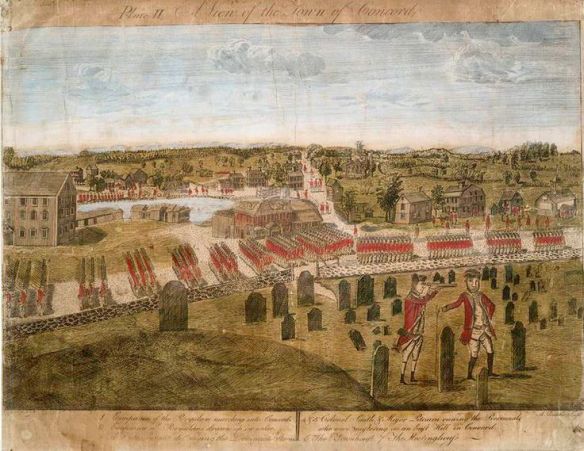

In an engraving by Amos Doolittle, British Major John Pitcairn and Col. Francis Smith survey Concord from a hill in the town cemetery.

After reaching Concord, the Redcoats found themselves surrounded by thousands of armed and angry militia. The march back to Boston, 20 miles away, became a fierce, running battle all through the day. From behind trees, houses, and stone walls, militiamen fired at the troops, who burned houses along the way and often counterattacked.

General Gage had all along been making preparations to use military force against the colonists. He had long since requested additional troops, and during the summer of 1774, with the First Congress looming, he had deployed regiments from Halifax and New York to Boston. At that juncture, Gage may have acted more from hope that his steps would induce the colonists to back down, but after Congress embraced the Suffolk Resolves, he expected war. He began to fortify Boston, digging trenches and gun emplacements, and exercising his men. But Gage was not going to start the war. He was a soldier. He awaited orders, knowing they would come and certain they would direct him to use force. In the meantime, he assembled a network of spies and sent out reconnaissance parties to learn as much as possible about the country surrounding Boston.

Numerous incidents occurred between soldiers and civilians in the city during that winter—one altercation ended with several soldiers tarring and feathering a citizen—but Gage miraculously defused each episode before serious trouble resulted. Nevertheless, Gage came close to igniting the powder keg on February 26 when he sent to Salem 240 regulars under Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Leslie. They were on a mission to seize eight cannon that British intelligence learned had been sent from Europe to the coastal town. Warned that the regulars were coming, a tense standoff took place when the redcoats were greeted (surrounded, in fact) by local militiamen who had been joined by Marblehead militiamen and minutemen from as far as twenty-five miles away. Either because he was outnumbered or had orders not to fire the first shot, Leslie ultimately marched his men to their ship and sailed empty-handed back to Boston.

Six weeks later the inevitable occurred. On April 14 the HMS Nautilus arrived in Boston with Dartmouth’s orders to use force, drafted more than seventy-five days earlier. Gage was not surprised. He in fact had already prepared plans to destroy a rebel arsenal in Concord. He had considered other arms depots, but settled on Concord. Assuming that the countryside would be alerted and that minutemen would descend on Concord to save the ordnance, Gage knew that speed would be crucial to his success. Concord was only twenty miles from Boston, and a spy in the village had passed on information about the location of stockpiles of cannons, mortars, tents, lead balls, medicine, linen, rum, grain, vegetables, and salt fish in and about the town. Gage’s intelligence had additionally reported that Samuel Adams and John Hancock were in Lexington, which the British strike force would pass through en route to Concord, and Dartmouth had ordered the arrest of the leading rebels. Expecting the operation to proceed under a cloak of secrecy, Gage was confident that he could rapidly get his men to Concord and back to Boston. Immediately after the Nautilus docked in Boston Harbor, Gage set April 19 as the date for his lightning strike.

Gage’s force could march across Boston Neck to Roxbury, skirting the Back Bay before turning north and heading through Cambridge toward Lexington and Concord. Or, the regulars might proceed to the Charles River, only a few blocks from their barracks, where the Royal Navy would be waiting with longboats to convey them to the northern shore. The latter option was thought to be the speedier of the two, and it was the one that Gage fixed on.

Unfortunately for General Gage, he was not alone in using spies. The rebels had their own surveillance network, and through an array of clues—and loose lips—they learned when and where the regulars were going, though not which of the two routes Gage had chosen. But they posted Paul Revere in Charlestown and contrived a simple system of signal lights. Lanterns were to be placed in the belfry of Christ Church (also called North Church), the meetinghouse with the tallest steeple in Boston. If one lantern was hung, the regulars were taking the land route via Roxbury; two lanterns would indicate the soldiers were being rowed across the Charles. It was a clear night. Revere saw two lanterns. Not long after the British soldiers had moved out of their barracks, Revere set out on his most famous ride, spurring on Brown Beauty, reputedly the fastest horse about, to alert Hancock and Adams—who were indeed in Lexington—and the militiamen in both that village and Concord. Others riders also mounted up and sped away along other routes to sound the alarm in towns throughout the hinterland.

Gage had dispatched a formidable force of more than nine hundred men—some infantrymen and some grenadiers, the elite of the British army. Filing out of their quarters about ten P.M., the soldiers had been ordered to walk in small parties toward the river, the better for muffling noise and not arousing the suspicions of any Bostonians still awake at such a late hour. All went well until the regulars reached the Charles River. The navy had sent out too few boats. More had to be found. Four hours were lost. It was nearly ten A.M. before the soldiers completed the crossing of the river and started again on their march, slogging along roads made soft from spring rains, past silent fields and dark trees that had stood stark and bare since late in the previous autumn.

Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight and the alarm bell began to ring its tidings of impending danger. Hancock and Adams tarried until nearly dawn, but ultimately fled to the safety of Woburn, northwest of Lexington. Revere, meanwhile, had set off from Lexington for Concord. He never made it. He was captured by a British patrol. Though released after a brief time in custody, his role of spreading the warning on this historic night was over. Dr. Samuel Prescott, a Concord physician who had been visiting his fiancé in Lexington, carried the news back to his village that the redcoats were coming.

The regulars reached Lexington around four thirty. In the first orange streaks of daybreak, they could see some sixty militiamen arrayed on Lexington Common. It is a mystery why the commander of Lexington’s militia, Captain John Parker, a tall, forty-six-year-old farmer-mechanic who had fought in several engagements in the Seven Years’ War, had not marched his men to Concord to join with other colonists to defend the arsenal. Parker may have kept his men in town to protect the inexplicably dawdling Hancock and Adams, though it is more likely that he and his men had remained in Lexington in the hope of defending their families. It is also puzzling why only some 40 percent of Lexington’s militia of 144 men had turned out and were posted on the common when the redcoats arrived. Gut-wrenching fear probably kept most away. After all, the militiamen were not hardened soldiers. Until a few hours before, they had been farmers working their fields or tradesmen toiling at their workbench. Aside from Captain Parker, few, if any, had experienced combat. Standing up to formidable, well-equipped British regulars not only was a daunting prospect, but it was also illegal, and no one on Lexington Common on that chilly spring morning could have known what lay ahead in America’s relations with Great Britain.

Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, whom Gage had put in command of the operation, detached six companies totaling 238 men to clear the village green. He gave the assignment to Major John Pitcairn of the Royal Marines. As the regulars advanced, Captain Parker, anxious and uncertain, in all likelihood not feeling very brave but trying to stand tall in his soiled and well-worn daily work apparel, supposedly told his men: “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon. But if they want to have a war let it begin here.” Pitcairn, immaculately turned out in his gaudy, impeccably tailored red uniform, rode to within a few feet of the citizen-soldiers and in the curt, biting manner and tone customarily used when ordering about cowed subordinates, brusquely bawled a command: “Lay down your arms, you damned rebels.” Parker had no wish to defy the British officer, much less to order his men to fire on the King’s soldiers. Had he done so, Parker would have been taken into custody and charged with a capital crime. Parker ordered his men to step aside. He did not direct them to surrender their arms. None did so.

At this moment, already fraught with unbelievable tension, someone squeezed off a shot. Perhaps a militiaman fired; maybe it was a soldier. Later, some said they thought the shot was fired by someone hiding behind a nearby stone wall. No one then or later knew for sure who had fired the first shot of the Revolutionary War, or whether the gun had been discharged deliberately or by accident.

What was clear was that once the gunshot rang out, a volley of shots was fired into the ranks of the militiamen. Jitters may have led some redcoats to fire, but others deliberately charged toward the citizen-soldiers, the faint light of sunrise gleaming off their shiny bayonets. It took only a minute or so for the officers to restore order, but by then eight colonists were dead and nine others had been wounded. Two regulars had been shot, one in the hand, one in the leg.

Though speed was imperative, a considerable period passed before the regulars resumed their march to Concord, six miles on down the road. Much of that time was squandered in the futile search for Adams and Hancock. As it was apparent that the element of surprise had long since been lost, several officers who suspected rough going ahead urged Colonel Smith to return to Boston. He refused. Orders were orders. But he sent to Gage a request for reinforcements. The regulars reached Concord in mid-morning, some twelve hours after setting out from their barracks in Boston.

The regulars entered Concord without incident. The town’s militia had long since been called out, assembling on their training ground across the Concord River, nearly a half mile north of the heart of the village. Outnumbered nearly three to one, they were in no position to offer resistance. Besides, their commander, Colonel James Barrett, a sixty-five-year-old miller who wore his leather apron this day as he commanded his troops, was no more eager than Captain Parker to order his men to fire on British regulars. Throughout much of the morning, the impatient militiamen remained at a distance, leaving the redcoats to work unhindered under a bright spring sun. But as the soldiers toiled industriously to destroy powder and ordnance in the arsenals, minutemen continued to arrive. As the size of the colonial force swelled, many of the militiamen implored Barrett to act. Barrett held firm until around eleven A.M., when it not only became apparent that his force was probably larger than that of the enemy and when a column of white smoke was spotted rising above the town. Although the regulars were only burning wooden gun carriages, the militiamen feared that the village had been torched. At last, Barrett ordered his men to advance toward the center of Concord.

As they approached the North Bridge, which spanned the gently flowing river, the militiamen saw 115 British infantry posted on the other side. The regulars were scattered and relaxing. On spotting the approaching rebels, however, the British soldiers hurriedly assembled at the foot of the bridge. If the Americans were to reach the center of the village, they would have to fight their way through the king’s soldiers. Barrett ordered his men to advance. Men on both sides were anxious and excited. Both Barrett and the British commander called on those on the opposite side to disperse. No one backed off. Suddenly, a shot was fired. It came from within the British ranks—again, whether by accident or design know one ever knew. In an instant, the nervous redcoat commander ordered his men to fire. Colonial citizen-soldiers began to fall. Only then did Barrett give the order to fire. Twelve regulars were hit, three fatally. Badly outnumbered, the redcoats broke and ran. The militiamen did not pursue them. Having at last done something, and ascertained as well that Concord was not burning, they retreated to their training ground.

By then, Colonel Smith had done all the damage in Concord that was possible, and he shortly ordered his force to begin the trek back to Boston. They set off down what to that day had always been known to Bostonians as the Concord Road. After April 19, 1775, it would be called “Battle Road.” For Smith and his exhausted men—already that day they had marched twenty miles and labored in Concord for a couple of hours under a warm sun —their ordeal was just beginning.

By the time the redcoats began their return march, more than a thousand American militiamen had gathered in Concord. Their numbers grew throughout the afternoon, eventually reaching about 3,600. The colonial force fanned out with febrile intensity, taking positions down Battle Road. Men hid behind stone fences, unpainted barns, leafless trees, and haystacks. Smith sent out flanking parties to root out the militiamen, but he had too few men to do an adequate job. It was a bloodbath. Every few minutes during the fourteen-mile march to Lexington, the redcoats ran into another ambush, though sometimes the militia stood and fought. Not a few of the regulars were surprised by how well the rebels were led and by the valor of the citizen-soldiers. The militiamen were not an “irregular mob,” one British officer accurately remarked. He thought they must have been commanded by officers who had learned the art of war while fighting the French and Indians. “They have men amongst them who know very well what they are about,” he said of the colonial force. The militiamen had performed well under fire, testimony to their leadership, days spent on the drill field during recent months, daring born of the knowledge of the enemy’s vulnerability, conviction bred by rage toward Great Britain, and understanding that were indeed fighting to protect nearby loved ones.

At times, it seemed that every redcoat would be a casualty before the force could reach Boston, and that might have been the outcome of the bloody day had these frightened soldiers of the king not been joined in Lexington by the reinforcements that Smith had called for at daybreak. Around seven A.M. Gage had ordered a brigade under Lord Hugh Percy to march for Lexington. Impeded by one thing or another, the first units in Percy’s force of more than one thousand men did not set off until about two hours later; others began their march throughout the morning. All the men in Percy’s brigade had finally reached Lexington in mid-afternoon, only shortly before the battered, retreating regulars from Concord also arrived. The British force now totaled roughly 1,800 men.

The presence of a larger enemy force notwithstanding, the militia persisted in fighting, and some of the hottest action of the day occurred late that afternoon. The Americans suffered heavy losses at Menotomy, about halfway between Lexington and Boston, losing twenty-five killed and nine wounded; the regulars lost forty dead and eighty wounded in the brawl at Menotomy. Further down the road, at Cambridge, the fighting was no less intense, for several regiments of militia from Cambridge and Brookline joined their comrades. Faced with somehow getting across the wide Charles River in the face of growing numbers of the enemy—an unlikely prospect—Percy changed his plans on the spot. He abruptly ordered his men to march eastward, hopeful that with his artillery he could fashion a defense perimeter in the hilly terrain of Charlestown. That might permit him to hold off the militiamen until the rapidly approaching night came over the region, and by the next morning’s dawn he could be reinforced and protected by the heavy guns of the Royal Navy. The regulars barely made it to safety. Fresh units of militia from Marblehead and Salem were streaming in to join the fight. Had they been thrown into the fray, it appears likely that the entirety of the two forces that Gage had dispatched during that blood-stained day would have been destroyed. But the commander of those troops, Colonel Timothy Pickering, a lukewarm rebel who yearned for a negotiated solution to the Anglo-American breach, withheld his men. The redcoats slipped through. As darkness closed in, the regulars took up positions at a place that the colonists knew as Bunker Hill. Percy and his men were safe for the time being.

This nightmarish day for the proud British army had at last drawn to a close. Later that night, Gage received the appalling butcher’s bill for the day of fighting. To his horror, Gage learned that 65 of his men were dead and 207 had been wounded, the equivalent of nearly one-third of the initial force he had dispatched and roughly 15 percent of all the men sent out that day were casualties.

Americans bled as well. Ninety-four militiamen from twenty-three towns were casualties, including fifty who were known to have died. In addition to the colonial soldiers, civilians also perished when regulars stormed houses along Battle Road in search of ambushers—civilian and militia—whose firing “galled us exceedingly,” in the words of a regular. Afterward, a militiaman who entered a home found carnage beyond belief. The dead were everywhere and the “Blud was half over [my] shoes,” he said.

Years later, Captain Levi Preston of Danvers was asked why he had risked his life in fighting the regulars that day. Was it because of the Stamp Act? No. The Tea Act? No, again. Was it from reading Locke, Trenchard, and Gordon. “I never heard of these men,” he responded. Then why did you fight? He answered, “[W]hat we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”