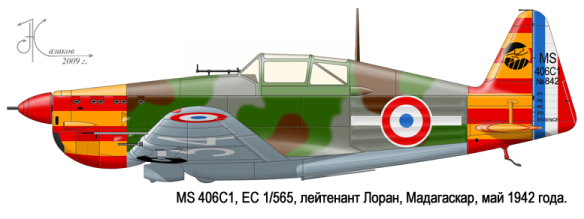

MS.406 C1 Unit: EC 1/565, Armee de l’Air de Vichy Serial: L-834 (N842)

Pilot – Lt.Laurant. Madagascar, May 1942. The unit’s ‘eagle’s’ head in disc insignia shown on the fin may have been black and yellow, as an alternative to that shown here.

Potez 63.11 Unit: ER 555 Serial: N377 (?-?76)

This aircraft was destroyed at Diego-Arrachart airfield, Madagascar on May 5th, 1942.

Before the new offensive on Madagascar got underway, there was another clash between Britain and France, in the shape of Operation Jubilee. Significantly, a substantial part of the invasion force, which was predominantly Canadian, comprised French-speaking volunteers from Quebec. It was a disastrous and somewhat ill-conceived gesture to show that Britain still had a sting in its tail. Over half of the 6,000 men that were involved in the operation failed to return home. Significantly, Pétain had congratulated the Germans for ‘cleansing French soil of the invader’.

Back on Madagascar, approaches had been made to the British stating that the bulk of the French on the island actually wanted to come to terms with the British, but that to simply surrender was out of the question. They had to succumb to an insurmountable show of force.

Plans to complete the conquest of Madagascar were already well advanced. But resources were still thinly stretched. The new invasion convoy and landings would only be covered by a single aircraft carrier, HMS Illustrious. HMS Indomitable had already left to assist Malta. This meant that the Royal Naval aircraft available for new operations amounted to 881 Squadron’s twelve Martlets, 806 Squadron’s six Fulmars and eighteen Swordfish belonging to 810 Squadron and 829 Squadron.

The plan was that Majunga (now Mahajanga) would be seized and the 22nd East African Brigade, with South African armoured cars, would push down the 270-mile road to Tananarive. There would also be two diversions; Commandos would land at Morondava, some 600 miles further south than Majunga. Once the landings at Majunga were established the British 29th Brigade would re-embark from Majunga and be taken all the way around the island, to land at Tamatave. This would mean that the capital would be threatened from both the west and the east.

The operation got underway just before daylight on 10 September 1942. The Vichy, having surrendered over 3,000 troops at Diego Suarez, was down to around 4,800 supported by sixteen artillery pieces and, by this stage, probably five aircraft. The assault on Majunga, known as Operation Stream, was spearheaded by the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and the East Lancashire Regiment. They landed ten miles to the north of the town. The South Lancashire’s and 5 Commando secured Majunga harbour. At dawn, Swordfish buzzed ominously over the port, although they made no attacks and there was no sign of French aircraft.

As soon as the port was in British hands the East African Rifles and the Marmon-Herrington Mark III armoured cars of the South Africans sped down the road. Although the distance to the capital was 270 miles, this was as the crow flies and the road route was more like 400 miles. It was important that they captured important bridges along the route. By 1600 hours on 10 September they had captured the first one, 99 miles inland. By dawn on 11 September they were approaching the second one, at a distance of 131 miles.

The French had tried to destroy the bridge, but all they had achieved was that the central span was sagging into the river and, at worse, part of the road was under 3 feet of water. As soon as they realized their mistake, at 0730 hours, Capitaine Baché, in a Potez 63-11, was sent to drop bombs to finish off the bridge. The attack was a failure.

The airfield at Majunga was now in British hands and elements of the air cover, including Lysanders, were brought down to begin operations. In the early hours of 12 September 1942 a pair of Marylands engaged Vichy French motor transport between the broken bridge at Betsiboka and Tananarive. One Maryland was hit by anti-aircraft fire, which killed the observer and knocked out one of the engines.

The French beyond the broken bridge set up a series of roadblocks. But it was not until 16 September that the advancing forces came up against serious opposition. They were trying to take a bridge over the Mamokomita River at Andriba when they ran into a company of Senegalese. The leading East African company, supported by armoured cars, 25-pdrs and mortars, took the position.

On 17 September Annet requested an armistice and a Maryland was sent to Ivato to pick up French negotiators. After discussions the French rejected the terms and they were flown back to Ivato on 18 September. Meanwhile, Tamatave surrendered after a threeminute bombardment. The 29th Brigade clambered ashore and now the race to capture Tananarive was on. For the East Africans and the South Africans progress was now relatively slow because the French had destroyed bridges and culverts, which meant that a great deal of engineering work had to be carried out.

At Tamatave a number of the South Lancashire’s had taken the opportunity to clamber on board a train that had just entered the station. They steamed fifty miles down the coast and captured Brickaville, which was on the coast road to Tananarive before it turned inland.

As the two competing columns of British and Commonwealth troops converged on the capital, Vichy French resistance began to stiffen. This meant that the air assets would once more be required. The Vichy French aircraft were all now based at Fianarantsoa, way to the south of the capital. Estimates vary, but the Groupe Aerien Mixte probably now amounted to a pair of Morane 406s, one Potez 63-11, perhaps two Potez 25TOEs, a Potez 29 and a Phrygane.

The latter aircraft was a French light aircraft, which was a highwing monoplane with a fixed undercarriage. The aircraft had first flown in October 1933 and had been built by Salmson, a French engineering company. Only twenty-five aircraft had been sold before the outbreak of the Second World War.

By 21 September the East Africans had closed to a strongly held Vichy position at Mahitsy. The position was held in depth on high ground. During the night of 21 September the positions were outflanked, but two days of fighting lay ahead before the French finally abandoned the positions. They were now only thirty miles from the capital, but the French had dug in around another strongpoint, at Ahidatrino. The French would not put up a fight because as a column of 22nd Brigade approached them on 23 September the bulk of the Vichy troops fled and a handful held on for half an hour before they, too, fell back. This meant that at 1700 hours on 23 September the East Africans and the South African armoured cars entered the capital. Meanwhile, on the other side of the island, covered by 1433 Flight’s Lysanders, the 29th Brigade advanced from Brickaville. They, too, arrived in the capital in time for a victory parade.

There was good news and bad news. The good news was that the French had left behind aerial photographs of all of their airfields on Madagascar. The bad news began with the French refusal to surrender. This was quickly followed by the realization that the bulk of the Vichy French troops still willing to fight had fled south towards Fianarantsoa. As Allied troops moved south to pursue them they discovered roadblocks. Across one short stretch of road there were twenty-nine stone walls, up to 18 feet across. On another half-mile stretch 800 trees had been chopped down.

Fianarantsoa was the only major centre of population left on Madagascar that was still in French hands, but it also was the home of what remained of the Vichy French Air Force.

On 25 September two South African Marylands dropped bombs on a Vichy-held fort just after dawn. They dropped sixteen 250 lb bombs on the Tananarive to Antisirabe road. There was a British loss during the day when a Fleet Air Arm Fulmar belonging to 795 Squadron went missing.

A single Morane 406, flown by Lieutenant Toulouse, was active between 28 and 30 September 1942. On the first two days he flew reconnaissance missions to the north of Antisirabe and on the final day he strafed vehicles leading the British advance.

A single Maryland was flown into Ivato to refuel and then sent on a reconnaissance mission to inspect Vichy landing grounds to the south of the capital. The results were negative.

The ground war continued with troops from Tanganyika entering Antisirabe on 2 October. South African troops had also landed at Tulear in the south-west of Madagascar. They were moving up towards the capital via Sakaraha. Another force had landed at Fort Dauphin in the far south-east of the island. The landings had not gone unobserved, however. Capitaine Baché, flying a Potez 25TOE, and a Morane 406 flown by Sergeant Chef du Coutrin, had buzzed the positions. Further reconnaissance was made by the Vichy on 3 October.

A number of aircraft were moved to Antisirabe and Ivato during the day of 3 October, in preparation for the last attacks. The Vichy Air Force got in the first blow when Sergeant Chef Largeau in a Morane 406 strafed Bren gun carriers near Antinchi on 6 October. The British now responded by making offensive sweeps across all the known airfields on 7 October. A pair of Fulmars spotted a Potez 63-11 airborne, but the French pilot evaded them.

By now, the French aircraft had been pulled back to their new operational base at Ihosy. Aerial reconnaissance by a pair of Marylands, who also dropped bombs on the hangar there, confirmed that this was the main French aircraft concentration.

On 8 October three Beauforts came in to bomb Ihosy airfield. The French had been canny, however, and had positioned their aircraft in the bushes up to a mile away from the airfield itself. The Beaufort crews confirmed that they had seen three Potez 25TOEs, a Morane 406 and a Potez 63-11. The Beauforts strafed the targets, reporting that the Morane had been partially set on fire. They then radioed the positions to the incoming South African Marylands. The photographic evidence confirmed the situation; a Potez 25TOE had been set on fire and the Morane had certainly been hit. But the French had acted swiftly after the Beaufort attack and had moved the aircraft around to try and hide them even further. Another bombing attack wrecked one of the Potez 25TOEs. More attacks came in, which ultimately saw a Potez 29 and a Potez 63-11 also destroyed. Incredibly, the Morane was still intact and Sergeant Chef Largeau flew a reconnaissance mission on 12 October.

On the same day four Beauforts bombed the airfield again and three days later Marylands attacked Vichy positions to the south of Ambositra. The Vichy positions here were bombarded and the enemy troops finally surrendered as Commonwealth troops closed in.

The artillery barrage had broken up the positions and the Vichy forces had been attacked in the rear by the King’s African Rifles. The commander of the French troops, Colonel Metras, and his headquarters also fell into British hands. By this stage the Vichy forces were down to around six depleted companies. They fell back towards Fianarantsoa.

At dawn on 20 October the Vichy forces suffered a frontal attack by Tanganyika infantry. At the same time South African armoured cars and Kenyan infantry worked around their flanks and captured 200 prisoners.

Incredibly, the Morane 406 was still operational and it had even launched strafing attacks on South African troops. However, by 21 October it was just the Salmson Phrygane that was left serviceable and it made its final sortie on 22 October, piloted by Capitaine Baché. The airfield at Ihosy was still being bombed as a precautionary measure, as were the final French ground force positions to the north of Alakamisy.

The armistice was finally signed in the early hours of 6 November 1942 and the former Vichy governor was flown to Tamatave. The French had finally surrendered some forty-two days after the capture of the capital. The ceasefire came into force at one minute past midnight on 6 November.

However, this would not be the last time that the Vichy Air Force would be in action against their former allies. On Sunday 8 November 1942 Operation Torch was launched, as the Anglo-American forces landed in French Algeria and Morocco.