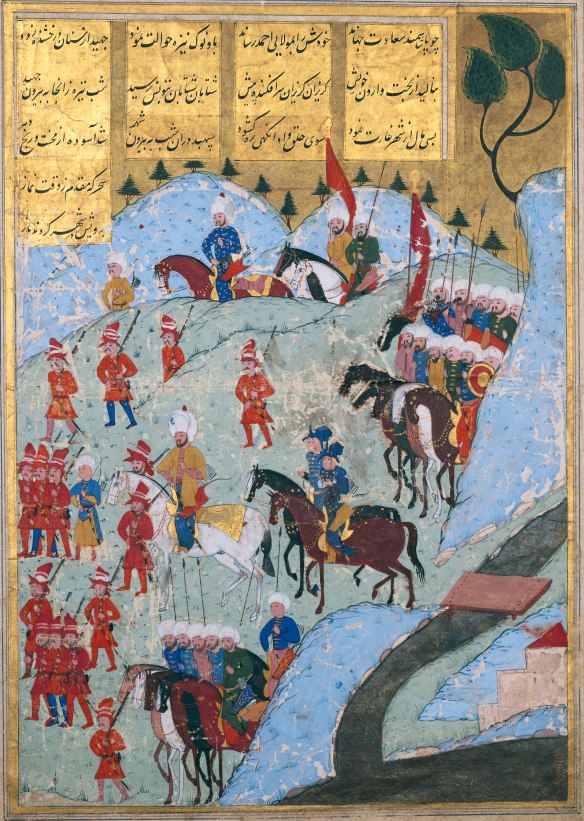

Ottoman troops (about 5,000 Janissaries) and Kabyle troops, led by Uluç Ali, Pasha of Algiers, marching on Tunis in 1569.

Sicily by Piri Reis, Kitab-i Bahriye (1526)

For all the excitement of her newfound wealth, Spain could not completely ignore her European responsibilities. Her chief enemies were the French and, of course, the Turks—though she also had to fight occasional wars with just about everyone else, including the English and the Portuguese, the Germans and the Dutch, and sometimes even the Papacy. None of these wars except those against the Turks had anything to do with Sicily, though the island was always obliged to make its contribution, whether in money, manpower or agricultural produce.

The second half of the fifteenth century, as we have seen, witnessed two cataclysmic events, one at each end of the Middle Sea: in the east, the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453—with the consequent closure of the Black Sea and, ultimately, much of the eastern Mediterranean—and in the west the gradual expulsion of the Moors from Spain in the years following 1492. Both led to a proliferation of rootless vagabonds—in the east Christians, in the west Muslims—all of them ruined, disaffected and longing for revenge; and many of them adopted the buccaneering life. The Christians would normally establish their bases in the central Mediterranean—in Sicily, or Malta, or among the countless islands off the Dalmatian coast. The Muslims, on the other hand, could only join their coreligionists in North Africa. Between Tangier and Tunis there were some 1,200 miles and, in what was still for the most part a moderately fertile and well-watered coastal strip, several almost tideless natural harbors ideal for their purposes. And so the legend of the Barbary Coast was born.

Until the middle of the century, the Sicilians had maintained friendly relations with North Africa, and there was profitable commerce in both directions. After the fall of Constantinople, however, conflict between the Spaniards and the Turks became inevitable and Sicily, instead of occupying the center of the main trade route between Europe and Africa, found herself in what almost amounted to a no-man’s-land. Her parliaments consistently petitioned Spain to be allowed to preserve the old commercial links with the cities of the coast, but the ultra-Catholic Ferdinand refused to allow his subjects any dealings with the infidel, and such trade as continued to exist was carried on largely by smugglers or pirates.

Of these pirates by far the most powerful were Kheir-ed-Din Barbarossa and his brother Aruj. Born on the island of Mytilene (the modern Lesbos) to a retired Greek janissary—like all janissaries, he had at first been a Christian before his forcible conversion to Islam—they possessed not a drop of Turkish, Arab or Berber blood, a fact to which their famous red beards offered still more cogent testimony. Acting on behalf of the Ottoman Sultan Selim I, they effortlessly conquered Algiers as early as 1516. Aruj died two years later; Kheir-ed-Din, however, went from strength to strength, ruling Algiers and its province technically in the Sultan’s name but in fact wielding absolute power in the region. In 1534 he had the temerity to attack Tunisia, toppling the local sultan Moulay Hassan and annexing his kingdom; but here he overreached himself. He might have seen that the Emperor Charles V could not conceivably accept the annexation of a country less than a hundred miles away from the two most prosperous ports of western Sicily—Trapani and Marsala—and only a very little more from Palermo itself. The idle and pleasure-loving Moulay Hassan had constituted no danger, but now that Barbarossa was in Tunis the Emperor’s own hold on Sicily was seriously threatened.

As soon as he heard the news, Charles began to plan a huge expedition to recover the city. His invasion fleet would number ships from Spain, Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, Genoa and Malta, which—with Tripoli—he had given in 1530 to the Knights of St. John following their eviction from Rhodes. The Spanish contingent—estimated at some four hundred ships—sailed from Barcelona for Tunis at the end of May 1535. Against such an armada Barbarossa knew that he had no hope of retaining his hold on the city. On July 14 the fortress of La Goletta that defended the inner harbor was stormed by the Knights, and a week later a considerable number of Christian prisoners—there are said to have been 12,000, but this sounds unlikely—managed to smash their way to freedom and flung themselves on their erstwhile captors. Tunis was effectively won—and now it was Barbarossa’s turn to flee. Moulay Hassan was formally reinstated in the empty shell of his city and the Spaniards, having repaired and refortified La Goletta, declared it Spanish territory and equipped it with a permanent garrison. The expedition, the victorious Christians all agreed, had been a huge success. Tunis was once again in friendly hands, Sicily was again secure, thousands of their coreligionists had been freed from captivity, and—best of all, perhaps—the formerly invincible Barbarossa had been conclusively defeated.

Or so they thought. In fact, the great corsair was in mid-career. He was to score several more major victories, including, in 1541, one that resulted in the almost total destruction of another Spanish invasion fleet, directed this time against Algiers. He also annexed in the name of the Turkish Sultan—now Süleyman the Magnificent—many formerly Venetian islands. Soon Süleyman gave him the command of the entire Ottoman navy; the erstwhile pirate was now Supreme Admiral. He died in 1546—peacefully in Istanbul, where his tomb may still be seen.

After Barbarossa’s death the fighting went on, with the Turks launching a series of devastating raids along the Sicilian and North African coasts. In 1551—only five years after the old corsair’s death—they took Tripoli, and in 1560 destroyed twenty-four out of forty-eight Spanish and Sicilian galleys off Djerba. The pendulum swung back briefly in 1565, when the Knights of Malta heroically defended their island for four months against everything that Sultan Süleyman could throw against it; once again, however, theirs was an isolated triumph. Ten years later, Venetian Cyprus was to fall to Süleyman’s son Selim; its commander, Marcantonio Bragadin, was subjected to appalling tortures, culminating in his being flayed alive. Of the old Venetian trading colonies of the Mediterranean, only Crete remained.

In 1571 Christian Europe took its revenge, when Spain, Venice and the Papacy smashed the Turkish navy at Lepanto, Sicilian ships as usual playing their part. But—the question is still being debated today—was Lepanto indeed, as many have claimed, the greatest naval engagement between Actium—fought only some sixty miles away—and Trafalgar? In England and America, admittedly, its continued fame rests largely on G. K. Chesterton’s thunderous—if gloriously inaccurate—poem; but in the Catholic countries of the Mediterranean it has broken the barriers of history and passed into legend. Does it, one wonders, altogether deserve its reputation?

Technically and tactically, yes. It was the last major battle ever fought exclusively with oared galleys; after 1571, naval warfare was never the same again. Politically, on the other hand, it was a flash in the pan. The battle did not, as its victors hoped, mark the end of the pendulum’s swing, the point where Christian fortunes suddenly turned, gathering force until the Turks could be swept back into the Asian heartland whence they had come. Instead, those Turks were to capture Tunis in the following year, leaving Oran as the only port along the entire coast remaining in Spanish hands. Venice did not regain Cyprus; only two years later she was to conclude a separate peace, relinquishing all her claims to the island. Nor did Lepanto mean the end of her losses; in the following century Crete, after a twenty-two-year siege, was to go the same way. As for Spain, she did not even appreciably increase her control of the central Mediterranean; only seventeen years afterward, the historic defeat of her Great Armada by the English was to deal her sea power a blow from which it would not quickly recover. And, try as she might, she was never able to break the links between Constantinople and the Moorish princes of North Africa; within a few years the Turks were to drive every Spaniard from Tunis, make vassals of the local rulers and reduce the area—as they had already reduced most of Algeria to the west and Tripolitania to the east—to the status of an Ottoman province.

But the real importance of Lepanto, for all those Christians who rejoiced in those exultant October days, was moral. The heavy black cloud which had overshadowed them for two centuries and which since 1453 had grown steadily more threatening, to the point where they felt that their days were numbered—that cloud had suddenly lifted. From one moment to the next, hope had been reborn. The Venetians were eager to follow up their victory at once; the Turk must be given no rest, no time to catch his breath or to repair his shattered forces. This was the message that they propounded to their Spanish and papal allies, but their arguments fell on deaf ears. Don John of Austria, King Philip’s bastard half-brother and the Captain-General of the combined fleet, would probably have been only too happy to press on through the winter, but his orders from Philip were clear. The allied forces would meet again in the spring; till then, he must bid them farewell. He had no choice but to return with his fleet to Messina.

In the years after Lepanto, piracy along the Barbary Coast continued unabated. Sicily suffered; in her dangerously exposed position she could hardly have done otherwise. At this time she was enduring two or three major attacks each year; no farmhouse within ten miles of the sea was safe, and in 1559 and 1574 there were raids on the outskirts of Palermo itself. On the other hand, she probably gave as good as she got: of the worst offenders among the corsairs, rather more than half seem to have been Christians, including a good many Sicilian privateers. The Knights of St. John too, despite the huge Maltese crosses that they wore with such pride, were by no means averse to piracy and smuggling on a formidable scale. Spain did everything possible to dress up the whole thing as a Crusade, but of course it was nothing of the kind: the Turks had many a Christian working or fighting on their side. In 1535 Francis I of France had actually allied himself with Barbarossa, and in 1543 had allowed the Turkish fleet to winter in the harbor of Toulon; and—though few were aware of the fact—there was even a brief moment when Charles V himself considered abandoning Algiers and the greater part of Tunis and Tripoli to the old pirate. Fortunately, he thought better of it.

The fact of the matter is that Charles was becoming bored with the Barbary Coast. Obviously, it could never be reconquered; and the constant need to protect Spanish interests was proving ruinously expensive in ships and manpower while achieving only very moderate success. In any case, by the time of his abdication in 1556 and the succession of his son Philip II, the political situation was beginning to change; and by the end of the 1570s Philip saw that he must cut his losses in the Mediterranean and concentrate his strength in northern Europe for deployment against his new enemies, England and the Netherlands. Now Sicily was left practically undefended, and the raids from the Barbary pirates became worse than ever—worse still after the defeat of the Armada in 1588, when Philip’s entire navy was lost and for many years Spain effectively ceased to be a maritime power.

Why, it might be asked, did the Sicilians not make a greater effort to defend themselves, or indeed to take the offensive against their enemies? Largely, because they no longer possessed a proper navy. Their last, of which they could be genuinely proud, had been the creation of King Roger, some three hundred years before. But after the end of Sicilian independence there was little incentive to build ships—an industry that Roger had largely confined to his mainland territories, where there were plenty of good navigable rivers for transporting timber from the inland forests down to the shore. In Sicily such rivers did not exist. This is not to say that there was no shipbuilding at all on the island: the industry continued after a fashion, principally in Palermo and Messina, and oared galleys were still the rule. But galleys needed crews, and these were increasingly hard to find. They called for six men to each oar, some two hundred in all for a large vessel. Some were slaves or convicts, some were press-ganged, some were so-called volunteers. If food ran short, one or two of them might be thrown overboard. All were chained night and day.

Meanwhile, piracy no longer stopped at the Strait of Gibraltar: the corsairs, both Christian and Muslim, had found a new and highly lucrative occupation—that of slave-running along the West African coast, subsequently exporting the captured slaves to Europe. Once again, the Sicilians were deeply involved—and, as far as we can judge, with a clear conscience. Had not the Emperor himself decreed that all infidels taken at sea could be considered slaves? Surely, then, the same must apply to those rounded up on land. So profitable was the trade that the slavers saw no reason to confine their activities to infidels; by the 1580s, several captains—including at least two Englishmen—were doing excellent business buying and selling Christian prisoners along the coast.