On 15 August 1683 after the safe arrival of Gregorovitz and Koltschitzki, Lorraine at last had in his hands authoritative Viennese dispatches of the 4th, 8th and 12th of the month. He now knew more clearly the condition and prospects of the garrison. But Thököly’s marauders were still giving trouble in Moravia; and the irritating silence of the Passau government still vetoed a decisive move to the west. He reluctantly kept his station by the Morava, after sending forward the Grana and Baden foot-regiments under the Prince of Croy, with orders to prepare for the construction of a bridge at Tulln. Then Starhemberg’s message of the 18th, and his postscript of the 19th, reached him: the Turks had finally entered the moat in force. Next day, on the 21st, Lorraine set off with all his cavalry behind him.

Angern—Wolkersdorf- Stockerau: the road goes due east and west across the country, some twenty miles north of Vienna at its nearest point. From Stockerau, Lorraine himself went on ahead to examine the position opposite Tulln. The preparations for making a bridge here were well advanced; and the bridgehead on the other side of the river, the town of Tulln itself, had been reinforced by the few infantrymen he could muster. He returned to the camp at Stockerau and on the following morning, 24 August, detached a few troops to guard the plain farther north and east. The remaining regiments got ready to continue on their course to the west, when news suddenly came in that the enemy had appeared, not many miles distant; villages around the Bisamberg were on fire. Indeed, the Turks beaten at Pressburg a few weeks earlier were now moving forward again, out of Hungary and through the Little Carpathians, then riding west along the left bank of the Danube. With them came a sprinkle of Thököly’s Magyars, while volunteers from the main Turkish forces had crossed the river below Vienna to join them. Lorraine at once turned his men about. The enemy horse came in sight. Confused fighting began at two o’clock in the afternoon and the Turks were at first successful on both flanks, breaking through to the second line of Habsburg companies. But ‘our main body advanced in good order’ and its opponents retreated. The Magyars hurried back to the Morava, while other groups were observed trying to get away across the channels of the Danube. The boats (by which they had come) were miles downstream, few others could be found, so that possibly more men were drowned that day than were killed in the fighting beforehand. Such was the obscure, uncertain course of events sometimes labelled ‘the affair of Stammersdorf’, but the Turks evidently failed to interrupt the allied concentration north of the Danube. They tried next to rebuild the bridges leading across the river from Leopoldstadt, dismantled earlier by Lorraine. The water-level had fallen since then, so that the old timber foundations were accessible. Teams of Wallachian and Moldavian labourers duly arrived, and by the morning of 30 August a third of the main bridge was restored. Next day Lorraine struck. His own regiment advanced, and with the help of a battery swept the Turks out, making the bridge unusable.

Most of Lorraine’s troops were still at Stockerau, when he himself at last rode off to greet the King of Poland.

It was clear to all observers that the meeting of John Sobieski, Lorraine and Waldeck at Ober-Hollabrun, on 31 August, ended one phase of this campaign against the Turks and opened another. Leopold having forbidden Lorraine to move unaided against Kara Mustafa, it had been possible to concentrate simply on getting the Polish King and the German Electors into Austria. It was now necessary to choose a plan for the actual relief of Vienna, and to carry it out at once. The course of events at the end of August more or less settled the main issue. The Saxons and Poles were both present in force, some 35,000 men strong in Austria and Moravia, with 18,000 Franconians and Bavarians camped on the right bank of the Danube opposite Krems. The repulse of Thököly left Lorraine free to employ most of his 10,000 for the relief of Vienna. Even the difficult problem of transport across the Danube was nearly solved. Since those desperate days early in July, when the Lower Austrian Estates considered a proposal to destroy the bridge at Stein in order to keep the Tartars out of Krems, this crossing had proved its use to the troops and supplies coming down from the Empire. Moreover, two Turkish assaults on Klosterneuburg on 22 and 23 August failed ignominiously; it was therefore safe to proceed with the construction of another bridge at Tulln, half-way between Stein and Vienna. This plan was discussed at various times and by different authorities, ever since the Turks first settled down to the siege of Vienna. The Dutch engineer Peter Rulant reported in mid-August that the materials were ready, but that labour was scarce. Lorraine was insistent. Finally the military commander in Krems, Leslie, placed the business in the hands of a boastful but competent officer, Tobias Haslingen. By the end of the month the concentration of a massive relieving force south of the Danube, made possible by using the bridges both at Stein and Tulln, to be followed by the passage of this army through the Wiener Wald (along one route or another), was Lorraine’s immediate purpose. Sobieski had already agreed to the plan in outline.

It is not easy at this distance of time to thread one’s way through a confused series of meetings, held during the next few days in order to settle outstanding questions. After a final banquet in Sobieski’s company on 31 August—‘there was hardly a man there, but you could tell he’d been drinking,’ wrote Le Bègue—Lorraine returned to his camp at Korneuburg, and Waldeck to the neighbouring village of Stockerau. On 1 September rain began to fall, and fell through the day and night following; the advance of troops and the parley of generals were both hindered. A meeting at the north end of the Tulln bridge, arranged for the purpose of a private discussion between Waldeck and Lorraine, was put off. John Sobieski, who had firmly determined to keep Leopold away from the army in order to claim the supreme command, still debated whether he ought not at least to go to Krems for a personal interview with the Emperor. In fact he waited, and met Lorraine once again on the 2nd. On this occasion Michaelovitz was presented to him; the stout-hearted messenger, surviving his perilous journey from Vienna, had already delivered to Lorraine the letters written by Starhemberg and Caplirs six days earlier. The need for urgency was heavily underlined; but, apart from the weather, there is little doubt that the Habsburg generals and Waldeck were still groping for an answer to the problem of the command. If the Emperor expected to preside over the consultations of his allies, let alone to accompany the army on its march to Vienna, the chances of an effective partnership with Sobieski would be sharply reduced. The King of Poland insisted, to a certain extent he was bound to insist, on securing the prestige of leadership for himself. At the same time the Saxon Elector, and no doubt General Degenfeld (representing Elector Max Emmanuel) were determined to preserve the independent command of their own troops.

On 3 September John George left Horn, in order to meet his allies by attending the conference which he was told would take place at Krems. Halfway he had warning that the other leaders had changed their plans and were conferring in Count Hardegg’s castle at Stetteldorf, where the ground finally drops away into the waterlogged plain through which the Danube flows. He discovered, when he arrived, that one important meeting had already taken place while a second was still going on: the first, between Lorraine and Waldeck and the Bavarian Degenfeld, and the other a larger gathering with Sobieski, Herman of Baden and various generals present. It seems that Lorraine, Waldeck and Degenfeld had framed a set of questions and answers ‘to be deliberated’ by the whole conference. The King of Poland made no difficulty in agreeing to the main proposals; nor, when it came to his turn to speak, did the Elector of Saxony. The new Tulln bridges were assigned to Lorraine’s and Sobieski’s troops, the bridge at Stein to the Saxons. They were all to cross the Danube not later than 6 or 7 September, the whole army assembling in and around Tulln. The combined force would then cross the Wiener Wald in the area between the Danube and the River Wien; and this decision finally scotched the plan favoured by Herman of Baden, of a detour round the hills in order to attack the Ottoman army from the south, possibly cutting off its line of retreat into Hungary. But the great men at Stetteldorf touched in guarded terms on the most delicate problem of all. ‘If his Imperial Majesty does not appear,’ it was concluded, ‘the supreme command will rest with his Majesty the King of Poland, each prince retaining command of his own troops.’ The formula satisfied everybody, but Lorraine and Herman of Baden must both have realised that it was essential to keep Leopold at a safe distance. The Emperor, by his presence, would not compose discords; he would excite them. It must be assumed that they briefed Marco d’Aviano accordingly, when he reached Tulln a few days later.

After the conference John George moved west again to the village of Hadersdorf where he spent the next two nights. His regiments overtook him and reached Krems. On 5 September some of them were camped on an island in the Danube. They crossed the river, and covered part of the way along the south bank by the evening of the 6th, following behind the Bavarians and other troops of the Empire. At Tulln itself activity was intense. Haslingen relates, no doubt in exaggerated terms, how he had negotiated for a supply of money with the Estates of both Lower and Upper Austria, spent it freely on materials and equipment at the industrial centre of Steyr, and then succeeded in building two pontoon bridges at Tulln. Finally, with a labour force of 600 peasants and 1,000 musketeers, he hacked a way through the undergrowth of the flats between Stetteldorf and the river, so that troops could march down to the bridges without loss of time. The vanguard of the Poles appeared. Sobieski himself expressed admiration for what had been done, although he was preoccupied by the continuous repairs needed, which held up the wagons containing his supplies—a point of the greatest importance, because forage was very short in the ravaged country south of the Danube. He, like any spectator of the present day, was somewhat awed by the pace and weight of the main Danube current.

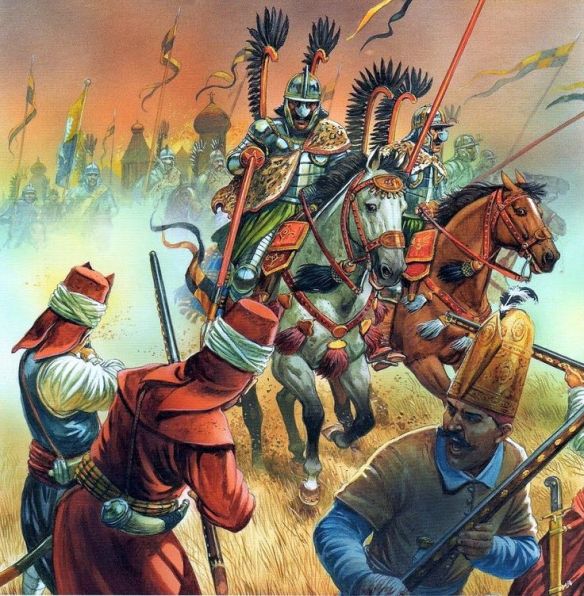

The concentration of troops on the level plain outside Tulln required three full days. The Bavarians, Franconians and Saxons took up positions nearest the Wiener Wald. The Habsburg troops drew up behind them; the Poles swung right after crossing the bridges and camped in the rear. In the town Marco d’Aviano bravely stoked up the enthusiasm for battle, and another council of war (on 8 September) discussed current problems, above all the dispositions for the march and for battle. A copy of an ‘ordre de bataille’ apparently drafted by John Sobieski has been recorded. If genuine (and it certainly contains some of the ideas expressed by the King in his correspondence) it must belong to an early phase in the negotiations. This document makes the distribution of troops in the camp at Tulln the basis of the order for battle. The Saxons, Bavarians and contingents from the Empire were to form the left wing marching closest to the Danube, the Habsburg soldiers the ‘corps de bataille’ in the centre, and to the Poles—coming up from their place in the rear of the camp—was assigned the place of honour on the right. It also stated that the infantry should move first in order to ease the progress of cavalry through heavily wooded hills, and then retire behind the horsemen when level ground in the neighbourhood of Vienna was reached. Guns were to be equally distributed between the different contingents, Habsburg, Imperial, and Polish; while German infantry units stiffened the Polish wing in return for the transposition of some mounted Polish troops to the left. One can only conclude that the council of generals, probably when Lorraine insisted, altered these arrangements in one fundamental particular; nor did the King of Poland leave on record any protest against the change. The Habsburg infantry, and part of their cavalry, were transferred to the left wing, with the Saxons placed next to them, while the Bavarians and troops of the Empire were posted to the centre. As before, the Poles remained on the right.