STRICTURES ON A PAMPHLET, ENTITLED, A “FRIENDLY ADDRESS TO ALL REASONABLE AMERICANS, ON THE SUBJECT OF OUR POLITICAL CONFUSIONS.” ADDRESSED TO THE PEOPLE OF AMERICA. Charles Lee.

There were colonists who believed that the mother country would back down in the face of the resolution and unity exhibited by the Continental Congress, and some hoped the appeal to the monarch would lead him to intercede, pointing the way to an accommodation. Few were so sanguine, however, and the colonists prepared for the worst. Long before Congress adjourned, Massachusetts was readying its militia. The colony’s Provincial Congress directed each town to organize and regularly train its militia, and as speed would be essential in responding to a threat by the British army, it further stipulated that “one-third of the men of their respective towns, between sixteen and sixty years of age, be ready to act at a minute’s warning.” These men would come to be known as “minutemen.” In the other colonies, militia training—or at least some degree of organizing—followed the Continental Congress’s “earnest” admonition that in each province “a Militia be forthwith appointed and well disciplined.” By early 1775, militiamen were training on muddy drill fields in Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Maryland, South Carolina, and Virginia. The latter also created companies of riflemen. They were to consist of those who could “procure Riphel Guns,” were capable marksmen, and were distinguished from other militiamen in that they were to wear “painted Hunting-Shirts and Indian Boots.” Connecticut, which had ordered three days of training each month for its militiamen, also commissioned two independent, or volunteer, companies. Independent companies similarly sprang up in several counties and towns in Virginia, including one in Alexandria that George Washington helped drill and outfit. Virginia and Massachusetts also began producing gunpowder, and some colonies looked into the possibility of acquiring ordinance and munitions from western Europe.

While some men drilled, others sat on the Continental Association committees that Congress had ordered into being to enforce the trade boycotts. Hundreds of committees sprang up in the weeks following Congress’s adjournment; twenty-eight were up and running in Connecticut within two months. For the most part, they variously styled themselves as committees of observation, inspection, or safety, though some called themselves “committees for the detection of conspiracy.” Several colonies created large committees consisting of dozens of members, a step deliberately taken to deepen support for the insurgency. New Jersey and Pennsylvania both had more than five hundred Association committeemen, and some three thousand manned the approximately three hundred committees that came into being in the four New England colonies. Boston’s committee consisted of sixty-three members, including representatives from the Loyal Nine and assorted caucuses.

The Association committees acted with such zeal that the value of British imports during 1775 was just 5 percent of that of the previous year. Taking to heart Congress’s instructions to “observe the conduct” of the citizenry, many committees searched for enemies of the American cause, hoping to identify them through the use of loyalty oaths. Those who refused to sign the oaths were considered Loyalists or Tories. They were placed under surveillance in some locales, disarmed in others, jailed in rare instances, not infrequently harassed and threatened, and here and there “ordered to depart.” Joseph Galloway, now retired, savaged the committeemen as being “drunk with the power they had usurped” and said they “aimed at a general revolution.”

The Association committees were a vital stage on the road to revolution. As historian T. H. Breen has observed, they fostered the “sobering lesson … that the people were ultimately accountable for the common good.” In addition, as most committeemen had never before held power, each had to know that his days as a suddenly influential local figure would come to an end the moment the American insurgency ended. Some were radicalized through their service on committees, while at the same moment the committees—bodies in which power flowed up from the people—provided a legitimacy to the insurgency. Whether by accident or design, Congress’s creation of the Association put in place a structure that nourished intemperate feelings toward the mother country. Within six months of the meeting of the Continental Congress, it was apparent that in much of the country the populace harbored a far more radical outlook than had most of the congressional delegates and that the citizenry was in control of local government throughout America.

Other changes were apparent as well. Shortly before Congress adjourned, the annual October assembly elections in Pennsylvania swept anti-British representatives into control of the legislature. The new majority dumped Galloway from the speakership that he had held for years, immediately added John Dickinson to the province’s delegation in Congress, and ultimately approved the steps Congress had taken. Refusing to concede defeat, Galloway made one final effort to prevent a war that he feared would be catastrophic. He and Governor John Penn drafted a petition to the king. However, whereas Galloway once had been assured of having his way in the Pennsylvania assembly, that no longer was the case. Galloway’s once subservient assembly repudiated the appeal to the monarch by a vote of 22–15.

In New York, where the port city was heavily dependent on British trade, much of the elite feared a rupture with the mother country, anxiety that was also widespread among those who held power throughout the hinterland. During that fall and winter, only three of New York’s thirteen counties adhered to the Continental Association. What is more, New York’s colonial assembly refused to endorse the actions taken by Congress, balked at electing delegates to a second intercolonial congress that was to meet in May if necessary, and adopted a servile appeal to the king similar to the one that Galloway had sought in Pennsylvania. In the spring, however, more radical New Yorkers—acting through an extralegal Committee of sixty—responded as Philadelphia’s radicals had a year earlier. They bypassed the assembly and held elections for a provincial convention. The colonial assembly last met on April 3, 1775, about the time that the provincial convention met and elected delegates to the next congress.

During this period, the final flurry of peacetime pamphleteering occurred. A bevy of Tories assailed Congress and were in turn answered by Whigs. Vitriol flowed, but little new light was shed on Anglo-American differences, and it is unlikely that many minds were changed. As was often true of pamphleteering, readership was probably small, and in Massachusetts the turgid, legalistic essays of John Adams, who wrote as “Novanglus,” and Daniel Leonard, a conservative Taunton lawyer who used the pen name “Massachusettensis,” must have assured a limited audience. In New York, Alexander Hamilton defended Congress, calling those who assailed it “bad men” with “mad imaginations” who engaged in “sophistry” to “dupe” and “dazzle” the American public. Hamilton’s tracts were less sophisticated but more readable than Adams’s, which was all the more remarkable considering that the New Yorker was a nineteen-year-old college student. Remarkably, too, Hamilton served up something novel in the literature of the American insurgency to this point. He may have been the first in print in America to maintain that Britain could not win a war with the colonists. He predicted not only that France and Spain would assist the colonists, but Hamilton also envisioned that by using what were called Fabian tactics, America could prevent a British victory. The colonists could “evade a pitched battle” and instead “harass and exhaust the [British] soldiery.” Attrition suffered by the superior redcoat army would eventually force Britain’s leaders to abandon the war.

Galloway wrote the pamphlet that gained the most notoriety. In A Candid Examination of the Mutual Claims of Great Britain and the Colonies, he broke Congress’s code of silence, revealing the terms of his plan of union and its narrow defeat by those who favored “measures of independence and sedition … to those of harmony and liberty.” Virtually alone among the pamphleteers, Galloway also offered more than the vilification of his political enemies and the monotonous rehashing of familiar issues. His was a thoughtful essay on the need for a strong central government both within the empire and within America. As historian Merrill Jensen observed, Galloway “was concerned with the same problem and used many of the same arguments” that were employed by the authors of The Federalist Papers more than a decade later. For Galloway, however, his essay had calamitous personal consequences. His betrayal of congressional secrets resulted in death threats. Tired and frightened, he retreated to the safety of Trevose, his estate well north of Philadelphia, and when hostilities erupted, he quit the assembly in which he had sat for two decades, unwilling to hold office in a colony that was at war with the mother country.

Perhaps the pamphlet that came closest to expressing the outlook of most Americans—more so than the steps taken by the compromise-driven Congress—was authored by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson penned his essay in the summer of 1774 to instruct Virginia’s delegation to the Continental Congress, taking the trouble in large measure because he badly wished to be included among the delegates. Illness prevented him from attending the Virginia Convention that selected the congressmen, and Jefferson was not included in the delegation. But several members of the convention saw to the publication of what he had written, and at year’s end it appeared in print as A Summary View of the Rights of British America.

Jefferson’s handiwork stood out for several reasons. It was composed in a crisp, lucid, and flowing style that made it one of the more readable pamphlets. In addition, he took issue with the nearly universal belief in England (and among Tories) that the mother country had nurtured the colonists from infancy. In Jefferson’s version, several generations of Virginians, with next to no help from England, had repeatedly fought and defeated the Indians, opening one new western frontier after another. America was made by American colonists, he insisted. He denied that Parliament had any authority over the colonies, including the regulation of trade or restraints on manufacturing. Americans, he said, had a “natural right” to “a free trade with all parts of the world”; he labeled bans on manufacturing “instance[s] of despotism.” The most cogent portion of his essay was his charge that the monarch was complicit in Britain’s iniquitous designs on America. Abandoning the customary servile language the colonists used when writing of the monarch, Jefferson alleged that the king had strayed beyond his legitimate executive role to cooperate with Parliament in its “many unwarrantable encroachments and usurpations,” especially its “wanton exercise of … power” in sending troops to the colonies in peacetime and disallowing legislation enacted by colonial assemblies. He excoriated George III both for having ignored the colonists’ petitions for redress and for his blind indifference toward American interests, including the Crown’s refusal to permit the colonists to migrate across the Appalachians. The monarch’s behavior, Jefferson wrote, threatened to leave his reputation as “a blot in the page of history.”

No one knows how many colonists read Jefferson’s pamphlet, though large numbers of congressmen and provincial assemblymen probably perused it, and most may have read it after hostilities began. Timing is everything in politics, and for many readers Jefferson’s powerful language, captivating story of American prowess, and direct confrontation with the monarchy stood out a crucial moment.

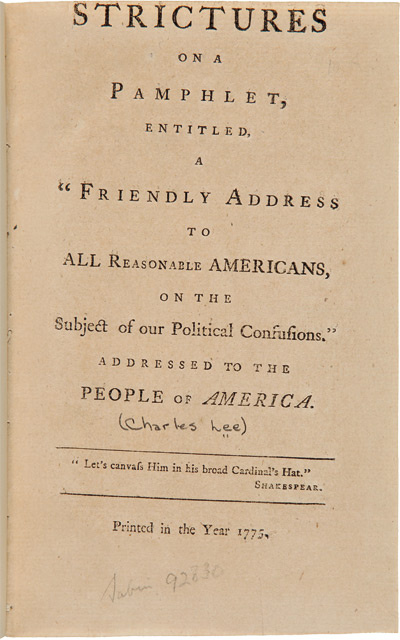

The pamphlet that may have reached the largest audience at this juncture was Strictures on “A Friendly Address to all Reasonable Americans.” It was written by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Lee, a native of Great Britain and for two decades an officer in the British army. Lee had resigned his commission and moved to Virginia in the early 1770s. Spurred by the likelihood of hostilities, his tract—which appeared a few months after Hamilton’s—contended that the colonists could win a war against the mother country. British soldiers were overrated and often led by incapable officers, he asserted, adding that the colonists could quickly raise and train a viable army. Furthermore, Americans would have a psychological advantage. They would be fighting for something tangible and invaluable: their liberty.

As wintry March gave way to April’s softer spring weather in 1775, nearly six months had elapsed since the adjournment of Congress. America and the colonists had changed during that period, and the political changes in the year since news arrived of the Intolerable Acts had been especially breathtaking. Royal authority had disappeared throughout much of the American landscape, the importation and sale of British goods had ended, and citizen-soldiers were training. A transformation appears to have occurred as well in the thinking of many colonists. The emphatic good will, even deep affection, that once had existed toward the mother country had been replaced by a sour mistrust that often bordered on loathing. Whether or not they fully understood it, the colonists were coming to see themselves more as Americans than as British-Americans, and increasing numbers were, like Jefferson in A Summary View, no longer willing to acquiesce in “160,000 electors in the island of Great Britain … [giving] law to four [sic] millions in the states of America.” Most may not yet have come to long for American independence, but the vast majority desired greater independence from the sway of the mother country and were willing to fight for it. Once again, it may have been Jefferson who best captured the spirit of the moment. The colonists, he had written, felt that submission to what they saw as tyranny was “not an American art.”