Sobekneferu

This quotation, which comes from the Middle Kingdom Instruction of Amenemhat I, makes it clear that the ancient Egyptians considered it unlikely for women to be in charge of troops; throughout Egyptian history non-royal women are non-combatant. Goddesses, however, were very different, possibly relating to their androgynous nature or perhaps a result of their apartness from human society. Queens, who took on the role of goddesses, that is, women who were the ‘King’s Principal Wife’ or the ‘King’s Mother’, might claim certain aspects of the warring goddess. Queens who took the role of kings, as sole ruler, naturally took over this masculine aggressive role as upholders of maat.

From the Predynastic Period onward, non-royal women, unlike men, were not buried with projectile points, and throughout Egyptian history, there are depictions of men carrying arms, but very few of women. Women are rarely shown carrying any sort of dangerous object which could be used as a weapon. In tomb paintings men are shown holding sickles, or are shown as butchers with knives, cutting joints of meat or butchering cattle. Women did not take these roles and did not prepare meat. When shown carrying out agricultural work, they do not carry sickles. Unlike boys, girls are not shown wrestling, and in every case, all depictions of soldiers are men.

The exceptions to the rule regarding women using weapons appear in the Old Kingdom and these are largely depictions of foreign women. A Sixth Dynasty representation of a besieged town, in the tomb of Inti at Deshasha, shows a woman defender stabbing a bowman with a dagger. Several of the male defenders seem to have beards, thus revealing that they are foreign. The foreign nature of the women is reinforced by a parallel scene from the Saqqara tomb of Kaemhesit which shows women in a siege situation, but none of them appear to be taking an active stance. In this scene the women are clearly foreign, wearing non-Egyptian clothing. Finally, there is the case of the Sixth Dynasty female guard called Merinebti-ankhteti of the pyramid cult of Teti, although here there is no evidence to suggest that she was foreign. Such guards were not mere doorkeepers, as the lady was given a tomb of her own.

Exceptions to the non-aggressive woman also occur later, but only in the royal family. The ‘King’s Principal Wife’ and the ‘King’s Mother’ are shown mirroring aggressive goddesses. However, such women, as far as we know, were rarely credited with being engaged in warfare, though there appear notable exceptions at the end of the Seventeenth Dynasty and beginning of the Eighteenth. Nefertiti is shown smiting the female enemies of Egypt, a pose usually reserved for the king. Although it has been surmised that she may have ruled at the end of the Amarna period as a king, this particular scene does not prove that the queen was engaged in warfare. Smiting scenes are more a demonstration of power and destruction of enemies, a ritual, than of engagement in warfare.

There is also the case of the mysterious lady Ahhotep (here called Ahhotep II to distinguish her from Ahhotep I, the mother of Ahmose I). This lady, a possible warrior queen, remains something of a mystery; her tomb was discovered in 1859 at Dra Abu el-Naga, Thebes and her coffin bears the title ‘King’s Wife’. Many of the objects found in the tomb bear the name of the kings Ahmose (1550–1525 bc) and Kamose (1555–1550 bc), so it is sometimes believed that these were her sons. However, her coffin does not have the title ‘Mother of the King’, so she had no son who became king by the time of her death. Her tomb has been dated to the reign of Ahmose, but prior to Year 22 of his reign. It has also been suggested that she was the wife of Kamose.

Ahhotep II was buried with a dagger and battle axe, as well as three golden fly pendants. Such pendants were given as awards for military valour, because good warriors were like flies – persistent, impossible to ward off and numerous. Although the dagger and battle axe found in the tomb are usually associated with her, they do not actually bear her name and since the Dra Abu el-Naga tomb was not her original burial place, it is possible that the objects belong to another person altogether. The axehead shows Ahmose smiting his enemies. However, the golden fly jewellery was closely associated with the queen, as the pendants were found inside her coffin.

Another Ahhotep, Ahhotep I, is also credited with aggression. She was the mother of Ahmose, honoured in a stela at Karnak as ‘one who pulled Egypt together, having cared for its army, having guarded it, having brought back those who fled, gathering up its deserters, having quieted the South, subduing those who defy her’.

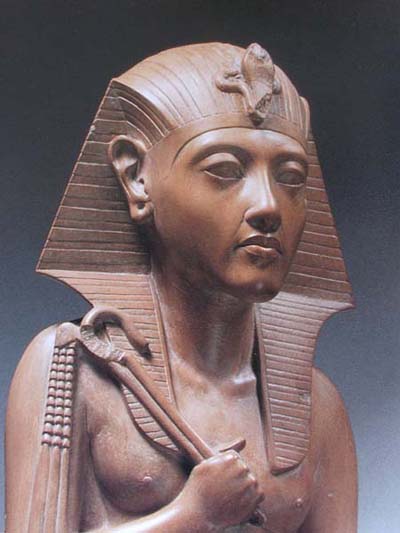

Naturally, queens ruling in their own right were endorsed as real kings partly through use of the warrior image since the king is shown as engaged in warfare in order to maintain cosmic order. Thus, the king’s title ‘Lord of Doing Things’, occurs on many items of warfare in Tutankhamun’s tomb. The feminine version of the title is used by only two women, both of whom ruled as kings, Sobekneferu and Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut took part in at least two military campaigns, but whether or not she led from the front, as kings claim to have done, is unknown.