Subsequently, Roosevelt divided the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations into two parts. Lt. Gen. Daniel I. Sultan took command of the India-Burma theater, and Lt. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer arrived in China on 31 October 1944 to become the commanding general of the U.S. forces in the China theater and chief of staff to Chiang Kaishek. The Joint Chiefs of Staff instructed Wedemeyer to advise and assist the Generalissimo on all matters pertaining to the conduct of the war against the Japanese, including training, logistical support, and operational planning for the Chinese Nationalist forces.

Before World War II General Wedemeyer had served tours in the Philippine Islands and in China. More recently, his experience as a member of the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff gave him the perspective and experience needed to develop strategic plans for China. Furthermore, he had become familiar with the Chinese army and acquainted with Chiang Kai-shek while serving as Deputy Chief of Staff of the Southeast Asia Command under Lord Mountbatten, before his appointment to the China theater. Unlike his predecessor, Wedemeyer quickly established an excellent working relationship with Chiang.

The American forces in China were a varied lot, reflecting the diverse nature of their missions. The B–29s of the XX Bomber Command, under Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, were controlled by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, not General Wedemeyer. The long-range bombers had a strategic offensive mission, striking from their bases in India and China at targets as far away as Formosa, Manchuria, and southern Japan. Wedemeyer also had no direct authority over the China Wing, India-China Division, Air Transport Command, commanded by Brig. Gen. William H. Turner, charged with ferrying troops and supplies within China and flying the Hump.

Of those American forces under Wedemeyer’s direct control, the Fourteenth Air Force, commanded by Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault, was the most significant. Because of the weakness of Chiang’s army and the lack of adequate roads and railways, Chennault’s mixed force of fighters, medium and heavy bombers, and transport aircraft was vital to keeping supplies flowing to the Chinese troops and their American advisers and in attempting to halt Japanese excursions into Chinese-held territory. Other than air units, Wedemeyer had only a small number of ground force personnel. Most were advising and training parts of the Chinese army, particularly a number of American-sponsored divisions.

As much of the staff for the old China-Burma-India Theater of Operations had been located in India, Wedemeyer’s new headquarters was extremely small. Initially, he reorganized it into two main elements. A forward echelon in Chungking, the wartime capital of China, dealt primarily with operations, intelligence, and planning. A rear echelon at Kunming, some 400 miles southwest of Chungking and the China terminus for the Hump air supply line, handled administrative and logistical matters. The commander of Wedemeyer’s Services of Supply, Maj. Gen. Gilbert X. Cheves, headed the latter.

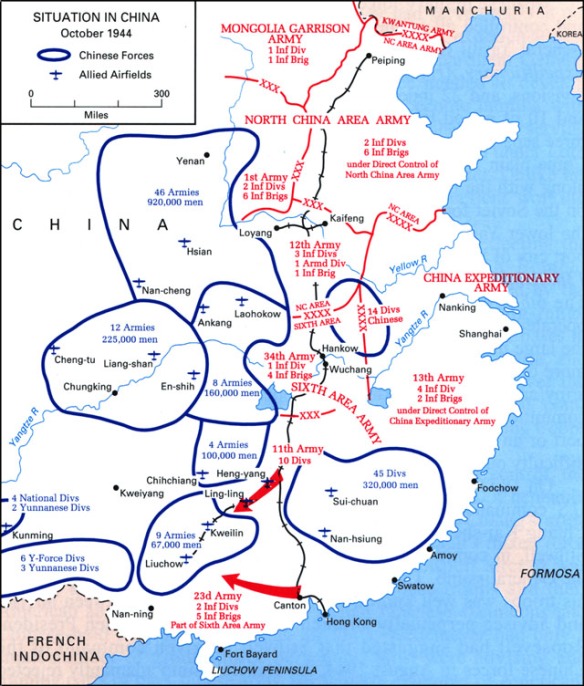

Almost immediately, Wedemeyer was faced with a major crisis. In October 1944, provoked by American bomber raids from China on southern Japan, the Japanese began a major offensive to eliminate the airfields used for staging the air attacks. On 11 November, less than two weeks after Wedemeyer’s arrival in China, the Japanese Eleventh Army captured Kweilin, 400 miles southeast of Chungking and one of the Fourteenth Air Force’s largest bases. The Twenty-Third Army, moving west from the Canton area, seized another air base at Liuchow, 100 miles southwest of Kweilin. From Liuchow the Japanese moved southwest toward Nanning, some 150 miles away. On 24 November the town fell, allowing the Japanese to establish tenuous overland communications across all of eastern Asia between Korea and Singapore. By mid-November many of the major airfields used by the U.S. Fourteenth Air Force and the XX Bomber Command in China had been occupied, and Japanese forces shifted their advance westward toward Kunming and Chungking. Both of these cities were critical: if Kunming fell, the Hump aerial supply line would be cut; if Chungking, Chiang’s wartime capital, was lost, the blow to Nationalist prestige and authority might be fatal.

In attempting to halt the Japanese offensive, the Chinese forces had performed poorly. Wedemeyer recognized that before the Chinese army could be successful, at least part of it must be transformed into an effective combat force. Under the threat of further Japanese advances against Kunming and Chungking, Chiang agreed to the creation of a force of thirty-six infantry divisions under a single responsible Chinese field commander and a combined Chinese-American staff. The divisions, which were referred to as the ALPHA Force after a plan of defense, code-named ALPHA, would be equipped, trained, and supplied by Americans.

Although Chiang’s agreement to the ALPHA Force plan was a major victory for the American advisory mission, Wedemeyer did not achieve all that he had sought. Chiang, concerned that Mao Tsetung might turn some of his three-million-man Communist military force against Nationalist strongholds, refused to permit the Americans to train more than thirty-six divisions, only about 15 percent of the total Chinese army. More significant, the Generalissimo kept many of his best soldiers out of the ALPHA divisions and in reserve near Chungking.

For an immediate defense against the advancing Japanese, Wedemeyer turned to Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force and also requested the return of two American-equipped and -trained Chinese divisions from Burma and India. But, fortunately for the hastily formed and relatively unprepared ALPHA force, the Japanese had outrun their supplies by mid-December and were forced to halt their advance to the west. Chennault’s airmen now began systematically attacking Japanese supply centers and railways to prevent a buildup of supplies to support additional Japanese offensives. More and better aircraft, including the new P–51 fighter-bombers with their great range, along with an increased flow of supplies over the Hump, allowed the Fourteenth to wage a heavy and sustained bombing attack whose cumulative effect on the Japanese was serious. The 6th Area Army, most immediately affected by the air strikes, concluded that the severe shortage of fuel and the impending collapse of rail communications might soon force them to abandon south China, an estimate of which the Americans and Chinese remained ignorant.

Japanese supply difficulties and the Fourteenth Air Force’s raids had bought part of the time needed for the ALPHA divisions to be turned into an effective combat force. Moreover, increased tonnage flown over the Hump and the imminent success in Burma, which would reopen the ground supply route to China, made it likely that the equipment and supplies for the ALPHA divisions would arrive in a timely manner. The missing piece in creating the ALPHA Force was a more effective organization to train, supply, and control the operations of the divisions. Recognizing this, General Wedemeyer, in January 1945, established the Chinese Combat Command and the Chinese Training Command.