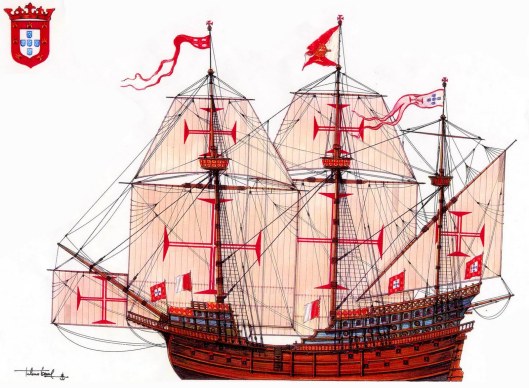

Flor de la Mar – Portuguese Carrack – flagship of D. Francisco de Almeida in the battle of Diu.

Approximate positions at sunset on the eve of the battle.

Battle of Diu.

When the Portuguese Fleet hove into view on February 2, 1509, the Muslim tactical discussion was riddled with hesitation and distrust. The Muslim fleet consisted of six Mamluk carracks and six galleys, four Gujarati carracks, Ayaz’s fustas, now reduced to thirty, and possibly seventy light vessels from Calicut. They had some four to five thousand men. The ships were nestled inside the mouth of the river on which Diu lay, in a situation analogous to that at Chaul. There was strong disagreement about how to proceed.

Hussain wanted to take the fight to the enemy early, while the Portuguese were still unprepared after a long voyage, and to engage them out at sea. Ayaz saw this as an excuse for the Egyptians to cut and run if the fight went badly, which he was certain it would, leaving him to face the consequences alone. He insisted that they fight within the river, protected by shore guns and potentially with the help of the townspeople—which would give him the chance to escape overland. He refused to allow his ships or those of Calicut to sail out. With Almeida’s threatening message ringing in his ears, he judged it best not to attend the battle at all, citing urgent business elsewhere. Hussain promptly called his bluff by sailing out and ordering Ayaz’s carracks out as well. Ayaz, summoned back to the city by messenger, then countermanded the order. There was a stalemate. The two commanders were to be shackled together and hobbled by mutual mistrust. Hussain, after a fruitless long-range artillery duel out at sea, was forced to accept the inevitable and fight inside the river. Ayaz was compelled to participate, again hoping to make just a show of battle while minimizing both his involvement and his losses. He could have barred the Portuguese altogether by raising a chain that closed the harbor; they would have been forced to turn back. The fact that he did not was probably a fine reckoning: he calculated that doing so would be perceived as a hostile action by Almeida for which he would pay sooner or later; he may have also calculated that the destruction of the embarrassing Mamluk fleet would be to his advantage and that he could one way or another strike a peace deal with the viceroy.

These suspicious cross-purposes left the Muslim fleet again adopting a defensive position, similar to that at Chaul. The carracks were anchored in pairs close to the shore in line, bow forward; first Hussain’s six carracks, then the galleys, then the Gujarati carracks. The fustas and light-oared ships from Calicut stayed farther upstream, with the aim of falling on the Portuguese from behind once they were engaged with their big ships. The shore guns would provide further covering fire. It was assumed that the enemy would repeat the tactics from Chaul; hungry for honor, they would grapple their opponents rather than blast them from afar.

Matching tactical discussions were taking place on Almeida’s ship. The viceroy was emphatic that this battle was the critical moment for Portuguese fortunes—“be certain that in conquering this fleet we will conquer all of India”—and that their whole presence there was hanging in the balance. He wanted the honor of leading the attack on Hussain’s flagship in person. However, the captains objected to this. Given the death of Lourenço, they firmly resisted Almeida’s desire to endanger his own life in this way. It would be better for him to control the battle from his flagship, the Frol de la Mar, and to leave others to take the initial hits. It was the first sign that they had learned from the debacle at Chaul. They refined their tactical sense in other ways. Cannon fire was to play a part in the battle. They would place their best archers and sharpshooters in the crow’s nests, insure against contingencies—materials to plug holes and water to put out fires would be prepared, and men on hand to do so—then attack as before: carracks would tackle the Muslims carracks, galleys their galleys. The powerful Frol de la Mar was to be a floating gun platform, stripped of soldiers. Its skeleton crew of sailors and gunners would pulverize the ships and specifically block a counterattack from the rear by the Muslim oared vessels. Some of the lessons of the German master gunner at Chaul had been absorbed.

Dawn. February 3, 1509. The ships waiting for the breeze and the tide to enter the shallow channel of the river. The viceroy sent each captain a message:

Sirs, the Rumes will not come out, since so far they have not done so. Therefore recalling the Passion of Christ, keep a sharp lookout for the signal that I will make when the sea breeze starts blowing, and we will go and serve lunch to them; and above all, I recommend that you take great care…that you escape from fire, should the Muslims set it to their own ships to burn them with yours or to drag you to the shore cutting their anchor cables.

Two hours later, the breeze began to rise. A light frigate passed down the line of ships. At each one, a man stepped aboard and read the viceroy’s proclamation to the assembled company. Almeida had composed for a rapt audience a rhetorical and heart-stirring message, gravid with a sense of destiny and holy war:

Dom Francisco d’Almeida, viceroy of India by the most high and excellent king Dom Manuel, my lord. I announce to all who see my letter, that…on this day and at this hour I am at the bar of Diu, with all the forces that I have to give battle to a fleet of the Great Turk that he has ordered, which has come from Mecca to fight and damage the faith of Christ and against the kingdom of the king my lord.

He went on to outline in ringing terms the death of his son at Chaul, the attacks on Cannanore and Cochin, the enmity of the king of Calicut “with the great armada which he has ordered to be sent.” He emphasized the peril and the need “to prevent the massive danger that will follow if these enemies are not punished and wiped out.” It was not just victory, it was annihilation that Almeida was seeking to inflict, in the course of which those who died on the Portuguese side would be martyrs. Though there are no records of the preparations on the Muslim ships, it is highly likely that similar calls to martyrdom in the name of God were being made.

As the herald passed down the line, he was also instructed to read out to the men on each ship a list of promises and rewards that would follow a victory—from the knights who would be elevated to the higher nobility, to the convicts whose sentences would be wiped clean. In the name of slaves who died in the battle, payments would be made to their owners; if they lived, their reward would be freedom. All were granted permission to loot when the battle was won.

With the breeze rising, the men were fired up for battle. The Frol de la Mar fired a shot to signal the advance. In the Muslim camp, they had also made their preparations. The ships were draped with nets to hamper boarding and allow men to throw missiles down on their attackers; their sides were fitted with thick boards to provide further protection, and their hulls above the waterline were draped with wet bags of thick cotton stuffing to hinder the operation of fire.

With their traditional war cry of “Santiago!” the Portuguese unfurled their flags. The ships moved into the channel to the blare of trumpets and the thunder of drums. The Muslim guns were readied on the shore and an island across the channel as the fleet passed through. Almeida had chosen his oldest vessel, the Santo Espirito, to lead the way, sounding as it went, and to take the first hit. Caught in the cross fire from both sides, “over everything a rain of shots, falling like a rain of stones,” the deck of the Santo Espirito was swept clean. Ten men were killed, but the fleet passed on through the neck of the channel and turned one by one to bear down on their chosen targets.

The prime objective for the lead carracks was the enemy flagship, always the key to a battle. This time the Portuguese intended to make wiser use of their artillery. The Santo Espirito steadied itself as it approached and fired at the anchored carracks at close range. A direct hit on the ship beside Hussain’s tore a hole in its flank; the listing vessel keeled over and sank, drowning most of the crew, to the cheers of the attackers. Rapidly the Portuguese closed on the flagship in groups of two. Farther down the line, battle was also being joined—carracks against carracks, galleys against galleys. Upstream Ayaz’s light fustas waited to advance on their enemies from behind.

There was a confused roar as the ships converged: the Muslim vessels anchored, waiting for the hit; the Portuguese turning broadside to fire at close range before tackling their foes; the Egyptians replying as best they could. The sun was blotted out, “the smoke and fire so thick that no one could see anything.” In the accounts of the chroniclers, it was a scene from the end of the world: the roar of the guns “so frightening that it seemed to be the work of devils rather than men”; “an infinity of arrows” ticking through the thick smoke; the battle cries of encouragement calling out the names of their gods, Christian and Muslim, the names of saints; the screams of the wounded and the dying “so loud that it seemed to be the day of judgment.” Closing accurately on targets was made difficult by the velocity of the current and the stiff breeze; some vessels smashed directly into their chosen opponents with a juddering impact; some only hit glancing blows and were swept on; others overshot their targets altogether and were carried upstream, temporarily out of the fight. It was clear that Hussain had skilled gunners and good cannons on his carracks—many of whom were European renegades—but their field of fire was hampered by their static forward-facing position, and he had far fewer experienced fighting men.

Boarding parties on the forecastles of Almeida’s ships were readied to leap at the first impact, when grappling hooks were flung across to tether the ships together, then reeled in by the slaves. The shock of the collisions was explosive. The Santo Espirito, despite being hit in the channel, advanced on Hussain’s flagship, the key prize and the eye of the battle. Men jumped across almost before the ship was secured and battled their way up the deck. Above them, clinging to the net, Mamluk archers rained down missiles; then the captain of the Santo Espirito, Nuno Vaz Pereira, led a second force across. It looked as if Hussain’s ship must fall, but in the smoke and confusion reversals of fortune were sudden. One of the other Egyptian carracks, maneuvering on its anchor cables, attacked the Santo Espirito from the other side, leaving it sandwiched between two Egyptian ships. At once attack switched to defense; the Portuguese were forced to abandon their prize and protect their own vessel. In the heat of the battle, Nuno Vaz, insufferably hot in his plate armor, lifted his throat guard to take a breath of air and was hit by an arrow. He was carried below, mortally wounded. It was a critical moment for the flagship fight; the Portuguese wavered. Then a second ship, the Rei Grande, slammed into the flagship from the other side and a fresh wave of men stormed aboard and managed to pull down the scrambling net, trapping those clinging to it inside. The initiative shifted once more.

Similar fights were in progress all down the line of carracks; having fired off their cannons, the Portuguese fell upon their foes with reckless bravery. The small Conceicão attempted to board another high-sided carrack; twenty-two men leaped aboard, including Pêro Cão, its captain, but the Conceicão was swept on past, isolating the men on the enemy ship, where they were heavily outnumbered. Cão tried to outflank their attackers by crawling through a porthole and was promptly decapitated as his head emerged. The remaining men holed up on the forecastle and resisted until they were rescued in a further assault by other ships. On the São João, heading for another Mamluk vessel, a dozen men waiting for the strike had sworn an oath to leap across together and do or die. The São João smacked into its target so hard that it bounced back and was deflected. At the moment of the leap, only five made it across and were immediately outnumbered; three were shot dead by archers, but the other two secured themselves in the hold behind screens and could not be winkled out. Despite losing blood from arrow wounds and wooden shrapnel, they fought on, killing eight men who tried to pry them out and finally being rescued more dead than alive when the ship was taken.