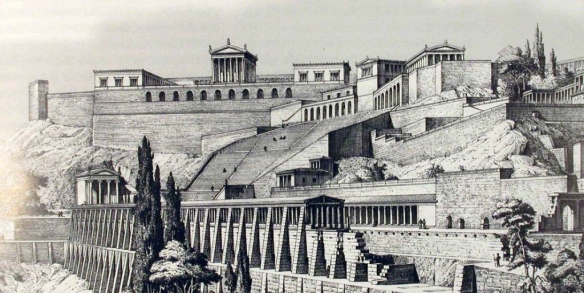

Reconstruction of ancient Pergamon.

Ancient Rhodes.

Not long before the battle of Pydna, at the time they had made their alliance, Perseus and Genthius had sent an embassy to the Rhodians, inviting them to join their anti-Roman coalition. The attempt was certainly worthwhile: the Rhodians were divided on the question whether their interests were best served by siding with Rome, or with Perseus, or by trying to stay neutral. But they were all agreed that their commercial interests demanded peace, so they told Perseus’ envoys that they would be sending a mission to Rome to try to bring an end to the war.

It must have seemed to the Rhodians that they had negotiated a tricky situation rather cleverly, but it all went badly wrong for them. Their peace ambassadors did not reach Paullus in the field until his victory was imminent, or secure an audience with the Senate until after news of Pydna had reached Rome. The Romans, already irritated by the Rhodians’ failure to supply them with the full contingent of forty ships they had promised, saw further signs of insincerity, and accused them of not really seeking peace, but wanting only to save Perseus; if they had really wanted peace, they would have tried to negotiate it when Perseus was doing well, not when he was doing badly. But, in fact, Perseus had been doing well when the Rhodians came to their decision; it was just that his fall had been very rapid.

At the same time as approaching Rhodes, Perseus and Genthius also sent embassies to Antiochus IV and Eumenes. They pointed out that the Romans had consistently pitted one monarch against another, and argued that if Macedon fell, the kings of Asia Minor would be Rome’s next targets. It would be in their interests, then, either to mediate an end to the war, or to join them against the Romans. But both Eumenes and Antiochus, for their own reasons, said no. Antiochus was involved in the Sixth Syrian War against Ptolemy VI, and hoped to complete his conquest of Egypt while Rome was distracted by the war with Perseus. In this he would be thwarted, as we saw in the Prelude: Rome was not so distracted that it did not send Gaius Popillius Laenas to wield the threat of Roman repercussions and bring the war to an end in 168.

For his part, Eumenes said no just because of his long hostility toward Macedon and friendship with Rome. He still felt himself to be riding high in the Romans’ favor, but in fact his position was less sure than he thought, and his enemies in Rome seized this opportunity to slander him. It was said that, rather than rejecting Perseus’ approach, he had prevaricated, saying that he would abandon the Roman cause and, depending on how much money he received from Perseus, either remain neutral (cost: 1,000 talents) or try to negotiate peace (cost: 1,500 talents). Gradually, over the months following Pydna, Eumenes lost the favor of the Senate.

Having caught wind of this, Eumenes went in person to Rome in the winter of 167–166 to protest, but he was brushed off with the pretense that the Senate would no longer receive kings in Rome. What had Eumenes done wrong? He seems to have been consistently loyal. In fact, whereas before he had been one of the main beneficiaries of Rome’s policy of balancing powers, now he became its victim. The Romans had decided to weaken Rhodes, and so they could not leave Eumenes strong. And Eumenes had recently been showing signs of independence. In 175, for instance, he had helped to place Antiochus IV on the Syrian throne, but the Romans wanted no king-makers in the east apart from themselves.

It was the beginning of the end for Eumenes and, in a repetition of their tactics with Perseus and Demetrius, the Romans openly began to favor his brother Attalus. Tempted at first, Attalus asked for Aenus and Maronea as his own personal domain, and the Senate agreed. But later, when Attalus turned against the scheme, the Senate declared the cities free and autonomous, and lost interest in this kind of direct interference in Pergamene affairs, since Eumenes was behaving himself. Prusias of Bithynia also asked to be rewarded with extra territory, which was refused, despite the fact that he, a king in his own right, abased himself before the senators.

Rhodes was treated just as harshly. There were even those in Rome who thought that war should be declared against the island state while there was still a Roman army in the east. They were an ineffective minority, and were famously opposed by Cato the Censor on both moral and pragmatic grounds, but it still shows how bad things had got. Immediately after the war, Gaius Popillius Laenas stopped off in Rhodes on his way to Alexandria to put an end to the Sixth Syrian War, and, in a ghastly attempt to assuage Rome’s hostility, the Rhodians voted to put to death the leaders of the pro-Macedonian faction, as a way of demonstrating their loyalty to Rome. And so they did—those who did not kill themselves first.

Along with every other state in the Greek world, the Rhodians sent emissaries to Rome to offer their congratulations on the victory at Pydna, but they were refused an audience with the Senate, and insultingly denied even hospitality, on the grounds that they were no friends of Rome. The Rhodian envoys took a leaf out of Prusias’s book and prostrated themselves before the Senate, but it was no use. They were punished by having almost all the territory they had gained at the end of the Syrian–Aetolian War taken from them.

The Rhodians were further damaged, financially, by the Romans’ turning the island of Delos into a free port, under Athenian supervision. The first reasons for this move were commercial rather than political; it was designed not so much to undermine Rhodes as to facilitate Mediterranean trade in general, especially in slaves (Delos rapidly became the center of the slave-trade). Nevertheless, it did seriously deplete Rhodian revenues, by 87 percent, according to one Rhodian spokesman’s implausible figure. Rhodes retained its main source of income—brokering the eastern Mediterranean grain trade—because Delos did not have a good enough harbor for the big transport vessels; but, all the same, many traders would now bypass Rhodes and head for the more relaxed regime of Delos. And Rome’s hostility damaged the Rhodians’ standing in the wider world.

Athens also gained the island of Lemnos, and the farmland of destroyed Haliartus became an Athenian enclave in Boeotia. Athens was rewarded not just for its goodwill towards Rome in the war (an offer of troops and a supply of grain), but because it could safely be strengthened without becoming powerful enough to threaten the balance of power, which was now to be constituted out of a number of equally weak states, rather than a few strong ones, as at the end of the Syrian–Aetolian War.

The humiliation of Rhodes and Pergamum was designed to set an example—to show that Rome’s power was now unchallengeable, that it could humble great states without even bothering to go to war. After Pydna, as a way of regularizing their relations with Rome and learning where they stood, the Rhodians repeatedly asked for a formal treaty of alliance, but they were always turned down: the Romans now recognized no equals. It was only once that lesson had been learned, perhaps in 164, that the Romans granted them an alliance, and then it was an unequal treaty, containing the notorious clause about maintaining the greatness of Rome, and allowing Rome to continue to intervene in Rhodian affairs. Meanwhile, Eumenes learnt his lesson more quickly. The rebuff he had received was enough to teach him what behavior the Romans now expected of him, and he apparently found little difficulty in complying. Better that Pergamum should survive as it was than assert itself and be cut down.