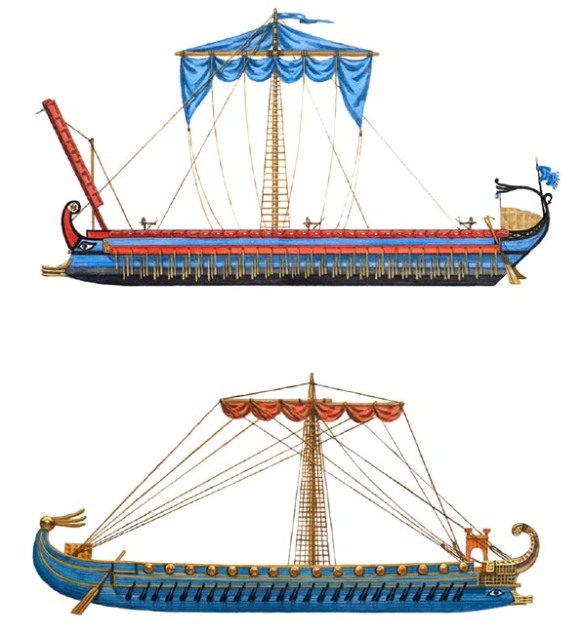

“Roman quinqueremes and Lembos biremes, 3rd to 2nd Century BC”

“Roman Triremes and Quadriremes, 2nd Century BC”

We do not know who took the initiative to start the new shipbuilding programme in Rome. An anonymous Greek source names Valerius Messala, the consul of 263, as the first person to realize that a new fleet was needed for ultimate victory. This may be true or it may be an attempt by his family to glorify one of its ancestors. According to Polybius, the decision was made in 261 and the ships were completed in the following year. Pliny states that the fleet was sailing sixty days after the first timber was cut.

Polybius’ description of the shipbuilding work is a mixture of myths and facts. On the one hand, he highlights the notion that the Romans were beginners and lacked the requisite knowledge:

When they saw that the war was dragging on, they undertook for the first time to build ships, a hundred quinqueremes and twenty triremes. As their shipwrights were absolutely inexperienced in building quinqueremes, such ships never having been in use in Italy, the matter caused them much difficulty, and this fact shows us better than anything else how spirited and daring the Romans are when they are determined to do a thing … When they first undertook to send their forces across to Messana … the Carthaginians put to sea to attack them as they were crossing the straits, and one of their decked ships [kataphract] advanced too far in its eagerness to overtake them and, running aground, fell into the hands of the Romans. This ship they now used as a model, and built their whole fleet on its pattern … if this had not occurred they would have been entirely prevented from carrying out their design by lack of practical knowledge.

It is possible that quinqueremes had never been built in Italy before. Yet constructing such ships should not have been a problem for the Romans as they could call on Syracusan expertise. Espionage played an important role in any ancient war effort and the capture of the Punic wreck allowed the Romans to analyse the latest development in Carthaginian shipbuilding. Besides, skilful shipbuilders could be hired, just as they had been by Dionysius I in Syracuse at the beginning of the fourth century BC:

He gathered skilled workmen, commandeering them from the cities under his control and attracting them by high wages from Italy and Greece as well as Carthaginian territory. For his purpose was to make weapons in great numbers and every kind of missile, and also quadriremes and quinqueremes, no ship of the latter size having yet been built at that time.

On the other hand, Polybius gives practical information on how the project was executed:

Those to whom the construction of the ships was committed were busy in getting them ready, and those who had collected the crews were teaching them to row on shore in the following fashion. Making the men sit on rowers’ benches on dry land, in the same order as on the benches of the ships themselves, and stationing the boatswain in the middle, they accustomed them to fall back all at once bringing their hands up to them, and again to come forward pushing out their hands, and to begin and finish these movements at the word of command of the fugle man. When the crews had been trained, they launched the ships as soon as they were completed, and having practised for a brief time actual rowing at sea, they sailed along the coast of Italy as their commander had ordered.

It was essential that the rowers kept pace. The training and exercising of crews is frequently mentioned in written sources and there is also some evidence in the pottery. Polybius describes a method generally used by fleets around the Mediterranean. Crews had multiple tasks: they could be used for operations on land as fighting soldiers, for instance, and for building siege engines. So it is likely that the new recruits were not only taught to row but were also given some basic military training.

Polybius does not provide any information about where the ships were built, who built them, where the timber came from or where the rowers were recruited from. Nor does he mention the harbours from which they sailed. The gaps in our knowledge need to be filled with the most plausible explanations. There are different opinions about the places where the ships were constructed. Some scholars believe that a centralized building programme was organized, as seems to be suggested by Polybius; others, stressing Rome’s lack of shipbuilding experience, believe that the project was spread over several ports, including Rome and the Greek cities of southern Italy.35 In my opinion, the ships were probably built in dockyards in Rome and then were stored in sheds in the Campus Martius, where the trireme fleet was presumably kept. Timber was available in Latium, Etruria and Umbria and could be taken to Rome using any of the tributaries of the Tiber or Anio. There must have been shipwrights in Rome and they could be hired, as they had been in Syracuse. The ships were probably launched in batches of around twenty-five and in two or three days all of them would have passed Ostia and be sailing south towards the Straits. The triremes required about 4,200 men and the quinqueremes around 35,000. The socii navales were obliged to send ships and rowers but Samnites were also recruited, as we know from information that has survived concerning their rebellion.

The naval organization comprised hundreds of thousands of people, including those working at the dockyards and those supplying sails, ropes, food and every other necessity needed on board. An expanding programme of shipbuilding was one of the most expensive policies that any ancient nation could adopt. In the case of Rome, the expansion was dramatic. In 311 the Romans had introduced triremes into their fleet and now, fifty years later, they had the resources to upgrade their fleet once again.

When the Roman fleet arrived in Sicily, Gaius Duilius, the consul leading the Roman land forces on the island, was called in to command it. He handed over his legions to the military tribunes before leaving to join the ships. The Romans began to get ready for a sea battle. Polybius states that, since their ships were badly-built and slow-moving, it was suggested that they should equip them with boarding-bridges.

There is no doubt about the historicity of the boarding-bridge or corvus. Polybius gives a description of its structure that Wallinga has corrected on some points. It worked as follows: at ramming distance, a gangway located on the bow was lowered onto the enemy deck and the soldiers ran across it in order to fight. The mechanism consisted of a pole with a pulley at the top. A rope ran through the pulley to a gangway that could be raised and lowered. Under the end of the gangway was a pointed pestle that, when the gangway was lowered, pierced the deck of the enemy ship and kept the two vessels locked together.

For anyone who follows Polybius’ view that the Romans were novices in maritime warfare and operated with poor-quality ships, the boarding-bridge has come to be seen as the key to their success, especially as, in his description of the battle at Mylae, he states that this device made combat at sea like a fight on land. However, it is doubtful whether the corvus had such a decisive impact. The Romans won their first battle on their way to Sicily without it, capturing many Punic ships, and the device is only mentioned twice in the sources: in the sea battles of 260 and 256 – thereafter there is no reference to it.

In my opinion, the corvus should not be seen in the context of the Romans’ inexperience in maritime warfare; there is a precedent in naval history that points to its real significance. Thucydides describes how the Athenians used grappling irons when they tried to break out from the harbour at Syracuse in 413. They boarded the enemy ships with soldiers and drove their opponents off the deck. According to Thucydides, the sea battle changed into a battle on land. The mass of troops on board made the Athenian ships heavy and hampered their manoeuvres. The Athenian innovation started a new era in naval tactics.

The boarding-bridge was a typical device in the Hellenistic period, when armies and navies were familiar with the strengths and weaknesses of their opponents and experimented with new fighting methods in order to surprise them. Once the Carthaginians had recovered from their surprise, they must have come up with a defence against the corvus but the sources do not describe the measures they took. Some of the technical details concerning the operation of the corvus remain uncertain, such as the angle at which it could be revolved, and it is not clear why the Romans stopped using it.

As for the alleged slowness of Roman ships, knowledge about the comparative performance of Roman and Carthaginian vessels is based on the outcome of the battle at the Cape of Italy where the Romans captured around fifty Punic ships and the remainder fled. The excessive weight of the Roman ships may have been due to the fact that they were loaded with troops, equipment and supplies, rather than a consequence of poor shipbuilding.

However, the Romans had been unable to take a few of the Punic ships. In this context perhaps the boarding-bridge should not be seen as a defensive tool but as a sign of the Roman determination to hunt down every enemy ship at every opportunity. By using the boarding-bridge, they could make sure that no Punic ships could escape.

We do not know how long the preparations for the battle took. Polybius states that the Carthaginians were ravaging the territory of Mylae and that Duilius sailed against them:

They all [the Carthaginians] sailed straight on the enemy, not even thinking it worthwhile to maintain order in the attack, but just as if they were falling on a prey that was obviously theirs … On approaching and seeing the ravens [corvi] nodding aloft on the prow of each ship, the Carthaginians were at first nonplussed, being surprised at the construction of the engines. However, as they entirely gave the enemy up for lost, the front ships attacked daringly. But when the ships that came into collision were in every case held fast by the machines, and the Roman crews boarded by means of the ravens and attacked them hand to hand on deck, some of the Carthaginians were cut down and others surrendered from dismay at what was happening, the battle having become just like a fight on land.

The first thirty ships were taken with their crews. Hannibal, who was commanding the fleet in the seven that had formerly belonged to Pyrrhus, managed to escape in the small boat. Trusting their swiftness, the Carthaginians sailed around the enemy in order to strike from the side or the stern but the Romans swung the boarding-bridges around so that they could grapple with ships that attacked them from any direction. Eventually the Carthaginians, shaken by this novel tactic, took flight. They lost fifty ships.

According to Polybius, Hannibal had 130 ships; according to Diodorus he had 200 ships involved in the battle. Diodorus says the Romans had 120 ships. Information about the type of ships that Scipio Asina lost at the Lipari Islands is not given in the sources but it seems probable that the Romans still had around 100 ships from their original fleet. Possibly they borrowed ships from their allies and made use of captured Carthaginian ships but no information is available. The brief description of the battle that has survived does not indicate whether the Romans arranged their ships in two lines or one. At first it seems the Carthaginians tried a diekplous attack. When that failed, they switched to a periplous attack but the Romans repulsed that too. If we accept Wallinga’s theory that the boarding-bridge could be revolved through 90 degrees, rather than freely in all directions as Polybius claims, then the Romans must have manoeuvred and regrouped their ships during the battle to defend themselves and to target the Punic ships as they approached. So, in practice, they continued to use the traditional tactics that were intended to sink enemy ships with rams and the deployment of the boarding-bridge did not make a significant difference to this aspect of the battle.