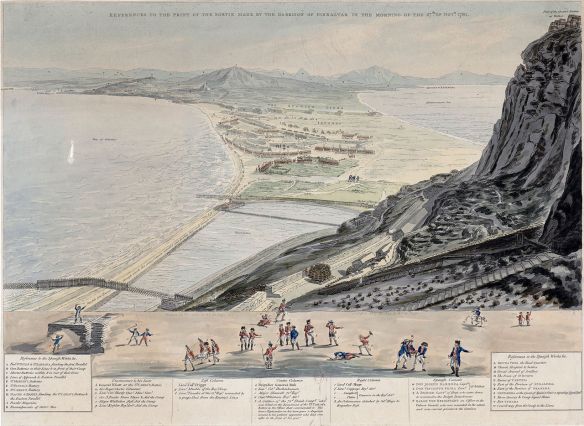

View of the sortie from above the Prince’s Lines.

The French and Spanish found it was impossible to starve the garrison out. They therefore resolved to make further attacks by land and sea and assembled a large army and fleet to carry this out. But on 27 November 1781, the night before they were to launch the grand attack, half the British garrison filed silently out of their defence works and made a surprise sortie.

The sortie routed the whole body of the besieging infantry in the trenches, set their batteries on fire, blew up and spiked their cannon, destroyed their entrenchments, and killed or took prisoner a large number of the Spaniards. The British did damage to the extent of two million pounds to the besiegers’ stores and equipment that night. Spanish losses were over 200 and Governor Eliott claimed many were ‘killed on the spot’ because of the surprise. As the Spanish recovered and prepared to launch a counter-attack, the British withdrew back inside their fortifications.

This reverse postponed the grand assault on Gibraltar for some time. Still, the Spaniards closely maintained the siege.

A contemporary drawing by Captain John Spilsbury of what he calls the “Junk Ships” lined up off King’s Bastion.

On 13 September 1782 the Bourbon allies launched their great attack; 5190 fighting men both French and Spanish aboard ten of the newly engineered ‘floating batteries’ with 138 heavy guns, as well as 18 ships of the line, 40 Spanish gunboats and 20 bomb-vessels with a total of 30,000 sailors and marines. They were supported by 86 land guns and 35,000 Spanish and French troops (7,000–8,000 French) on land intending to assault the fortifications once they had been demolished. An ‘army’ of over 80,000 spectators thronged the adjacent hills over the Spanish border, among them the highest families in the land, assembled to see the fortress beaten to powder and ‘the British flag trailed in the dust’. The 138 guns opened fire from floating batteries in the Bay and the 86 guns on the land side, directed on the fortifications after weeks of preparatory artillery fire. But the garrison replied with red-hot shot to set fire to and sink the attacker’s floating batteries and warships in the Bay. In that great conflict, the British destroyed three of the floating batteries, which blew up as the ‘red-hot shot’ did its job. The other seven batteries were scuttled by the Spanish because they were too heavily damaged to continue the fight. In addition 719 men on board the ships (many of whom drowned) were casualties.

A projected assault upon Gibraltar.

On 4 July 1776, as all the world knows, the British colonies of North America declared their independence. The conflict that had begun as a dispute over British colonial affairs had developed in just two years into a crisis after which the world would never be the same. In March 1778 France joined the fray on America’s side, Louis XVI–who had succeeded his grandfather four years before–doing everything he could to persuade Charles III of Spain to follow his example. Charles was initially doubtful. His last-minute participation in the Seven Years’ War had proved catastrophic; more recently, an expedition against the Algerian pirates in 1774 had been less of a disaster than a disgrace. He desperately needed a few military successes. Moreover, he himself possessed vast colonies in the New World–did he really want to encourage revolution among them? Finally, he was angry with Louis. By the terms of the Family Compact the French King should have consulted him before entering into his American alliance; now he was calling on Spain to join him in the name of that very same pact. Charles therefore offered his services as mediator between the two sides. Britain, he proposed, should suspend hostilities for a year; during that time the American colonies were to be treated as independent and there would be a peace conference in Madrid, in which the American representatives would be on an equal footing with those of Britain. The price of this mediation would, it need hardly be said, be Gibraltar.

The British government, not altogether surprisingly, turned him down flat. His proposal, it declared, ‘seemed to proceed on every principle which had been disclaimed, and to contain every term which had been rejected’. Faced with this, in June 1779 Charles too declared war. For the future of Britain’s American colonies, he cared not a jot, but Gibraltar and Minorca were prizes worth the winning. The question was, how could they best be won? He considered no less than sixty-nine separate suggestions. One of the first–and perhaps one of the best–was an invasion of England. He and the French together could easily have mustered both a fleet large enough to overwhelm the Royal Navy in the Channel and an army capable of dealing with the relatively few British forces who were not fighting in America. But the idea did not ultimately appeal: Charles preferred something more direct. He decided to put Gibraltar under siege.

That siege began on 11 July 1779, when the newly-arrived Spanish commander, Martín Alvarez de Sotomayor, fired a single shot from Fort St Barbara across the border. The British General Sir William Green replied–it was the first time that his guns had been fired in anger for over half a century–and kept up the barrage for some twenty-four hours. Over the next two months the besiegers dug themselves in, built gun emplacements and provided themselves with shelter for the coming winter, while their forces steadily gathered in strength: by the end of October they numbered well over 14,000. The British garrison, by contrast, amounted to some 4,000 officers and men, plus 1,300 Hanoverians; the Governor, General George Augustus Eliott, also had to reckon with some 1,500 soldiers’ wives and children and a local population of another 2,000. Food, he saw, would be a serious problem. Since the Spanish blockade was not yet total, he encouraged all who felt like it to leave the Rock as soon as possible. A number of Jews and Genoese agreed to do so, and made their way in small boats to Portugal or the Barbary Coast; the remainder were obliged to stay until the arrival of a convoy from Britain–if one got through.

From the start, Green set a stern example to his men. To save food–and to augment its supply–he had one of his own horses shot. To calculate minimum food needs, he lived for a week on four ounces of rice a day. And he stood no nonsense: one of his officers, Captain John Spilsbury, wrote in his diary:

October 3. It seems one 58th was overheard saying that if the Spaniards came, damn him that he would not join them: the Governor said he must be mad and ordered his head to be shaved, to be blistered, bled and sent to the Provost on bread and water, wear a tight waistcoat and be prayed for in church.

It was not until 16 January 1780 that the good news finally came. A fleet of twenty-one ships under Admiral Sir George Rodney had attacked a squadron of ten Spanish vessels off Cape St Vincent, destroying two, taking four and putting the rest to flight. In a separate engagement he had also captured fifteen merchantmen. The blockade was broken; provisions and supplies were landed, together with 1,000 Highlanders; the wives and children of most of the rank and file were carried away to safety. There was only one cause for distress: the relief had brought no wine or rum. As the Governor pointed out, ‘The want of strong liquor will perhaps be more severely felt by the Soldier than the curtailing of a small part of his provisions, and possibly might affect his health, from the alteration of a habit he is accustomed to.’

Meanwhile, the siege was by no means over. By early spring a savage epidemic of smallpox broke out on the Rock and was soon taking a heavy toll. The Spanish blockade was tightened again, and as the year dragged on provisions once more grew desperately short. The Spaniards meanwhile were quiescent, and the defenders had to contend with another serious threat to their morale: boredom.

The new year of 1781 began badly. On 11 January two Moorish galleys were seen approaching under a flag of truce. They carried the British consul in Tangier and his wife, together with about 130 British subjects, all expelled from Morocco after its Sultan had leased Tangier and Tetouan to Spain. This meant that no more supplies could be expected from Barbary, and that Eliott had another 130 mouths to feed. Yet somehow he managed to struggle on until at last, at daybreak on 12 April, Admiral George Darby brought his fleet into the Bay of Algeciras. At first it was obscured by a mist, but, wrote another eyewitness, Captain John Drinkwater:

As the sun became more powerful the fog gradually rose, like the curtain of a vast theatre, discovering to the anxious garrison one of the most beautiful and pleasing scenes it is possible to conceive. The convoy, consisting of near a hundred vessels, were in a compact body, led by several men-of-war; their sails just enough filled for steerage, whilst the majority of the line-of-battle ships lay-to under the Barbara shore, having orders not to enter the bay lest the enemy should molest them with their fire-ships. The ecstasies of the inhabitants at this grand and exhilarating sight are not to be described. Their expressions of joy far exceeded their former exultations.

It was a quarter to eleven when the first vessel dropped anchor, and at that very moment the Spanish emplacements opened fire. Instantly, rejoicing changed to astonishment, astonishment to panic. The threat of bombardment had existed since the beginning of the siege, but for eighteen months there had been nothing but an occasional desultory shot, and the people had largely forgotten the danger. Now, suddenly, the horror was upon them–a hail of shells and cannonballs, spreading devastation and havoc through the little town. In the early afternoon it slackened, then stopped altogether–even with the future of Gibraltar at stake, the Spaniards were not going to forgo their siesta–but it started again at five o’clock that evening and continued throughout the night.

The next morning revealed a town in ruins–and also, through the crumbling walls of the houses, the storerooms of the traders, many of them bursting with secret provisions of every kind which they had deliberately withheld in order to dole them out item by item for exorbitant prices. Inevitably there was wholesale looting, particularly from the wine merchants. On Sunday morning, 15 April, Captain Spilsbury noted with distaste that ‘such a scene of drunkenness, debauchery and destruction was hardly ever seen before.’ In an attempt to restore order, a group of officers armed with axes made a round of the provision stores, staving in barrels until the streets ran with wine and brandy.

Through it all, the unloading went on at the rate of ten ships a day. Admiral Darby had orders to sail with the first favourable wind, and the victuallers had no wish to be left behind. It was soon discovered, however, that the government in England had forgotten to send one all-important commodity: gunpowder. Eliott had no alternative but to beg as much as possible from Admiral Darby, who was happy to oblige with 2,280 barrels. ‘It is,’ he wrote, ‘the noble defence you are preparing to make which has induced me to stretch this supply to the utmost…Happy am I in doing everything in my power for the Service of the Garrison on which are fixed the Eyes of the whole World.’

On 20 April the Admiral was ready to sail. Whereas on the outward journey the vessels had been loaded to the gunwales with stores, the freight they carried on their return was largely human: most of the officers’ wives and children, and virtually all the remaining Jews and Genoese, many of whom had paid dearly for their places on board. They probably amounted to half the total population of the Rock.

May 7th 1781.

My Lord,

I must not conceal from you the scandalous irregularity of the British Regiments composing this Garrison ever since the Enemy opened his Batteries; except Rapes and Murders, there is no one crime but what they have been repeatedly guilty of and that in the most daring manner…Things are so bad that not a sentinel at his post but will connive at and assist in robbing even The King’s Stores under his charge…

This letter, written by Eliott to Lord Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of the British armed forces, makes it all too clear that the town of Gibraltar, already largely destroyed, was now being systematically sacked by its supposed defenders. The Governor took firm measures against them: the artificers Samuel Whitaker and Simon Pratts were hanged on 30 May, and William Rolls of the 58th Regiment was given a thousand lashes, administered in public on the South Parade. Even without legal retribution, however, the looters were still risking their lives: the bombardment continued without remission. The several diaries and logbooks take a gruesome delight in describing the casualties: ‘Two men killed one of which was in the office easing Nature when a Ball took off his head and left His Body, the only remains to finish Nature’s cause.’ Nor was all the damage done by the shore batteries; there were now quantities of small Spanish gunboats lying off the Rock and keeping up a constant barrage at anything that moved. They were particularly dangerous at night; Mrs Catherine Upton, wife of one of the ensigns, described how ‘a woman, whose tent was a little below mine, was cut in two as she was drawing on her stockings.’ ‘These infernal spit-fires,’ she added, ‘can attack any quarter of the Garrison as they please.’ On 23 May, her diary continued,

at about one o’clock in the morning, our old disturbers the gun-boats began to fire upon us. I wrapped a blanket about myself and the children, and ran to the side of a rock…Mrs Tourale, a handsome and agreeable lady, was blown almost to atoms! Nothing was found of her but one arm. Her brother who sat by her, and his clerk, both shared the same fate.

The good news was that the besiegers had abandoned the blockade. It had not anyway been singularly successful, and now that it had failed to prevent the delivery of enough stores and provisions for the next two years there seemed little point in going on. Communications with the outside world were restored, and food and drink were once again plentiful, but the siege went on regardless.

The summer heat, too–the worst that Captain Spilsbury had experienced in his twelve years in Gibraltar–began to take its toll on both sides. By the end of July the Spaniards were firing only three shots a day, so regularly that the garrison began to refer to them as the Father, Son and Holy Ghost. (A major explosion in their powder magazine on 9 June may have been partly responsible.) Among the besieged, tempers grew short. On 22 July a major and the adjutant of the 72nd fought a duel with three pistols each; fortunately they missed with all six. A few days later the garrison watched tight-lipped while a Franco-Spanish invasion fleet sailed eastward through the straits bound for Minorca. There was no doubt that the island’s Lieutenant-Governor, General James Murray, would need all the help he could get.

With the approach of autumn, the atmosphere on the Rock, both physical and social, improved. In October, however, the defenders saw to their anxiety that the Spaniards were building two new parallel batteries along the isthmus, uncomfortably close to the boundary and protected by huge banks of sand which were virtually impenetrable by the British guns. It was plain that an all-out assault was intended.

And so, on 27 November at a quarter to three in the morning, over 2,000 men and 100 sailors–about a third of the whole garrison–led by a detachment of Hanoverian grenadiers, filed in silence out of the fortress, through the devastated town and out on to the isthmus. The Governor–he was to turn sixty-five on Christmas Day–was among them. His absence from the garrison was distinctly improper, but he had been unable to resist. There was some counter-fire, but surprisingly little; after a few token shots the Spaniards, taken entirely by surprise, fled before the invaders. One by one the Spanish emplacements were destroyed, their powder magazines ignited. By five o’clock all was over and the force returned, with eighteen prisoners, to the Rock. The operation had been a complete success. Equally important, perhaps, was the effect on the garrison’s morale. The looting stopped as if by magic. The total casualties were five killed, twenty-five wounded; one of the Highlanders, it was reported, had lost his kilt.

While Gibraltar was holding its own, Minorca was fighting for its life. In early August 8,000 Spanish troops had landed on the island. They were commanded by the sexagenarian Duc de Crillon, who had joined the Spanish army when Spain entered the Seven Years’ War. Against such a force Governor Murray’s 2,700 men, many of whom were sick, could only retreat to Fort St Philip, where Crillon sent the Governor a message, asking him frankly how much he would charge for an immediate surrender. Murray rejected the offer with indignation, and the siege began.

Despite the arrival in September of 4,000 French troops to swell the Spanish ranks, Crillon at first made little progress. At the end of the year, however, scurvy appeared in the fortress, and within weeks created havoc among the British ranks. There was nowhere where fruit or vegetables could be grown, nor were there any friendly ports nearby from which they could possibly be infiltrated through the Spanish blockade. The only hope was a relief expedition from England, but none came. Within a month many of the men had to be carried to their posts; at a roll-call on 1 February 1782 only 760 of the 2,700 were able to answer, and three days later 100 of those were in the infirmary. On 5 February, after a heroic resistance of five and a half months, Murray surrendered. Minorca was Spanish again.

The news did not reach Gibraltar until 1 March, when a Spanish officer appeared under a flag of truce with a detailed report. It was received philosophically, having long been expected, and seems to have had little long-term effect on morale. Winter had been grim enough–the Rock too had seen a serious outbreak of scurvy, and by 20 December over 600 men had been hospitalised–but early in February three vessels had arrived from Portugal loaded with oranges and lemons, and the beneficial effect had been immediate. The weather too was improving fast, and early in March HMS Vernon sailed in with two frigates and four transports carrying welcome reinforcements, including ten gunboats and a whole new regiment. Thanks to these, the garrison was able to face the coming year with confidence and hope.

What its members did not realise was that while they had been defending their Rock the outside world had changed. The American War of Independence was over; Europe, as well as America, wanted peace. Only Spain held out. Charles III had entered the war for one reason only: to recover Minorca and Gibraltar. Minorca was now his, but Gibraltar, for all its obvious proximity to his kingdom, seemed as far away as ever. In France, Louis XVI and his government cared little for Gibraltar; on the other hand, by the secret Convention of Aranjuez which they had been incautious enough to sign in 1779, they were bound to continue fighting until Spain had recovered it. With the greatest reluctance, therefore, they prepared to show her how the job should be done.

On 1 April 1782 a mysterious figure named Chicardo arrived in a small boat from Portugal with a report that the Spaniards had commandeered twelve ships at Cadiz, and that they were lining them with cork, oakum and old rope cables for use against Gibraltar. Ten days later came further confirmation: these ships were to be used as floating batteries under the direction of a celebrated French military engineer. They appeared in the harbour of Algeciras on 9 May: large Indiamen in such an advanced state of dilapidation that, as one observer reported, ‘most people think they are more fit for fire-wood than attacking a fortress.’ By this time the harbour and roadstead were filling fast, as more Spanish ships arrived almost daily. Spring turned to a sweltering summer, and the defenders had little to do but watch, and try to interpret, the frantic activity that continued in the Spanish lines. On 17 June they were horrified to witness the arrival of a fleet of sixty transports, escorted by three French frigates; here was the first detachment of Louis’s army, estimated to be not less than 5,000 strong. Then, just five days later and quite without warning, the bombardment stopped. After well over a year of unremitting thunder, the sudden silence was distinctly unnerving. Only later was its significance understood: it signalled the succession of the Duc de Crillon, fresh from his triumph at Minorca, to the command of the combined armies of France and Spain.

On 14 July a Spanish deserter–presumably fleeing from justice–slipped through the lines and presented himself to the sentries. He too had much of interest to report. The floating batteries–there were now ten of them–were being roofed and would be ready by the end of August. The army before Gibraltar now consisted of thirty-seven battalions of Spanish and eight of French infantry, two battalions of Spanish and four companies of French artillery, and several companies of dragoons and cavalry: a total of some 28,000 men. The good news was that there was much discontent, and almost daily desertions. Ten days later, on the 25th, two ships arrived from Leghorn bringing a certain Signor Leonetti, a nephew of Pasquale Paoli, who had with him two Corsican officers, a chaplain and sixty-eight volunteers. They also brought the welcome news of Admiral Rodney’s victory over the French in the West Indies at the Battle of the Saints. That same afternoon the Governor ordered a feu de joie to be fired by the heavy ordnance at one o’clock, and by the riflemen of the various regiments at six: ‘Three cheers when the firing is finished, to begin on the right, and pass along in the same manner as the firing did.’ The French and Spaniards, watching from below and confident that the Rock would soon be theirs, must have been confirmed in their long-held opinion that all the English were mad.