transform its thirty-six divisions into a force capable of seizing the initiative from the Japanese in China. He believed that each one of the U.S.-sponsored divisions, with ten thousand men and its organic artillery battalion, would be more than sufficient to defeat a Japanese regiment.

Ultimately, Wedemeyer hoped to lay the groundwork for a Chinese offensive in the summer of 1945 that would recapture lost ground in the Liuchow-Nanning area east of Kunming and then drive on to capture a port in southeast China. At a minimum, such an offensive would tie down Japanese troops who might otherwise be sent back to defend Japan against an Allied invasion. Once a port was captured, the increased flow of supplies would enable Chinese armies to undertake a general campaign to clear all Japanese forces from the Asian mainland. Wedemeyer’s plan, code-named Operation BETA, seemed especially desirable in early 1945, when some American strategists expected that the Japanese, even with their home islands overrun, might make a final stand in China and Manchuria.

On 14 February 1945, General Wedemeyer submitted his plan for the Chinese offensive to Chiang Kai-shek, who immediately approved it. Wedemeyer’s plan made a number of assumptions: the war in Europe would come to an end in May; operations in the Pacific would continue as planned, and would force the Japanese armies in China to redeploy to the north and east; a four-inch pipeline under construction from Burma would be completed by July; and the Hump and the land route to China through Burma, which opened in February, would together be able to deliver 60,000 tons of supplies per month. The plan had four phases: the capture of the Liuchow-Nanning area; the consolidation of the captured area; the concentration of forces needed for an advance to the Hong Kong–Canton coastal region; and an offensive operation to capture Hong Kong and Canton. The Joint Chiefs of Staff eventually approved the plan on 20 April, but by that time it had been overtaken by other events in the China theater.

In late January and early February, the Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo revised its China policy. With the situation in the Pacific worsening, and with the increased possibility of both Japan and China being attacked from the sea, it ordered the China Expeditionary Army to focus on preventing an Allied invasion of China. Advance American air bases in China were to be destroyed, but other than that, only small forces would be permitted to launch raids into the interior. Instead, the Japanese command wanted to strengthen its forces in central and south China, particularly in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River between Shanghai and Hankow, about 450 miles to the west. To execute the new plan, General Okamura established three new divisions to reinforce the defenses along the coast of China. However, he also kept his remaining units concentrated in the interior. In late March, a renewed Japanese offensive began with the China Expeditionary Army attacking westward on a broad front between the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, with the objective of capturing the American air bases at Laohokow, 350 miles northeast of Chungking, and at Ankang, some 100 miles west of Laohokow. On 8 April, Laohokow fell.

The Chinese Army, 85 percent of which fell outside the ALPHA Force, was unable to counter the Japanese advance in any meaningful way. The heavily bureaucratic Nationalist government and army were simply too cumbersome to direct any effective and immediate military response. In the absence of coherent Chinese planning, Wedemeyer and his staff filled the gap. U.S. planners believed that Okamura would next move either toward the American air base at Chihchiang, 270 miles southeast of Chungking, or continue the push westward beyond Laohokow. General Wedemeyer thought the drive to Chihchiang more likely and planned accordingly. He immediately took a series of defensive measures aimed at preparing the American-sponsored units for quick action and ordered the Fourteenth Air Force to continue bombing attacks on enemy communications lines. If the Japanese could be delayed now, Wedemeyer hoped that beginning about 1 May a powerful Chinese-American offensive could sweep them back toward the coast.’