By 5 April all of the vessels involved in the operation had reached Freetown in Sierra Leone. Only a handful of the men actually knew their destination. Once they were back out to sea the men were briefed; they were to capture Diego Suarez harbour and D-Day was set for 0400 hours on 5 May.

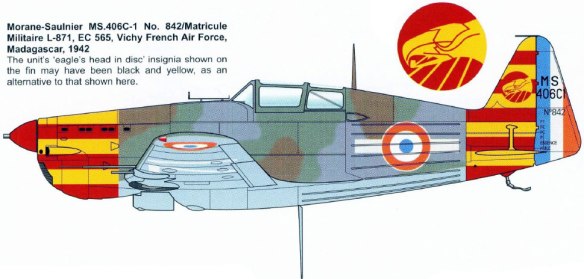

The French had managed with a handful of Potez 25TOE army cooperation biplanes on Madagascar until the middle of 1941. In January 1941 the Vichy French had decided to create Escadrille 565, which was supposed to have received Morane 406 fighters. As it was, nothing had happened until the end of July 1941. Some thirteen pilots had already been sent to Arrachart airfield, some seven miles to the south of Diego Suarez. They were under the command of Capitaine Leonetti. When the men arrived without their aircraft they found that the airfield was in a dreadful mess. All they could do was to try to sort the airfield out and fly some training sorties in the Potez 25TOEs. On 23 July seven Potez 63-11s arrived on board SS Bangkok. They were sent to Ivato-Tananarive, which was in the centre of the island.

By October 1941 the first of the Morane 406s arrived and it was decided in February 1942 to put all of the Moranes and the Potez 63-11s under a unified command. Although figures are sketchy, it does appear that around twenty Moranes were sent to Madagascar. Ground troops on Madagascar amounted to something in the region of 8,000. The vast majority of them were native Malagasy, although there were some Senegalese and French troops. The garrison of Diego Suarez was around 3,000, supported by mule-drawn 75 mm guns, five coastal batteries, a handful of anti-tank guns and some anti-aircraft weapons.

The approach to Diego Suarez harbour was perilous; not only was it covered by the coastal battery, which was in telephone contact with an observation post, but also there were reefs, shoals and mines. There were also some two miles of pillboxes and trenches built around the dockyards. There was a pair of redoubts made of concrete, known as Forts Caimans and Bellevue.

In truth, however, these defences, known as the Joffre Line, were in a serious state of disrepair. Whole stretches of the trench system were covered in vegetation, but the French set about putting them back in order, as well as impressing civilians to build an anti-tank ditch.

The first part of the British force left Durban on 25 April 1942, consisting of the cruiser HMS Devonshire, and a pair of destroyers, along with some corvettes and minesweepers. On 28 April the assault ships, along with the cruiser HMS Hermione, the battleship HMS Ramilles and the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious and six destroyers, departed.

The fleet passed to the west of Madagascar and on 3 May joined up with HMS Indomitable, along with two escorting destroyers. It was hoped that the two air groups would be sufficient to eliminate the Vichy French Air Force and to supply sufficient support for the ground troops. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy Eastern Fleet, including the aircraft carrier, HMS Formidable, was patrolling the Indian Ocean just in case the Japanese chose to intervene. By midday on 4 May, the spearhead of the vessels involved in the operation rounded Cap d’Amer, on the northern tip of Madagascar. It was so far so good; the French had no idea that the invasion force had arrived.

The first wave of assault craft hit the beaches at around dawn on 5 May. The lead elements consisted of 5 Commando and the East Lancashire’s. Surprise was nearly ruined when one of the minesweepers exploded two mines. Incredibly, they caught the French, literally, asleep. The gunners that were supposed to be manning the coastal defences were rounded up. Only one of the French officers resisted, but he was shot through the forehead. Thus, the battery at Courrier was taken with, literally, one shot.

Just before dawn HMS Illustrious launched three strikes, each consisting of six Swordfish, to attack shipping in Diego Suarez bay. Albacores, meanwhile, headed to bomb Arrachart airfield. The beaches and the bombing attacks were covered by fighters. The Swordfish sank the armed merchant cruiser Bougainville and then the submarine Bévéziers. One of the aircraft, flown by Lieutenant Robert Everett, RN, was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. He and his crew were taken prisoner. Everett had been dropping leaflets in French in order to encourage the Vichy troops to surrender and to justify Britain’s actions against Madagascar.

As the Albacores and Martlets hit Arrachart airfield they had caught the majority of the French aircraft napping. Five of the Morane 406s were destroyed and another two damaged, as was a pair of the Potez 63-11s. The French detachment commander, Lieutenant Rossigneux, was killed in the attack. At a stroke, the Vichy air strength on the island had been reduced by 25 per cent. As soon as the British landings became known, a number of Potez 63-11s and Morane 406s were hastily flown up to Anivorano, some fifty miles to the south of Diego Suarez.

Meanwhile, on the ground advanced units of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers had come across a French officer in a car. He was deliberately not blindfolded, so that he could see the full strength of the invasion force. Subsequently, the same officer would be sent back to his own headquarters to deliver a message from the British, calling on the French to surrender. However, the Frenchman had seen everything he needed; it was clear exactly where the British were heading and this gave the Vichy commander on the island, Annet, enough time to get his mobile reserves and anti-tank guns into the Joffre Line. By 1115 hours French troops were firing back, holding a ridge line. But this was forced by the British and by 1500 hours the French had fallen back to the Joffre Line.

A vessel that had been missed by the British in Diego Suarez bay earlier, the sloop D’Entrecasteaux, was finished off by four Swordfish. Navy Martlets and Fulmars were flown on reconnaissance sorties. The only sign of the French Air Force had taken place at around 1700 hours, when a pair of Morane 406s had strafed the beaches of Courrier Bay. The aircraft flown by Sergeant Ehret never returned and his fate is unclear. The French lost another aircraft that day, again under strange circumstances. It was a Potez 63-11 flown by Lieutenant Schlienger and it is possible that it was shot down by British ground fire.

The French did launch an attack at around 0600 hours on 6 May 1942, when three Potez 63-11s attempted to attack the beach landing points. They were intercepted by Martlets of 881 Squadron. In the ensuing fight Lieutenant Bird and Sub-Lieutenant J. Waller shot one of them down and a second was claimed by Lieutenant C.C. Tomkinson. Albacores were used to bomb French defences, whilst Sub-Lieutenant F.H. Alexander, in his Swordfish, managed to sink the French submarine Le Heros, with depth charges. By the early hours of 7 May the residual French resistance before the Joffre Line had been worn down.

The plan was now to strike east, from Ambararata towards Antsirane. In fact, the British force had achieved an eighteen-mile advance in some twenty-four hours. It was decided to launch a diversionary attack by the fifty or so Marines, commanded by Captain Martin Price, on board HMS Ramillies. HMS Anthony circled around the northern tip of Madagascar and delivered the men for their diversionary attack.

HMS Anthony approached at high speed, coming under fire from the shore batteries. The destroyer landed fifty Royal Marines, under the command of Captain Martin Price, RM, at around 2000 on May 6 1942. The men scrambled onto the quay at Antsirane and stormed the French army barracks. They also took the arsenal and scooped 500 prisoners. HMS Anthony then left the harbour and crashed through the boom at the harbour entrance. At that point a French searchlight found her, but a salvo from HMS Devonshire wrecked the searchlight and enabled the vessel to return to the anchorage. It took twenty-four rounds of 15-inch shells from HMS Ramillies to persuade the gun batteries in the forts on the Orangia Peninsular to surrender on the afternoon of May 6. By this time British and allied forces had managed to secure their first objectives.

At the same time, a determined attack was made on the Joffre Line. The two leading battalions, the 6th Seaforth Highlanders and the 2nd Northamptons, took up start positions barely 1,200 yards from French trenches. Behind them were the Royal Scots Fusiliers and the 2nd Royal Welsh Fusiliers. The attack was timed to coincide with the landing of the Commandos. HMS Anthony passed the entrance batteries unharmed and came along the quayside at 2200 hours. She dropped off the Marines and then went back out to sea. It was half an hour before the British infantry had got on their feet and had begun to storm the main French defence lines. With a combination of grenades and bayonet attacks all of the strong points were taken and before dawn on 7 May 1942 British troops were well established in Antsirane.

The battle for Madagascar was by no means over. Overhead, Martlets of 888 Squadron encountered, for the first and only time, French fighters. Three Morane 406s flown by Capitaine Leonetti, Capitaine Bernache-Assollant and Lieutenant Laurent were spotted on a reconnaissance mission. One of the Martlets was shot down by Leonetti, whilst Sub-Lieutenant J.A. Lyon claimed that he had shot down one of the French fighters, but he was probably mistaken. A second group of Martlets dived down to assist. Lieutenant Tomkinson was to claim one Morane 406 and Sub-Lieutenant (A) Waller claimed a second. The pair of them then attacked a third French fighter. It is clear that all three French aircraft were lost, with one of the pilots killed, one wounded and another injured as he hit the ground having baled out. The operation, so far, had claimed twelve Morane 406s, and perhaps five Potez 63-11s, out of a comparatively small French force.

By 1040 hours on 7 May, British warships opened up a barrage on Diego Suarez. British minesweepers began clearing the channel into the harbour and by 1700 hours the Royal Navy was also in the harbour. The French were already negotiating surrender terms.

But this was only a part of Madagascar. In fact, the capture of the capital had changed very little. Undoubtedly, the momentum was with the British, but the French would drag their feet, hoping that the rainy season would begin and buy them time. So far, the Fleet Air Arm had completed over 300 sorties. There was now an opportunity to reorganize the air components in Madagascar. Finally, 20 SAAF Squadron could come in to Madagascar as had been planned.

The British had already decided to re-launch the Madagascar campaign and to divert assets in order to achieve this. De Gaulle had even proposed to land Free French on the island and Annet had contacted the Vichy Government to ask for more assistance, particularly in the shape of aircraft. But the nearest Vichy base was French Somaliland and the best that the limited number of French aircraft there could achieve was nuisance raids against the British. This would only enrage Britain further and bring about the immediate occupation of French Somaliland. As a consequence, Annet quickly realized that they would be on their own; there would be no reinforcement.

In the period June to August 1942, 20 SAAF Squadron carried out comprehensive photographic reconnaissance missions to build up a picture of the interior of Madagascar, in preparation for a new offensive. On one occasion, after one of the Marylands was shot down by Vichy French anti-aircraft fire, French troops rushed to capture the crew. As they arrived on the scene they were brought under fire from the Vickers machine gun in the dorsal turret of the aircraft. The South African crew captured the Vichy patrol, marched their prisoners to the coast and rendezvoused with a British destroyer.

By August it was clear that the probable French air strength on Madagascar was down to four Morane 406s and three Potez 63-11s.