Armagnacs

On another occasion seven of the group were sent on a secret night mission to Préaulx Abbey. They were led by Hallé’s Friar Tuck, one brother Jehan de Guilleville, a renegade monk from the abbey who was already a veteran kidnapper and robber. With the aid of a ladder stolen from a nearby cottage he scaled the abbey walls and then broke down the door to enable his men to enter. Guilleville informed the seven terrified monks they found inside that they would be held hostage until they obtained the release of one of their brethren, his friend, who was being held prisoner at Pont-Audemer. This time, however, the brigands had overreached themselves. They carried off their hostages into hiding in nearby woods but the alarm was raised and within a few hours they were rounded up and all but two, who escaped, were thrown into prison.

It would be easy to dismiss Hallé’s band as nothing more than a particularly vicious criminal gang. The only thing that gives one pause for thought is the formal initiation that each applicant was made to undergo before he was admitted. As Laurens Hue explained it, he was obliged to swear that he would serve Hallé loyally and well ‘and that he would do everything in his power to damage and injure the English and all [their] subjects’. Having promised to do this, he was then given a complete new suit of clothing, including a hat and shoes (possibly a uniform?), together with a sword, bow and quiverful of arrows. The initiates were allowed to keep half of everything they won.

Though there remains room for doubt, the telling argument would seem to be that Hallé’s activities, like those of most brigands then operating, did nothing to undermine English rule: despite the initiates’ oath, there were no attacks on English natives, on English officials or on the infrastructure which made their administration possible. His victims were all Norman civilians, of the same humble class as himself (Hallé was the son of a poor labourer), and many of them were his neighbours, whom he attacked in their own homes. When he was captured again Hallé could not ransom himself a second time because he was now in breach of his oath: he was therefore executed as a traitor, not because he was a guerrilla warrior.

There are occasional references to Englishmen being murdered by brigands in the records of the Norman chancery but for the most part it was ordinary villagers who, especially in the first two years after the invasion, attacked and killed English soldiers who ventured out alone or in twos or threes. Naturally, since they were seeking to justify the offence to obtain a pardon, the killers claimed that they were acting in self-defence or were provoked by violence against themselves or their neighbours. These excuses might not always have been true but there were many examples of English soldiers who did abuse their position to rob, steal and rape, despite the best efforts of the English authorities to prevent and punish such behaviour because it antagonised the local population.

What is perhaps most striking about the evidence of the chancery records is that most of the crimes were not concerned with national identity or political difference. Racially abusive terminology abounds: the English are usually referred to as the ‘Goddons’, or God-damns, an allusion to their habitual cursing. The stock character invariably swears ‘by Saint George’ and drinks ale: a riot broke out at Le Crotoy in 1432 when Breton mariners insulted some men from Dieppe by calling them ‘treacherous English dogs, Goddons full of ale’. Nevertheless, race was seldom the sole cause of crime. An English merchant living in Rouen was stabbed to death in a quarrel over payment for goods he had received; an over-zealous tax-collector was killed (and his receipts thrown into the sea) by an angry man who thought he had already paid enough; the Norman lieutenant of the bailli of Tancarville was killed in a public-house fracas when drinking with a man he had previously arrested for assault. These were not the actions of politically motivated freedom fighters but the unintended consequences of petty squabbles in daily life which are still the staple diet of courts today.

The true resistance was to be found elsewhere, among those prepared to risk their lives to regain territory for the dauphin, either as a civilian fifth column plotting to seize English-held towns and castles or in military service at a frontier garrison such as Mont-Saint-Michel or under a die-hard loyalist commander such as the Harcourts, Ambroise de Loré or Poton de Xaintrailles.

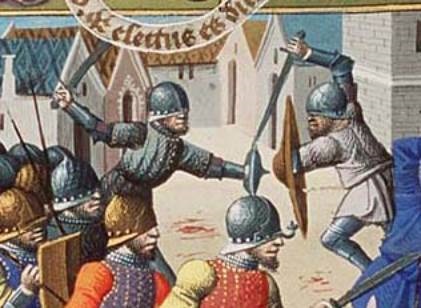

One could be forgiven for thinking that there was sometimes little to distinguish the activities of these Armagnac captains from simple brigandage. The raids of Jean d’Harcourt, count of Aumâle, on Saint-Lô in 1423 and Ambroise de Loré on Caen fair in 1431, for instance, caused terror and consternation because they struck unexpectedly and deep into the heart of Normandy, but in essence they were opportunist attacks whose principal objective was plunder and prisoners. (The same was also true, of course, of English raids into enemy territory.) To a peasant working in the fields perhaps the only observable difference between the smaller marauding groups of armed soldiers and brigand bands was that the former would ride with the banners of their captains displayed and wear the French badge rather than the red cross which Normans were required to bear. It was an important difference, however, as these identified the combatants as the legitimate enemy who were subject to, and protected by, the laws of war.

The French system of levying appâtis in times of war was also little more than legalised banditry. Appâtis were a form of protection money, paid every quarter in money and in kind, by the parishes of the surrounding countryside to their local garrison. The payments subsidised or even replaced the wages of the soldiers, who in return would refrain from seizing goods and persons without compensation. A parish paying appâtis might expect military protection from raids by other garrisons but, since the payments were theoretically voluntary, it laid itself open to the charge of being subject to that garrison and therefore a legitimate object of plunder by the enemy. For ordinary villagers trying to scrape a living by plying their trade or cultivating the fields and vineyards in frontier regions, it was simply a question of choosing the lesser of two evils: to be despoiled by the resident soldiers who would take an agreed sum or by marauding ones who might seize or destroy everything they had.

The plight of the inhabitants of L’Aigle was a case in point. They had been loyal English subjects since their submission on 13 October 1417, but the town had no walls and was regularly terrorised by the three Armagnac garrisons of Nogent-le-Rotrou, Ivry and Senonches, all less than forty miles away. Faced with the prospect of having to abandon their homes and farms, they decided to offer appâtis to the captain of the nearest, Senonches, but for just three months’ freedom from attack he would accept nothing less than 80 écus (£5833) and thirty-six war lances. The money was bad enough but to provide the enemy with arms was a capital offence. The parish priest who negotiated the deal was denounced to the English authorities and obliged to sue for a costly pardon. And his parishioners did not, for the moment, get the security they needed.

For those who were unable to buy their way out of trouble, the only option was to help the enemy or even join them. The story of one Norman gentleman from this same frontier area demonstrates how hazardous this could be. Gilet de Lointren had served as a man-at-arms in Armagnac garrisons from the very beginning of the English invasion. In 1422 he was captured by the Damville garrison and held prisoner for seven months until he raised a ransom of 81 écus (£5906). On his release he went to Senonches, serving six months there before joining five comrades who ‘went to seek adventures in the land of Normandy, as men-at-arms are accustomed to do’.

When he was captured by the English at Verneuil Lointren’s ransom was again set at 81 écus but the men at Damville had already taken everything he had. After six months’ captivity, when it became clear he could not raise the money and would otherwise die in prison, he agreed to change allegiance and serve one of the four men who had shared the rights to his ransom. Eight days later Lointren was captured by the Armagnacs at Nogent-le-Rotrou and, since his masters at Verneuil would not contribute to his ransom, he reverted to his former allegiance and returned to Senonches. Captured again, this time by the English at Beaumesnil, he was given a safe-conduct allowing him to raise a ransom of 40 écus (£2917) at Senonches, only to be taken prisoner for a fifth time as he made his way back with the money. His captors were from Verneuil, recognised him and brought him before the bailli, who condemned him to death. Before the sentence could be carried out there was an extraordinary turn of events. A fifteen-year-old girl from Verneuil, ‘a virgin and of good reputation’, sought an audience with the captain of the garrison, Thomas, lord Scales, and, with her family’s approval, offered to marry Lointren. Scales granted her request, returning Lointren to prison only until his pardon could be obtained. The idea that marriage was a suitable alternative to execution seems to have been peculiarly French: in 1430 a ‘very handsome’ twenty-four-year-old brigand was actually on the scaffold in Paris when another young girl ‘boldly came forward and asked for him’; she got him too, and married him, thus saving his life.

Lointren’s story was remarkable for the number of times he was taken prisoner and the fairy-tale ending, but otherwise it was by no means unusual. For those living within striking distance of Armagnac strongholds or on the frontiers, where the fortunes of war meant that castles frequently changed hands, some sort of accommodation with the enemy was a necessity. For most of them, fear, poverty and the simple desire for a quiet life were far more potent than political conviction in deciding an allegiance that was as pragmatic as it was ephemeral.

Bedford was aware that his best chance of preserving his brother’s legacy and making the English occupation permanent was to provide security and justice for all. In December 1423 the estates-general, which was then in session at Caen, complained that civilians in Normandy could not ‘safely live, trade, work or keep that which is their own’ because of the ‘excesses, abuses, crimes and wrong-doings’ daily perpetrated by the military. Bedford responded immediately by issuing a series of reforming ordinances which, by addressing specific issues, provide a damning indictment of the behaviour of English soldiers.

The ordinances drew together into a single document nearly all the measures which had been issued over the years to control the worst excesses of the soldiery. The most important innovation was that captains were prohibited from interfering directly or indirectly in matters of justice: their sphere of jurisdiction was limited to the purely military, distributing gains of war and dealing with discipline within the garrison. They, and all other soldiers, were strictly enjoined to obey the civilian officers of justice, especially the baill-is, ‘the principal chiefs of justice’ under Bedford himself.

In response to many complaints that captains, ‘French as well as English’, were levying appâtis, Bedford reiterated what had been standard English practice since the beginning of the invasion: nothing whatever was to be taken without due payment and tolls levied on travellers entering towns or castles or crossing bridges, or on boats, carts and horses carrying merchandise, were declared illegal. Anyone who seized civilians for ransom on the pretext that they were ‘Armagnacs or brigands’ was to be punished according to the criminal law. And because some soldiers were pillaging and robbing outside their garrisons, all were ordered to report to their captains within fifteen days and prohibited from living anywhere except within the garrison. All knights and esquires were to be suitably armed and mounted, in readiness for campaigns against brigands, traitors and the enemy.

One clause stands out because it was not strictly concerned with military matters, though it reflects a genuine concern. We understand, Bedford declared, that some of our subjects, ‘English as well as Normans and others’, when speaking of ‘our enemies, rebels, traitors and adversaries who are known as Armagnacs’ or of ‘he who calls himself the dauphin’, refer to them as ‘French’ and ‘the king’. This was now forbidden and anyone who continued to do so, in speech or writing, was to be severely punished, a first offence meriting a fine of 10l.t. (£583) for noblemen or 100 sous (£292) for non-nobles, rising to ten times those amounts or, if the offender was unable to pay, ‘the tongue pierced or the forehead branded’ for a second offence, and criminal prosecution and confiscation of all goods for a third.

The ordinances were to be published ‘at the sound of the trumpet’ in the usual way of proclamations, and all captains, baill-is and their lieutenants were to swear to uphold them. Finally, in a gesture of his determination to deal with the problems caused by indiscipline among his own men, Bedford publicly set his seal to the ordinances in the presence of the estates-general.

These measures were not to be a dead letter but to be enforced by some judicious new appointments. Thomas, lord Scales, was made lieutenant of the regent and captain-general of the Seine towns and Alençon: with twenty men-at-arms and sixty archers he would patrol the Seine between Rouen and Paris to prevent incursions by Armagnacs and brigands. John Fastolf was appointed governor of the triangle south of the Seine between Pont-de-l’Arche, Caen and Alençon, with authority to receive all manner of complaints, punish crimes, execute royal orders, resist the enemy and suppress brigandage. And in April 1424 ‘prudent and powerful knights’ were sent to certain bailliages ‘to ride in arms . . . in order to expel and extirpate the enemies, brigands, and pillagers therein, and to maintain the king’s subjects in peace and tranquillity’. Having reimposed internal discipline and order, Bedford was now in a position to concentrate on his strategy for the defence of his nephew’s realm.